Synchronicity

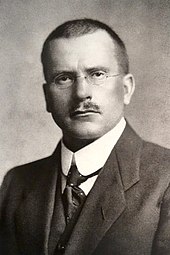

Synchronicity (German: Synchronizität) is a concept introduced by analytical psychiatrist Carl Jung to describe events that coincide in time and appear meaningfully related, yet lack a discoverable causal connection.

[2][3] Jung developed the theory as a hypothetical noncausal principle serving as the intersubjective or philosophically objective connection between these seemingly meaningful coincidences.

After coining the term in the late 1920s[4] Jung developed the concept with physicist Wolfgang Pauli through correspondence and in their 1952 work The Interpretation of Nature and the Psyche.

Jung stated that synchronicity events are chance occurrences from a statistical point of view, but meaningful in that they may seem to validate paranormal ideas.

These explain coincidences such as synchronicity experiences as chance events which have been misinterpreted by confirmation biases, spurious correlations, or underestimated probability.

Jung met Wilhelm in Darmstadt, Germany where Hermann von Keyserling hosted Gesellschaft für Freie Philosophie.

But he knew the entire literature and could therefore fill in the gaps which had been outside my competence.Jung coined the term synchronicity as part of a lecture in May 1930,[14] or as early as 1928,[4] at first for use in discussing Chinese religious and philosophical concepts.

By selecting a passage according to the traditional chance operations such as tossing coins and counting out yarrow stalks, the text is supposed to give insights into a person's inner states.

]As with Paul Kammerer's theory of seriality developed in the late 1910s, Jung looked to hidden structures of nature for an explanation of coincidences.

[18] It was not until a 1951 Eranos conference lecture, after having gradually developed the concept for over two decades, that Jung gave his first major outline of synchronicity.

[18] The Pauli–Jung conjecture is a collaboration in metatheory between physicist Wolfgang Pauli and analytical psychologist Carl Jung, centered on the concept of synchronicity.

[9][31][32] Jung and Pauli thereby "offered the radical and brilliant idea that the currency of these correlations is not (quantitative) statistics, as in quantum physics, but (qualitative) meaning".

The notion of synchronicity shares with modern physics the idea that under certain conditions, the laws governing the interactions of space and time can no longer be understood according to the principle of causality.

[38][39] Jung's use of the concept in arguing for the existence of paranormal phenomena has been widely considered pseudoscientific by modern scientific scepticism.

Because of this quality of simultaneity, I have picked on the term "synchronicity" to designate a hypothetical factor equal in rank to causality as a principle of explanation.

Indeed, Jung's writings in this area form an excellent general introduction to the whole field of the paranormal.For example, psychologists were significantly more likely than both counsellors and psychotherapists to agree that chance coincidence was an explanation for synchronicity, whereas, counsellors and psychotherapists were significantly more likely than psychologists to agree that a need for unconscious material to be expressed could be an explanation for synchronicity experiences in the clinical setting.

Psychologist Fritz Levi, a contemporary of Jung, criticised the theory in his 1952 review, published in the periodical Neue Schweizer Rundschau (New Swiss Observations).

[54]Robert Todd Carroll, author of The Skeptic's Dictionary in 2003, argues that synchronicity experiences are better explained as apophenia—the tendency for humans to find significance or meaning where none exists.

What I have tried to do is pull out and make explicit how physics and mathematics, in the form of probability calculus does explain why such striking and apparently highly improbable events happen.

It was the nearest analogy to a golden scarab that one finds in our latitudes, a scarabaeid beetle, the common rose-chafer (Cetonia aurata), which contrary to its usual habits had evidently felt an urge to get into a dark room at this particular moment.

I should explain that the main reason for this was my patient's animus, which was steeped in Cartesian philosophy and clung so rigidly to its own idea of reality that the efforts of three doctors—I was the third—had not been able to weaken it.

But when the "scarab" came flying in through the window in actual fact, her natural being could burst through the armor of her animus possession and the process of transformation could at last begin to move.

[57]After describing some examples, Jung wrote: "When coincidences pile up in this way, one cannot help being impressed by them—for the greater the number of terms in such a series, or the more unusual its character, the more improbable it becomes.

"[12]: 91 French writer Émile Deschamps claims in his memoirs that, in 1805, he was treated to some plum pudding by a stranger named Monsieur de Fontgibu.

Ten years later, the writer encountered plum pudding on the menu of a Paris restaurant and wanted to order some, but the waiter told him that the last dish had already been served to another customer, who turned out to be de Fontgibu.

[58] In his book Thirty Years That Shook Physics: The Story of Quantum Theory (1966), George Gamow writes about Wolfgang Pauli, who was apparently considered a person particularly associated with synchronicity events.

Pauli wrote that he had gone to visit Bohr and at the time of the mishap in Franck's laboratory his train was stopped for a few minutes at the Göttingen railroad station.

A song from the album, "Synchronicity II", simultaneously describes the story of a man experiencing a mental breakdown and a lurking monster emerging from a Scottish lake.