Templo Mayor

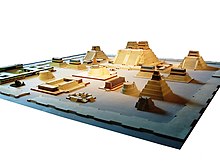

[2] The temple devoted to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc, measuring approximately 100 by 80 m (328 by 262 ft) at its base, dominated the Sacred Precinct.

[4] The Zócalo, or main plaza of Mexico City today, was developed to the southwest of Templo Mayor, which is located in the block between Seminario and Justo Sierra streets.

[4] In the first decades of the 20th century, Manuel Gamio found part of the southwest corner of the temple, and his findings were put on public display.

[9] To complete the excavation, 13 buildings in this area were demolished including 9 built in the 1930s and 4 dating from the 19th century that had preserved colonial elements.

During excavations, more than 7,000 objects were found, mostly offerings including effigies; clay pots in the image of Tlaloc; skeletons of turtles, frogs, crocodiles, and fish; snail shells; coral; gold; alabaster; Mixtec figurines; ceramic urns from Veracruz; masks from what is now Guerrero state; copper rattles; and decorated skulls and knives of obsidian and flint.

[5] This museum is the result of the work done since the early 1980s to rescue, preserve, and investigate Templo Mayor, its Sacred Precinct, and all objects associated with it while making these findings available to the public.

[9] The excavated site consists of two parts: 1) the temple itself, exposed and labeled to show its various stages of development, along with some other associated buildings, and 2) the museum, built to house the smaller and more fragile objects.

[9] The process of expanding an Aztec temple was typically completed by new structures being built over earlier ones, using the bulk of the former as a base for the latter.

The two temples were approximately 60 meters (200 feet) in height, including the pyramid,[12] and each had large braziers where the sacred fires continuously burned.

The entrance to each temple had statues of robust and seated men which supported the standard-bearers and banners of handmade bark paper.

This figure was constructed annually, and it was richly dressed and fitted with a mask of gold for his festival held during the Aztec month of Panquetzaliztli.

[7] In his description of the city, Cortés records that he and the other Spaniards were impressed by the number and magnificence of the temples constructed in Tenochtitlan, but that was tempered by this disdain for their beliefs and human sacrifice.

When word of the massacre spread throughout the city, the people turned on the Spaniards, killing seven, wounding many, and driving the rest back to their quarters.

The sacrificed Spaniards were flayed, and their faces – with beards attached – were tanned and sent to allied towns, both to solicit assistance and to warn against betraying the Triple Alliance.

[4] Fray Toribio de Motolinía, a Spanish friar who arrived to Mexico soon after the invasion, writes in his work Memoriales that the Aztec feast of Tlacaxipehualiztli "took place when the sun stood in the middle of [the Temple of] Huitzilopochtli, which was at the equinox".

One of the sunset dates corresponding to the east–west axis of the late stages, including the last, is 4 April, which in the Julian calendar of the 16th century was equivalent to 25 March.

Consequently, Motolinía did not refer to the astronomical equinox (the date of which would have hardly been known to a non-astronomer at that time), but rather only pointed out the correlation between the day of the Mexica festival, which in the last years before the invasion coincided with the solar phenomenon in the Templo Mayor, and the date in the Christian calendar that corresponded to the traditional day of spring equinox.

[17] According to tradition, the Templo Mayor is located on the exact spot where the god Huitzilopochtli gave the Mexica people his sign that they had reached the promised land: an eagle on a nopal cactus with a snake in its mouth.

[7] The Templo Mayor was partially a symbolic representation of the Hill of Coatepec, where according to Mexica myth, Huitzilopochtli was born.

[10][18] The sacred ballcourt and skull rack were located at the foot of the stairs of the twin temples, to mimic, like the stone disk, where Huitzilopochtli was said to have placed the goddess' severed head.

[10] Archaeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, in his essay "Symbolism of the Templo Mayor", posits that the orientation of the temple is indicative of the total vision that the Mexica had of the universe (cosmovision).

"[19] Matos Moctezuma supports his supposition by claiming that the temple acts as an embodiment of a living myth where "all sacred power is concentrated and where all the levels intersect."

The lower panel shows processions of armed warriors converging on a zacatapayolli, a grass ball into which the Mexica stuck bloody lancets during the ritual of autosacrifice.

Sculptures, flint knives, vessels, beads and other sumptuary ornaments—as well as minerals, plants and animals of all types, and the remains of human sacrifice—were among the items deposited in offerings.

In 1991, the Urban Archeology Program was incorporated as part of the Templo Mayor Project whose mission is to excavate the oldest area of the city, around the main plaza.

[4] The museum building was built by architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez, who envisioned a discreet structure that would blend in with the colonial surroundings.

This room contains urns where dignitaries where interred, funerary offerings, as well as objects associated with self and human sacrifice—such as musical instruments, knives and skulls.

Room 3 demonstrates the economics of the Aztec empire in the form of tribute and trade, with examples of finished products and raw materials from many parts of Mesoamerica.

Also located here are the two large ceramic statues of the god Mictlantecuhtli which were found in the House of the Eagle Warriors who were dedicated to Huitzilopochtli.

The most prized work is a large pot with the god's face in high relief that still preserves much of the original blue paint.