Western Front tactics, 1917

1915 1916 1917 1918 Associated articles In 1917, during the First World War, the armies on the Western Front continued to change their fighting methods, due to the consequences of increased firepower, more automatic weapons, decentralisation of authority and the integration of specialised branches, equipment and techniques into the traditional structures of infantry, artillery and cavalry.

Tanks, railways, aircraft, lorries, chemicals, concrete and steel, photography, wireless and advances in medical science increased in importance in all of the armies, as did the influence of the material constraints of geography, climate, demography and economics.

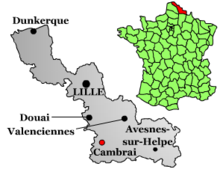

Hindenburg and Ludendorff visited the Western front and held a meeting at Cambrai on 8 September with the army group and other commanders, at which the gravity of the situation in France and the grim prospects for the new year were debated.

These defences were planned with the experience gained on the Somme, which showed a need for much greater defensive depth and many small shallow concrete Mannschafts-Eisenbeton-Unterstände (Mebu shelters), rather than elaborate entrenchments and deep dug-outs, which had become man-traps.

[5] Ludendorff continued to vacillate but in the end, the manpower crisis and the prospect of releasing thirteen divisions by a withdrawal on the Western Front, to the new Siegfriedstellung (Hindenburg line), overcame his desire to avoid the tacit admission of defeat it represented.

The superiority in manpower enjoyed by the Entente and its allies could not be surpassed but Hindenburg and Ludendorff drew on ideas from Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant-Colonel) Max Bauer of the Operations Section at OHL HQ in Mézières, for a further industrial mobilisation, to equip the army for the materialschlacht (battle of equipment/battle of attrition) being inflicted on it in France, which would only intensify in 1917.

Ernst von Wrisberg, Abteilungschef of the kaiserlicher Oberst und Landsknechtsführer (head of the Prussian Ministry of War section responsible for raising new units), had grave doubts about the wisdom of the increase in the expansion of the army but was over-ruled by Ludendorff.

The Battle of the Somme further reduced the German reserve of ammunition and when the infantry was forced out of the front position, the need for Sperrfeuer (barrage fire), to compensate for the lack of obstacles, increased.

Ludendorff's new defensive methods had been controversial; during the Battle of the Somme in 1916 Colonel Fritz von Loßberg (Chief of Staff of the 1st Army) had been able to establish a line of relief divisions (Ablösungsdivisionen), with the reinforcements from Verdun, which began to arrive in greater numbers in September.

[25] Loßberg considered that spontaneous withdrawals would disrupt the counter-attack reserves as they deployed and further deprive battalion and division commanders of the ability to conduct an organised defence, which the dispersal of infantry over a wider area had already made difficult.

The sceptics wanted the Somme practice of fighting in the front line to be retained and authority devolved no further than battalion, so as to maintain organizational coherence, in anticipation of a methodical counter-attack (Gegenangriff) after 24–48 hours, by the relief divisions.

[25] General Ludwig von Falkenhausen, commander of the 6th Army, arranged his infantry in the Arras area according to Loßberg and Hoen's preference for a rigid defence of the front-line, supported by methodical counter-attacks (Gegenangriffe), by the "relief" divisions (Ablösungsdivisionen) on the second or third day.

[30] Using the new defensive system, the 18th Division in the German 1st Army, held an area of the Hindenburg Position with an outpost zone along a ridge near La Vacquerie and a main line of resistance 600 yd (550 m) behind.

General Edmund Allenby, in command of the Third Army proposed to use Corps mounted troops and infantry to press ahead beyond the main body, which was accepted by Haig, since the new dispersed German defensive organisation gave more scope to cavalry.

Behind the lines (defined as the area not subject to German artillery fire) improvements in infrastructure and supply organisation made in 1916, had led to the creation of a Directorate-General of Transportation (10 October 1916) and a Directorate of Roads (1 December) allowing army headquarters to concentrate on operations.

[52] The first days of the British Arras offensive, saw another German defensive debacle similar to that at Verdun on 15 December 1916, despite an analysis of that failure being issued swiftly, which concluded that deep dug-outs in the front line and an absence of reserves for immediate counter-attacks, were the cause of the defeat.

[53] At Arras similarly obsolete defences over-manned by infantry, were devastated by artillery and swiftly overrun, leaving the local reserves with little choice but to try to contain further British advances and wait for the relief divisions, which were too far away to counter-attack.

A memorandum was issued summarising the conference, in which Gough stressed his belief in the need for front-line commanders to use initiative and advance into vacant or lightly occupied ground beyond the objectives laid down, without waiting for orders.

In XIV Corps, divisions were to liaise with 9 Squadron RFC for training and to conduct frequent rehearsals of infantry operations, to give commanders experience in dealing with unexpected occurrences, which were more prevalent in semi-open warfare.

[77] Gough issued another memorandum on 30 June, summarising the plan and referring to the possibility that the attack would move to open warfare after 36 hours, noting that this might take several set-piece battles to achieve.

On 23 July, the division returned to the front line and commenced raiding, to take prisoners and to watch for a local withdrawal, while tunnelling companies prepared large underground chambers, to shelter the attacking infantry before the offensive began.

[c] Eingreif divisions were accommodated 10,000–12,000 yd (5.7–6.8 mi; 9.1–11.0 km) behind the front line and began their advance to assembly areas in the rückwärtiges Kampffeld, ready to intervene in the Grosskampffeld, for den sofortigen Gegenstoß (the instant-immediate counter-thrust).

3" detailed the strong points to be built on captured ground, to accommodate a platoon each, equipment and clothing to conform to Section 31 of SS 135, with an amendment that the battalions on the final objective would carry more ammunition.

Instructions 13–15, between 18 September and the start of the attack, covered late changes, such as reserving the use of telephones to unit commanders and the provision of two wireless tanks, for the south-east corner of Glencorse Wood for local use and as an emergency station for both Australian divisions.

The changes in British tactics meant that they had swiftly established a defence in depth on reverse slopes, protected by standing barrages, in dry, clear, weather with specialist counter-attack reconnaissance aircraft for the observation of German troop movements and improved contact-patrol and ground-attack operations by the RFC.

Concealment (die Leere des Gefechtsfeldes) was emphasised, to protect the divisions from British fire power, by avoiding anything resembling a trench system in favour of dispersal in crater fields.

[151] The RFC continued its development of ground attack operations, with a more systematic organisation of duties and coverage of the battlefield, drawing on the lessons of the Third Battle of Ypres and the pioneering work done during the capture of Hill 70 in August.

Supply dumps, infantry and artillery tracks, dressing stations and water points for 7,000 horses per hour were built, with no increase in movement of lorries by day and no work in forward areas allowed.

In Gruppe Caudry, some of the artillery and mortars arrived too late to be well placed, the attacking infantry lacked time to study the plan and rehearse and some flame throwers had no fuel until the last minute.

[181] In 1919 McPherson wrote that in the aftermath of the battle, "it was plain that the defensive must always contemplate the possibility of having large sections of the front broken, and of having to repair those breaches by considerable counter offensives....", which caused the German command to divert resources into anti-tank defences and end the skimping of artillery and ammunition in some areas to reinforce others.