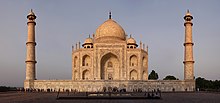

Taj Mahal

The tomb is the centrepiece of a 17-hectare (42-acre) complex, which includes a mosque and a guest house, and is set in formal gardens bounded on three sides by a crenellated wall.

[5][6][7] Abdul Hamid Lahori, in his book from 1636 Padshahnama, refers to the Taj Mahal as rauza-i munawwara (Perso-Arabic: روضه منواره, rawdah-i munawwarah), meaning the illumined or illustrious tomb.

After her death, he avoided royal affairs for a week due to his grief and gave up listening to music and lavish dressing for two years.

Shah Jahan was enamoured by the beauty of the land at the south side of Agra on which a mansion belonging to Raja Jai Singh I stood.

He chose the place for the construction of Mumtaz's tomb after which Jai Singh agreed to give it to emperor Shah Jahan in exchange for a large palace in the centre of Agra.

The marble has been polished to emphasise the exquisite detailing of the carvings and the frames and archway spandrels are decorated with pietra dura inlays of stylised geometric pattern of vines, flowers and fruits.

The plinth is differentiated from the paved surface of the main platform by an interlocking pattern of octagonal white marble pieces set into four pointed stars made of red sandstone, surrounded by a border.

Staircases lead from the ground floor to the roof level, where there are corridors between the central hall and the two corner rooms in the south with a system of ventilation shafts.

[35] Each chamber wall is highly decorated with dado bas-relief, intricate lapidary inlay and refined calligraphy panels similar to the design elements seen throughout the exterior of the complex.

From the southern main entrance room, a stairway leads to the lower tomb chamber which is rectangular in shape with walls laid with marble and an undecorated coved ceiling.

The epitaph surrounded by red poppy flowers reads "This is the sacred grave of His Most Exalted Majesty, Dweller in Paradise (Firdaus Ashiyani), Second Lord of the Auspicious.

He travelled from this world to the banquet hall of eternity on the night of the twenty-sixth of the month of Rajab, in the year one thousand and seventy-six Hijri [31 January AD 1666]".

The main gateway, primarily built of marble, mirrors the tomb's architecture and incorporates intricate decorations like bas-relief and pietra dura inlays.

At the far end of the complex stand two similar buildings built of red sandstone, one of which is designated as a mosque and the other as a jawab, a structure to provide architectural symmetry.

Many precious and semi-precious stones, used for decoration, were imported from across the world, including jade and crystal from China, turquoise from Tibet, Lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, sapphire from Sri Lanka and carnelian from Arabia.

Specialist sculptors from Bukhara, calligraphers from Syria and Persia, designers from southern India, stone cutters from Baluchistan and Italian artisans were employed.

[50] When the structure was partially completed, the first ceremony was held at the mausoleum by Shah Jahan on 6 February 1643, of the 12th anniversary of the death of Mumtaz Mahal.

[4] In December 1652, Shah Jahan's son Aurangzeb wrote a letter to his father about the tomb, the mosque and the assembly hall of the complex developing extensive leaks during the previous rainy season.

Kanbo, a Mughal historian, said the gold shield which covered the 4.6-metre-high (15 ft) finial at the top of the main dome was also removed during the Jat despoliation.

[63][64] After directives by the Supreme Court of India, in 1997 the Indian government set up the "Taj Trapezium Zone (TTZ)", a 10,400-square-kilometre (4,000 sq mi) area around the monument where strict emissions standards are in place.

[74] Bilateral symmetry, dominated by a central axis, has historically been used by rulers as a symbol of a ruling force that brings balance and harmony, and Shah Jahan applied that concept in the making of the Taj Mahal.

[84][85][86][87] Ever since its construction, the building has been the source of an admiration transcending culture and geography, and so personal and emotional responses have consistently eclipsed scholastic appraisals of the monument.

Ruins of blackened marble across the river in the Mehtab Bagh seeming to support the argument were, however, proven false after excavations carried out in the 1990s found that they were discolored white stones that had turned black.

[90] No concrete evidence exists for claims that describe, often in horrific detail, the deaths, dismemberment and mutilations which Shah Jahan supposedly inflicted on various architects and craftsmen associated with the tomb.

[93] No evidence exists for claims that Lord William Bentinck, governor-general of India in the 1830s, supposedly planned to demolish the Taj Mahal and auction off the marble.

[95] Several myths, none of which are supported by the archaeological record, have appeared asserting that people other than Shah Jahan and the original architects were responsible for the construction of the Taj Mahal.

For instance, in 2000, India's Supreme Court dismissed P. N. Oak's petition to declare that a Hindu king built the Taj Mahal.

[93][96] In 2005, a similar petition brought by Amar Nath Mishra, a social worker and preacher claiming that the Taj Mahal was built by the Hindu king Paramardi in 1196, was dismissed by the Allahabad High Court.

[101] Another such unsupported theory, that the Taj Mahal was designed by an Italian, Geronimo Vereneo, held sway for a brief period after it was first promoted by Henry George Keene in 1879.

Another theory, that a Frenchman named Austin of Bordeaux designed the Taj, was promoted by William Henry Sleeman based on the work of Jean-Baptiste Tavernier.