Tangena

The belief in the genuineness and accuracy of the tangena ordeal was so strongly held among all that innocent people suspected of an offence did not hesitate to subject themselves to it; some even showed eagerness to be tested.

The name Tangena - designating both the plant and the ordeal in which it was used - is derived from a word in the official (highland) dialect of the Malagasy language, tangaina, meaning "swearing" or "oath taking".

The 19th century transcription of Merina oral history, Tantara ny Andriana eto Madagasikara, references the use of tangena by the Merina king Andrianjaka (1612–1630), describing a change in its practice: rather than administering tangena poison to an accused person's rooster to determine their innocence by the creature's survival, the poison would instead be ingested by the accused himself.

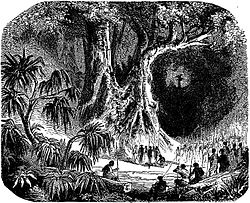

Although many versions of the ordeal were practiced, the basic procedure involved feeding the accused three pieces of chicken skin, followed by a mixture of the poison and leaves or juice from banana or the cardamom plant.

[4] According to 19th-century Malagasy historian Raombana, in the eyes of the greater populace, the tangena ordeal was believed to represent a sort of celestial justice in which the public placed their unquestioning faith, even to the point of accepting a verdict of guilt in a case of innocence as a just but unknowable divine mystery.

[6][9] One of the key conditions that Radama's widow, Rasoherina, was obliged to accept by her ministers before they would agree to her succession, was continued adherence to the abolishment of the tangena ordeal.

It was widely believed among the Malagasy that the various foods and drinks consumed during the ritual could alter the toxicity of the nuts, and so only a certain group of "witch doctors" were allowed to carry out the trial.