Tarski's axioms

Tarski's axioms are an axiom system for Euclidean geometry, specifically for that portion of Euclidean geometry that is formulable in first-order logic with identity (i.e. is formulable as an elementary theory).

Using his axiom system, Tarski was able to show that the first-order theory of Euclidean geometry is consistent, complete and decidable: every sentence in its language is either provable or disprovable from the axioms, and we have an algorithm which decides for any given sentence whether it is provable or not.

Early in his career Tarski taught geometry and researched set theory.

His coworker Steven Givant (1999) explained Tarski's take-off point: Givant then says that "with typical thoroughness" Tarski devised his system: Like other modern axiomatizations of Euclidean geometry, Tarski's employs a formal system consisting of symbol strings, called sentences, whose construction respects formal syntactical rules, and rules of proof that determine the allowed manipulations of the sentences.

Such economy of primitive and defined notions means that Tarski's system is not very convenient for doing Euclidean geometry.

This fact allowed Tarski to prove that Euclidean geometry is decidable: there exists an algorithm which can determine the truth or falsity of any sentence.

This does not contradict Gödel's first incompleteness theorem, because Tarski's theory lacks the expressive power needed to interpret Robinson arithmetic (Franzén 2005, pp. 25–26).

The work of Tarski and his students on Euclidean geometry culminated in the monograph Schwabhäuser, Szmielew, and Tarski (1983), which set out the 10 axioms and one axiom schema shown below, the associated metamathematics, and a fair bit of the subject.

Gupta (1965) made important contributions, and Tarski and Givant (1999) discuss the history.

These axioms are a more elegant version of a set Tarski devised in the 1920s as part of his investigation of the metamathematical properties of Euclidean plane geometry.

This is essentially the Dedekind cut construction, carried out in a way that avoids quantification over sets.

Without this axiom, the theory could be modeled by the one-dimensional real line, a single point, or even the empty set.

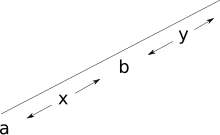

For any point y, it is possible to draw in any direction (determined by x) a line congruent to any segment ab.

The Identity of Congruence and of Betweenness govern the trivial case when those relations are applied to nondistinct points.

When the number of dimensions is greater than 1, Betweenness can be defined in terms of congruence (Tarski and Givant, 1999).

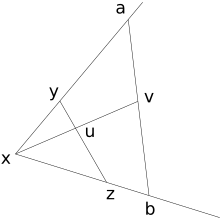

Betweenness can then be defined by using the intuition that the shortest distance between any two points is a straight line: The Axiom Schema of Continuity assures that the ordering of points on a line is complete (with respect to first-order definable properties).

Indeed, it is shown in (Schwabhäuser 1983) that by specifying two distinguished points on a line, called 0 and 1, we can define an addition, multiplication and ordering, turning the set of points on that line into a real-closed ordered field.

An example of a theorem of Euclidean geometry which cannot be so formulated is the Archimedean property: to any two positive-length line segments S1 and S2 there exists a natural number n such that nS1 is longer than S2.

[5]) Other notions that cannot be expressed in Tarski's system are the constructability with straightedge and compass and statements that talk about "all polygones" etc.

[6] Gupta (1965) proved the Tarski's axioms independent, excepting Pasch and Reflexivity of Congruence.

Full (as opposed to elementary) Euclidean geometry requires giving up a first order axiomatization: replace φ(x) and ψ(y) in the axiom schema of Continuity with x ∈ A and y ∈ B, where A and B are universally quantified variables ranging over sets of points.

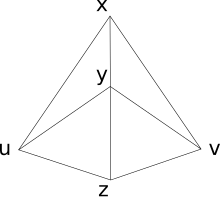

The only notion from intuitive geometry invoked in the remarks to Tarski's axioms is triangle.

(Versions B and C of the Axiom of Euclid refer to "circle" and "angle," respectively.)

In addition to betweenness and congruence, Hilbert's axioms require a primitive binary relation "on," linking a point and a line.

Such a schema is indispensable; Euclidean geometry in Tarski's (or equivalent) language cannot be finitely axiomatized as a first-order theory.

Hilbert's system is therefore considerably stronger: every model is isomorphic to the real plane