Brain–computer interface

[1] They are often conceptualized as a human–machine interface that skips the intermediary of moving body parts (e.g. hands or feet), although they also raise the possibility of erasing the distinction between brain and machine.

Although the term had not yet been coined, one of the earliest examples of a working brain-machine interface was the piece Music for Solo Performer (1965) by American composer Alvin Lucier.

Beginning in 2013, DARPA funded BCI technology through the BRAIN initiative, which supported work out of teams including University of Pittsburgh Medical Center,[23] Paradromics,[24] Brown,[25] and Synchron.

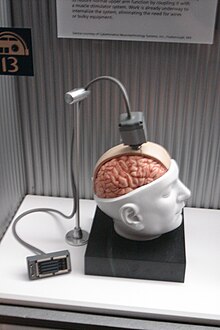

[26] Neuroprosthetics is an area of neuroscience concerned with neural prostheses, that is, using artificial devices to replace the function of impaired nervous systems and brain-related problems, or of sensory or other organs (bladder, diaphragm, etc.).

[31] In 1969 operant conditioning studies by Fetz et al. at the Regional Primate Research Center and Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Washington School of Medicine showed that monkeys could learn to control the deflection of a biofeedback arm with neural activity.

In the 1980s, Georgopoulos at Johns Hopkins University found a mathematical relationship between the electrical responses of single motor cortex neurons in rhesus macaque monkeys and the direction in which they moved their arms.

[35] Duke University professor Miguel Nicolelis advocates using multiple electrodes spread over a greater area of the brain to obtain neuronal signals.

[42][43][44] Andersen's group used recordings of premovement activity from the posterior parietal cortex, including signals created when experimental animals anticipated receiving a reward.

[58] In 2002, Jens Naumann, also blinded in adulthood, became the first in a series of 16 paying patients to receive Dobelle's second generation implant, one of the earliest commercial uses of BCIs.

[61][62] BCIs focusing on motor neuroprosthetics aim to restore movement in individuals with paralysis or provide devices to assist them, such as interfaces with computers or robot arms.

[63] Tetraplegic Matt Nagle became the first person to control an artificial hand using a BCI in 2005 as part of the first nine-month human trial of Cyberkinetics's BrainGate chip-implant.

[65] Research teams led by the BrainGate group and another at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, both in collaborations with the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), demonstrated control of prosthetic limbs with many degrees of freedom using direct connections to arrays of neurons in the motor cortex of tetraplegia patients.

The participant imagined moving his hand to write letters, and the system performed handwriting recognition on electrical signals detected in the motor cortex, utilizing Hidden Markov models and recurrent neural networks.

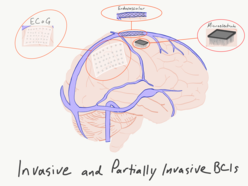

Advances in CMOS technology are pushing and enabling integrated, invasive BCI designs with smaller size, lower power requirements, and higher signal acquisition capabilities.

Yet another concern is that invasive BCIs must be low-power, so as to dissipate less heat to surrounding tissue; at the most basic level more power is traditionally needed to optimize signal-to-noise ratio.

[82][83] As a result, flexible[84][85][86] and tissue-like designs[87][88] have been researched and developed to minimize foreign-body reaction by means of matching the Young's modulus of the electrode closer to that of brain tissue.

[2] Stentrode is a monolithic stent electrode array designed to be delivered via an intravenous catheter under image-guidance to the superior sagittal sinus, in the region which lies adjacent to the motor cortex.

[91] In November 2020, two participants with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis were able to wirelessly control an operating system to text, email, shop, and bank using direct thought using Stentrode,[93] marking the first time a brain-computer interface was implanted via the patient's blood vessels, eliminating the need for brain surgery.

[99] This feature profile and evidence of the high level of control with minimal training requirements shows potential for real world application for people with motor disabilities.

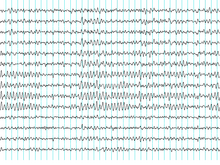

Although EEG-based interfaces are easy to wear and do not require surgery, they have relatively poor spatial resolution and cannot effectively use higher-frequency signals because the skull interferes, dispersing and blurring the electromagnetic waves created by the neurons.

Together with Birbaumer and Jonathan Wolpaw at New York State University they focused on developing technology that would allow users to choose the brain signals they found easiest to operate a BCI, including mu and beta rhythms.

[126] In 2013, comparative tests performed on Android cell phone, tablet, and computer based BCIs, analyzed the power spectrum density of resultant EEG SSVEPs.

For example, Gert Pfurtscheller of Graz University of Technology and colleagues demonstrated a BCI-controlled functional electrical stimulation system to restore upper extremity movements in a person with tetraplegia due to spinal cord injury.

[139] In a widely reported experiment, fMRI allowed two users to play Pong in real-time by altering their haemodynamic response or brain blood flow through biofeedback.

The top performing algorithm from BCI Competition IV in 2022[148] dataset 2 for motor imagery was the Filter Bank Common Spatial Pattern, developed by Ang et al. from A*STAR, Singapore.

[153] On 27 February 2013 Miguel Nicolelis's group at Duke University and IINN-ELS connected the brains of two rats, allowing them to share information, in the first-ever direct brain-to-brain interface.

These include obtaining informed consent from individuals with communication difficulties, the impact on patients' and families' quality of life, health-related side effects, misuse of therapeutic applications, safety risks, and the non-reversible nature of some BCI-induced changes.

Concerns include issues of accountability and responsibility, such as claims that BCI influence overrides free will and control over actions, inaccurate translation of cognitive intentions, personality changes resulting from deep-brain stimulation, and the blurring of the line between human and machine.

[175] Other concerns involve the use of BCIs in advanced interrogation techniques, unauthorized access ("brain hacking"),[176] social stratification through selective enhancement, privacy issues related to mind-reading, tracking and "tagging" systems, and the potential for mind, movement, and emotion control.

[217] In 2016, scientists out of the University of Melbourne published preclinical proof-of-concept data related to a potential brain-computer interface technology platform being developed for patients with paralysis to facilitate control of external devices such as robotic limbs, computers and exoskeletons by translating brain activity.