Tekhelet

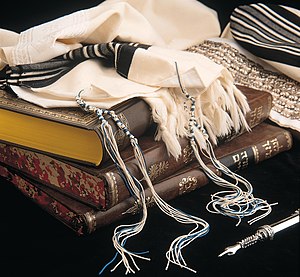

In the Hebrew Bible and Jewish tradition, tekhelet was used to colour the clothing of the High Priest of Israel, the tapestries in the Tabernacle, and the tzitzit (fringes) attached to the corners of four-cornered garments, including the tallit.

According to later rabbinic literature, it was exclusively derived from a marine creature known as the ḥillāzon (חלזון, from Ancient Greek: ἑλικών, romanized: helikṓn).

In recent times, many Jews believe that experts have identified the Ḥillazon and rediscovered the process for manufacturing tekhelet, leading to the revival of its use in tzitzit.

[8] Of the 49[9] or 48[4][10] uses of the word tekhelet in the Masoretic Text, one refers to fringes on cornered garments of the whole people of Israel (Numbers 15:37–41).

In the Amarna letters (14th century BCE) tekhelet garments are listed as a precious good used for a royal dowry.

[13] At some point following the Roman destruction of the Second Temple during the Siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE, the identity of the source of the dye was lost, and since then Jews have only worn tzitzit without tekhelet.

[15] Nero made laws that stated no one was allowed to wear purple because it was the color of royalty, and specifically he forbade goods dyed with purpura, the name used for H. trunculus under penalty of death.

[19] In the sixth century, Justinian put the tekhelet and Tyrian purple industries under a royal monopoly, causing independent dyers to cease their work and find other employment.

[20] Some have argued that the use of tekhelet persisted (at least in certain locations) for several centuries beyond the Muslim conquest, based on texts from the geonim and early rishonim which discuss the commandment in practical terms.

[22] Despite the general agreement of most of the modern English translations of the phrase, the term tekhelet itself presents several basic problems.

The task is made harder by the tendency of ancient writers to identify colours not so much by their hue as by other factors such as luminosity, saturation and texture.

[24] The colour of tekhelet was likely to have varied in practice, as ancient dyers were generally unable to reproduce exact shades from one batch of dye to another.

[26] In the early classical sources (Septuagint, Aquila, Symmachus, Vulgate, Philo, and Josephus), tekhelet was translated into Koine Greek as hyakinthos (ὑακίνθος, "hyacinth") or the Latin equivalent.

In the 1980s, Otto Elsner, a chemist from the Shenkar College of Fibers in Israel, discovered that if a solution of the dye was exposed to ultraviolet rays such as from sunlight, blue instead of purple was consistently produced.

[55][56] In 1988, Rabbi Eliyahu Tavger dyed tekhelet from H. trunculus for the commandment of Tzitzit for the first time in recent history.

The television show The Naked Archaeologist interviews an Israeli scientist who also makes the claim that this mollusk is the correct animal.

[59] Chemical testing of ancient blue-dyed cloth from the appropriate time period in Israel reveals that a sea snail-based dye was used.

[61] Hexaplex opponents suggest that in ancient times the word might have referred to a broader category of animals, perhaps including other candidate species such as the cuttlefish.

[58][67] The word porforin, or porpora, or porphoros is used in the midrash as well as many other Jewish texts to refer to the Ḥillazon, and this is the Greek[68] translation of Murex trunculus.

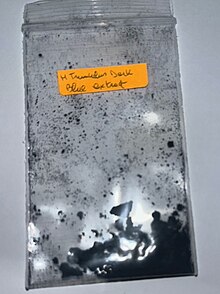

[58] According to Dr. Israel Irving Ziderman's writings in the 1980s,[70] the test consists of a chemical reduction reaction occurring when hydrogen is produced by decaying organic matter.

Hexaplex supporters argue that many forms of aquatic life (e.g., shellfish — of which sea snails would be an example) are also called "דגים" in Hebrew.

[70] Other sources claim that the 70-year cycle was a miraculous occurrence which no longer occurs or else that the decrease in Hexaplex population numbers may have caused this behaviour to cease.

All sea-based creatures, aside from having the Halachic status of a "fish", on a more practical level are impossible for the average person to gather without some form of trapping, and in fact, even today are caught with nets [75] or wicker baskets.

[76] Maimonides described the ḥillāzon, stating that "its blood is as black as ink",[77] which does not seem to match the characteristics of Hexaplex.

"[79] Tractate Menachot[80] and the Rambam explain the process for making the dye for tekhelet, and neither of them mention explicitly that it needs to be placed in the sunlight.

[81] In 1887, Grand Rabbi Gershon Henoch Leiner, the Radziner Rebbe, researched the subject and concluded that Sepia officinalis (common cuttlefish) met many of the criteria.

The chemists concluded that it was a well-known synthetic dye "Prussian blue" made by reacting iron(II) sulfate with an organic material.

[82] Within his doctoral research on the subject of tekhelet, Herzog placed great hopes on demonstrating that H. trunculus was the genuine ḥillāzon.

Beit Halevi argued (when debating the Radziner rebbe) that a continuous tradition regarding the source of the dye, which no longer exists, was necessary in order for it to be used.

Like their non-Jewish neighbors, Jews of the Middle East painted their doorposts, and other parts of their homes with blue dyes; have ornamented their children with tekhelet ribbons and markings; and have used this color in protective amulets.