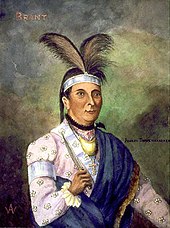

Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (March 1743 – November 24, 1807) was a Mohawk military and political leader, based in present-day New York and, later, Brantford, in what is today Ontario, who was closely associated with Great Britain during and after the American Revolution.

[10] Brant's mother Margaret was a successful businesswoman who collected and sold ginseng, which was greatly valued in Europe for its medical qualities, selling the plant to New York merchants who shipped it to London.

[12] In 1752, Margaret began living with Brant Canagaraduncka (alternative spelling: Kanagaraduncka), a Mohawk royaner, and in March 1753 bore him a son named Jacob, which greatly offended the local Church of England minister, the Reverend John Ogilvie, when he discovered that they were not married.

[43] While traveling to German Flatts, Brant felt first-hand the "fear and hostility" held by the whites of Tryon County who hated him both for his tactics against Klock and as a friend of the powerful Johnson family.

[45] The governor of Quebec, General Guy Carleton, personally disliked Johnson, felt his plans for employing the Iroquois against the rebels to be inhumane, and treated Brant with barely veiled contempt.

[48] Paxton commented it was a mark of Brant's charisma and renown that white Loyalists preferred to fight under the command of a Mohawk chief who was unable to pay or arm them while at the same time that only a few Iroquois joined him reflected the generally neutralist leanings of most of the Six Nations.

Brant was not present, but was deeply saddened when he learned that Six Nations had broken into two with the Oneida and Tuscarora supporting the Americans while the Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca chose the British.

[54] The British Army officers found Molly Brant to be bad-tempered and demanding, as she expected to be well rewarded for her loyalty to the Crown, but as she possessed much influence, it was felt to be worth keeping her happy.

Helmer took off running to the north-east, through the hills, toward Schuyler Lake and then north to Andrustown (near present-day Jordanville, New York) where he warned his sister's family of the impending raid and obtained fresh footwear.

[citation needed] In October 1778, Lieutenant Colonel William Butler led 300 Continental soldiers and New York militia attacked Brant's home base at Onaquaga while he and his volunteers were away on a raid.

One British officer, Colonel Mason Bolton, the commander of Fort Niagara, described in a report to Sir Frederick Haldimand, described Brant as treating all prisoners he had taken "with great humanity".

[61] Morton wrote: "An American historian, Barbara Graymount, has carefully demolished most of the legend of savage atrocities attributed to the Rangers and the Iroquois and confirmed Joseph Brant's own reputation as a generally humane and forbearing commander".

[69] Over the course of a year, Brant and his Loyalist forces had reduced much of New York and Pennsylvania to ruins, causing thousands of farmers to flee what had been one of the most productive agricultural regions on the eastern seaboard.

To disrupt the Americans' plans, John Butler sent Brant and his Volunteers on a quest for provisions and to gather intelligence in the upper Delaware River valley near Minisink, New York.

To escape the Sullivan expedition, about 5,000 Senecas, Cayugas, Mohawks and Onondagas fled to Fort Niagara, where they lived in squalor, lacking shelter, food and clothing, which caused many to die over the course of the winter.

Joining with Butler's Rangers and the King's Royal Regiment of New York, Brant's forces were part of a third major raid on the Mohawk Valley, where they destroyed settlers' homes and crops.

Through a long and involved process between March and the end of November 1782, the preliminary peace treaty between Great Britain and America would be made; it would become public knowledge following its approval by the Congress of the Confederation on April 15, 1783.

The difference between the two lines was the whole area south of the Great Lakes, north of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi, in which the Six Nations and western Indian tribes were previously accepted as sovereign.

Brant expressed extreme indignation on learning that the commissioners had detained as hostages several prominent Six Nations leaders and delayed his intended trip to England attempting to secure their release.

With Brant's urging and three days later, Haldimand proclaimed a grant of land for a Mohawk reserve on the Grand River in the western part of the Province of Quebec (present-day Ontario) on October 25, 1784.

Brant's home had a white fence, a Union Flag flying in front, and was described as being equipped with "chinaware, fine furniture, English sheets, and a well-stocked liquor cabinet".

[87] During his time in London, Brant attended masquerade balls, visited the freak shows, dined with the debauched Prince of Wales and finished the Anglican Mohawk Prayer Book that he had begun before the war.

From 1790 onward, Brant had been planning on selling much of the land along the Grand river granted by the Haldimand proclamation and using the money from the sales to finance the modernization of the Haudenosaunee community to allow them equal standing with the European population.

[90] The issue resolved itself later that year when during the distribution of presents from the Crown to the Iroquois chiefs at Head of the Lake (modern Burlington, Ontario), Issac had too much to drink in the local tavern and began to insult his father.

[90] Joseph Brant happened to be in a neighbouring room, and upon hearing what Issac was saying, marched in and ordered his son to be silent, reminding him that insulting one's parents was a grave breach of courtesy for the Mohawk.

[102] The governor of Upper Canada, Peter Russell, felt threatened by the pan-Indian alliance, telling the Indian Department officials to "foment any existing Jealously between the Chippewas [Mississauga] & the Six Nations and to prevent ... any Junction or good understanding between these two Tribes".

Peter Russell wrote: "the present alarming aspect of affairs – when we are threatened with an invasion by the French and Spaniards from the Mississippi, and the information we have received of emissaries being dispersed among the Indian tribes to incite them to take up the hatchet against the King's subjects.

"[citation needed] In September 1797, London had decided that the Indian Department was too sympathetic towards the Iroquois, and transferred authority from dealing with them to the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, Russell, a move that Brant was openly displeased with.

[114] The American historian Douglas Boyce wrote Brant's answers which portrayed the genesis of the Iroquois Confederacy as due to rational statesmanship on the part of the chiefs instead of the workings of magic suggested that either Brant was ignoring the supernatural aspects of the story in order to appeal to a white audience or that alternatively that white American and Canadian ethnologists, anthropologists, and historians have played up the emphasis on the supernatural in the story of the birth of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy in order to depict the Haudenosaunee as a primitive and irrational people.

Two, in particular, signify his place in American, Canadian, and British history: In 1984–85, crews from The University at Albany under the direction of David Guldenzopf, supervised by Dean Snow investigated the late Mohawk site at "Indian Castle" (Dekanohage) in Herkimer County, New York.