Term (logic)

An expression formed by applying a predicate symbol to an appropriate number of terms is called an atomic formula, which evaluates to true or false in bivalent logics, given an interpretation.

is a term built from the constant 1, the variable x, and the binary function symbols

Besides in logic, terms play important roles in universal algebra, and rewriting systems.

Ternary operations and higher-arity functions are possible but uncommon in practice.

A term denotes a mathematical object from the domain of discourse.

The latter term is usually written as n+1, using infix notation and the more common operator symbol + for convenience.

Originally, logicians defined a term to be a character string adhering to certain building rules.

Two terms are said to be structurally, literally, or syntactically equal if they correspond to the same tree.

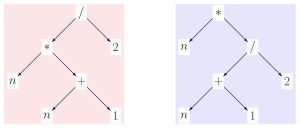

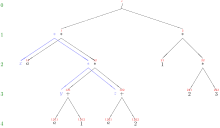

For example, the left and the right tree in the above picture are structurally unequal terms, although they might be considered "semantically equal" as they always evaluate to the same value in rational arithmetic.

If the function / is e.g. interpreted not as rational but as truncating integer division, then at n=2 the left and right term evaluates to 3 and 2, respectively.

Structural equal terms need to agree in their variable names.

In many contexts, the particular variable names in a term don't matter, e.g. the commutativity axiom for addition can be stated as x+y=y+x or as a+b=b+a; in such cases the whole formula may be renamed, while an arbitrary subterm usually may not, e.g. x+y=b+a is not a valid version of the commutativity axiom.

Abbreviating the number of constants as f0, and the number of i-ary function symbols as fi, the number θh of distinct ground terms of a height up to h can be computed by the following recursion formula: Given a set Rn of n-ary relation symbols for each natural number n ≥ 1, an (unsorted first-order) atomic formula is obtained by applying an n-ary relation symbol to n terms.

As for function symbols, a relation symbol set Rn is usually non-empty only for small n. In mathematical logic, more complex formulas are built from atomic formulas using logical connectives and quantifiers.

⇒ (x+1)⋅(x+1) ≥ 0 is a mathematical formula evaluating to true in the algebra of complex numbers.

An atomic formula is called ground if it is built entirely from ground terms; all ground atomic formulas composable from a given set of function and predicate symbols make up the Herbrand base for these symbol sets.

When the domain of discourse contains elements of basically different kinds, it is useful to split the set of all terms accordingly.

For example, a vector space comes with an associated field of scalar numbers.

and 0 ∈ CN, and the vector addition, the scalar multiplication, and the inner product is declared as

Mathematical notations as shown in the table do not fit into the scheme of a first-order term as defined above, as they all introduce an own local, or bound, variable that may not appear outside the notation's scope, e.g.

All these operators can be viewed as taking a function rather than a value term as one of their arguments.

For example, the lim operator is applied to a sequence, i.e. to a mapping from positive integer to e.g. real numbers.

Lambda terms can be used to denote anonymous functions to be supplied as arguments to lim, Σ, ∫, etc.

For example, the function square from the C program below can be written anonymously as a lambda term λi.

The general sum operator Σ can then be considered as a ternary function symbol taking a lower bound value, an upper bound value and a function to be summed-up.

Due to its latter argument, the Σ operator is called a second-order function symbol.

The lim operator takes such a sequence and returns its limit (if defined).

The rightmost column of the table indicates how each mathematical notation example can be represented by a lambda term, also converting common infix operators into prefix form.

Given a set V of variable symbols, the set of lambda terms is defined recursively as follows: The above motivating examples also used some constants like div, power, etc.

Intuitively, the abstraction λx.t denotes a unary function that returns t when given x, while the application ( t1 t2 ) denotes the result of calling the function t1 with the input t2.