Antioch

Antioch was founded near the end of the fourth century BC by Seleucus I Nicator, one of Alexander the Great's generals, as one of the tetrapoleis of Seleucis of Syria.

The city also attracts Muslim pilgrims who visit the Habib-i Najjar Mosque, which they believe to contain the tomb of Habib the Carpenter, mentioned in the Surah Yā-Sīn of the Quran.

[16][9] About 6 kilometres (4 miles) west and beyond the suburb Heraclea lay the paradise of Daphne, a park of woods and waters, in the midst of which rose a great temple to the Pythian Apollo, also founded by Seleucus I and enriched with a cult-statue of the god, as Musagetes, by Bryaxis.

It enjoyed a reputation for being "a populous city, full of most erudite men and rich in the most liberal studies",[19] but the only names of distinction in these pursuits during the Seleucid period that have come down to us are Apollophanes, the Stoic, and one Phoebus, a writer on dreams.

The nicknames which they gave to their later kings were Aramaic; and, except Apollo and Daphne, the great divinities of north Syria seem to have remained essentially native, such as the "Persian Artemis" of Meroe and Atargatis of Hierapolis Bambyce.

[18] The epithet "Golden" suggests that the external appearance of Antioch was impressive, but the city needed constant restoration owing to the seismic disturbances to which the district has always been subjected.

[18] The Roman emperors favored the city from the first moments, seeing it as a more suitable capital for the eastern part of the empire than Alexandria could be, because of the isolated position of Egypt.

A circus, other colonnades and great numbers of baths were built, and new aqueducts to supply them bore the names of Caesars, the finest being the work of Hadrian.

Zarmanochegas (Zarmarus) a monk of the Sramana tradition of India, according to Strabo and Dio Cassius, met Nicholas of Damascus in Antioch around 13 AD as part of a Mission to Augustus.

This is somewhat analogous to the manner in which several popes, heads of the Roman Catholic Church remained "Bishop of Rome" even while residing in Avignon, in present-day France, in the fourteenth century.

Further, Julian was surprised and dismayed when at the city's annual feast of Apollo the only Antiochene present was an old priest clutching a goose, showing the decay of paganism in the town.

His enthusiasm for large scale animal sacrifice meant that the soldiers were often to be found gorged on sacrificial meat, making a drunken nuisance of themselves on the streets while Antioch's hungry citizens looked on in disgust.

[37] Julian's successor Valens endowed Antioch with a new forum, including a statue of his brother and co-emperor Valentinian I on a central column, and reopened the great church of Constantine, which stood until the Persian sack in 538, by Chosroes.

The Byzantines were defeated by forces under the generals Shahrbaraz and Shahin Vahmanzadegan at the Battle of Antioch, after which the city fell to the Sassanians, together with much of Syria and eastern Anatolia.

The principal local saint was Simeon Stylites, who lived an extremely ascetic life atop a pillar for 40 years some 65 kilometres (40 miles) east of Antioch.

[43] In 637, during the reign of the Byzantine emperor Heraclius, Antioch was conquered by Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah of the Rashidun Caliphate during the Battle of the Iron Bridge, marking the beginning of Islamic influence in the region.

The city remained an important urban center, with its multicultural population including Christians, Muslims, and Jews living together, although there were periods of tension and conflict.

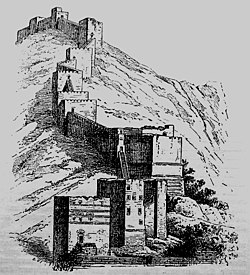

[44] However, since the Umayyad dynasty was unable to penetrate the Anatolian Plateau, Antioch found itself on the frontline of the conflicts between two hostile empires during the next 350 years, so that the city went into a precipitous decline.

Under the Abbasids, closer relations were developed with Byzantium, but it was not until the Fatimids opened up the Mediterranean for shipping from the end of the fourth/tenth century that the affairs of western Europe and the Near East began to interact once again.

[41] As the empire disintegrated rapidly before the Komnenian restoration, Dux of Antioch & Domestic of the Schools of the East Philaretos Brachamios held the city until Suleiman ibn Qutalmish, the emir of Rum, captured it from him in 1084.

In 1107 Bohemond enraged by an earlier defeat, renamed Tancred as the regent of Antioch so he could sail for Europe with the intent of gaining support for an attack against the Greeks.

Immediately after assuming control, Raymond was involved in conflicts with the Byzantine Emperor John II Comnenus who had come south to recover Cilicia from Leo of Armenia, and to reassert his rights over Antioch.

[57] After the fall of Edessa in 1144, many Syriac Orthodox Christians came into the city, spreading the veneration of Mor Barsauma among the local population which resulted in the building of a church to the saint in 1156.

Louis refused to help Antioch defend against the Turks and to lead an expedition against Aleppo, and instead decided to finish his pilgrimage to Jerusalem rather than focus on the military aspect of the Crusades.

[62] One year later, Nur ad-Din Zangi captured Bohemond III but was soon released; however, Harem, Syria, which Raynald had recaptured in 1158, was lost again and the frontier of Antioch was permanently placed west of the Orontes.

Between 1831 and 1840, Antioch was the military headquarters of Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt during the Egyptian occupation of Syria, and served as a model site for the modernizing reforms he wished to institute.

The excavation team failed to find the major buildings they hoped to unearth, including Constantine's Great Octagonal Church or the imperial palace.

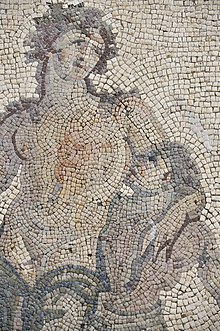

According to William Robertson Smith the Tyche of Antioch was originally a young virgin sacrificed at the time of the founding of the city to ensure its continued prosperity and good fortune.

[86] The northern edge of Antakya has been growing rapidly over recent years, and this construction has begun to expose large portions of the ancient city, which are frequently bulldozed and rarely protected by the local museum.

In April 2016, archaeologists discovered a Greek mosaic showing a skeleton lying down with a wine pitcher and loaf of bread alongside a text that reads: "Be cheerful, enjoy your life", it is reportedly from the third century BC.