Nobility privileges in Poland

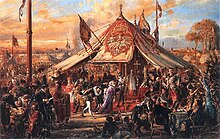

By the end of that period, the szlachta had succeeded in garnering numerous rights, empowering themselves and limiting the powers of the elective Polish monarchy to an extent unprecedented elsewhere in Europe at the time.

[4] Under the terms of this privilege, the king promised not to levy any extraordinary taxes, and to compensate the nobles for any losses they suffered on his behalf while fighting abroad.

This was enshrined in the principle of nullum terrigenam possessionatum capiemus, nisi judicio rationabiliter fuerit convictus, or in short, neminem captivabimus.

[5] Finally, the nobility received important rights with regards to control over the military: levying the pospolite ruszenie, the Polish levée en masse, could not be done without their consent, and service abroad had to be compensated by the king.

[5] The Privilege of Cerkwica, granted in 1454 and confirmed the same year by the Statutes of Nieszawa, required the king to seek the nobles' approval at sejmiks, the local parliaments, when issuing new laws, levying the pospolite ruszenie, or imposing new taxes.

[9] The king, Zygmunt I of Poland, also promised to convene the Sejm every four years,[6] and in either 1518 or 1521 (sources vary) the peasants lost the right to complain to the royal court.

[9][11][12] The Articles, named after King Henryk Walezy (Henry III of France), confirmed numerous previous privileges and introduced new limitations on the monarch.

[2] Anna Pasterak lists 1578, the year in which King Stefan Batory passed the right to deal with appeals into the hands of the nobility, creating the Crown Tribunal, as the date that marks the end of the process of the shaping of the nobles' privileges in Poland.

[9] Robert Bideleux and Ian Jeffries, go even further, listing the year 1611 as the end, pointing out that it was only then that it was confirmed that only nobles were permitted to buy landed estates.

[2] The empowerment of the szlachta and the incremental limitation of monarchic power in Poland can be seen as parallel to the guarantees made to the barons in Magna Carta, the precursor to the parliamentary ideals of Great Britain and, to a lesser extent, the United States, within which modern democracy has evolved.

[2][15] The nobles' political monopoly on power resulted in stifling the development of the towns and cities and hurting the economy, which, coupled with their control over taxation, kept at a very low level, starved the government of income.