Chariot racing

Roman and later Byzantine emperors, mistrustful of private organisations as potentially subversive, took control of the teams, especially the Blues and Greens, and appointed officials to manage them.

[2][3] The participants in this race were drawn from leading figures among the Greeks; Diomedes of Argos, the poet Eumelus, the Achaean prince Antilochus, King Menelaus of Sparta, and the hero Meriones.

[12] Pausanias offers several theories regarding the origins of an object named Taraxippus ("Horse-disturber"), an ancient round altar, tomb or Heroon embedded within one of the entrance-ways to the track.

[21] Chariot teams were costly to own and train, and the case of Alcibiades shows that for the wealthy, this was an effective and honourable form of self-publicity; they were not expected to risk their own lives.

In the classical era, other great festivals emerged in Asia Minor, Magna Graecia, and the mainland, providing the opportunity for cities to compete for honour and renown, and for their athletes to gain fame and riches.

While the entertainment value of chariot races tended to overshadow any sacred purpose, in late antiquity the Church Fathers still saw them as a traditional "pagan" practice and advised Christians not to participate.

[53][54] When the chariots were ready the editor, usually a high-status magistrate, dropped a white cloth;[55] all the gates sprang open at the same time, allowing a fair start for all participants.

It eventually became very elaborate, with temples, statues and obelisks and other forms of art, though the addition of these multiple adornments obstructed the view of spectators on the trackside's lower seats, which were close to the action.

Men and women were supposed to occupy segregated seating but the "law of the place" allowed most to sit together, which for the Augustan poet Ovid presented opportunities for seduction.

[44] The circus was one of few places where the populace could assemble in vast numbers, and exercise the freedom of speech associated with theatre factions and claques, voicing support or criticism of their rulers and each other.

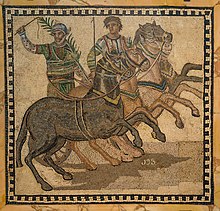

Then they were free to jockey for position, cutting across the paths of their competitors, moving as close to the spina as they could, and whenever possible forcing their opponents to find another, much longer route forwards.

[62][63] A driver who became entangled in a crash risked being trampled or dragged along the track by his own horses; charioteers carried a curved knife (falx) to cut their reins, and wore helmets and other protective gear.

In a previous century, the emperor Domitian had managed to squeeze an extraordinary 100 races into a single afternoon, presumably by drastically lowering the number of laps from the standard 7.

Twenty four races in a single day became the norm, until the slow collapse of Rome's economy in the West, when costs rose, sponsors were lost and racetracks were abandoned.

No contemporary source describes these factions as official, but unlike many unofficial organisations in Rome, they were evidently tolerated as useful and effective rather than feared as secretive and potentially subversive.

[74] By his time, there were four factions; the Reds were dedicated to Mars, the Whites to the Zephyrus, the Greens to Mother Earth or spring, and the Blues to the sky and sea or autumn.

Emperors who took the reins as charioteer, or promoted drivers to elite status or freely mixed with arenarii—as did Caligula, Nero and Elagabalus, for example—were also notoriously "bad" rulers.

Two jurists of the later imperial era, and some modern scholars, argue against the legal status of charioteers as infames, on the grounds that athletic competitions were not mere entertainment but "seemed useful" as honourable displays of Roman strength and virtus.

Slave-charioteers could not lawfully own property, including money, but their masters could pay them regardless, or retain all or some accumulated driving fees and winnings on their behalf, as the price of their eventual manumission.

More usually, some charioteers and supporters tried to enlist supernatural help by covertly burying curse tablets at or near the track, appealing to spirits and deities of the underworld for the success of their favourites or disaster for their opponents; a common practise among Romans of all classes though like all magic, strictly illegal, and punishable by death.

[91][92] Justinian I's reformed legal code specifically prohibits drivers from placing curses on their opponents, and invites their co-operation in bringing offenders before the authorities, rather than acting like assassins or vigilantes.

This not only reiterates a very longstanding prohibition of witchcraft throughout the Empire but confirms a reputation that charioteers had for living at the very edge of the law, for violent thefts, blackmail and bullying as debt collectors on their masters' behalf, and an easy-going criminality that could extend to the murder of opponents and enemies, disguised as rough but rightful justice.

[97][98][99][100] In the eastern provinces, and Constantinople itself, the earliest evidence for colour factions is from AD 315, coincident with the extension of imperial authority into local government and public life.

[103] Semi-permanent alliances of Blues (Βένετοι, Vénetoi) and Greens (Πράσινοι, Prásinoi) overshadowed the Whites (Λευκοὶ, Leukoí) and Reds (Ῥούσιοι, Rhoúsioi).

In the 5th century, the outstanding Byzantine charioteer Porphyrius raced as a "Blue" or a "Green" at various times; he was celebrated by each faction, and by the reigning Emperor, and was honoured with several imperially subsidised monuments on a grand scale in the Hippodrome.

[105] Social discontent and disturbances in Constantinople tended to focus on the Hippodrome, which was not only ideal for racing but by far the largest and most conveniently designed space for mass meetings and their containment.

[107][108] Byzantium's theatre claques, which already had a reputation for well-organised violence, were now identified with the racing factions, and were thought to represent the rowdiest, most uncontrollable elements among the Blues and Greens.

Justin I (r. 518–527) took severe, but apparently indiscriminate, misdirected and ultimately ineffective measures against urban violence after a citizen was murdered in the church of Hagia Sophia.

The Byzantine historian Procopius saw the entire affair as a failure of the Emperor and his authorities to manage their imperial troops and govern their people, and the almost complete lack of a dedicated police force.

[114] The iconoclast emperor Constantine V (r. 741–775) deployed both Green and Blue "rowdies" in his anti-monastic campaigns, staging theatrical shows in which monks and nuns were exposed to public ridicule, abuse and forced marriages.