Bastille

[1] Prior to the Bastille, the main royal castle in Paris was the Louvre, in the west of the capital, but the city had expanded by the middle of the 14th century and the eastern side was now exposed to an English attack.

[1] The situation worsened after the imprisonment of John II in England following the French defeat at the Battle of Poitiers, and in his absence the Provost of Paris, Étienne Marcel, took steps to improve the capital's defences.

[12] The fortress had four sets of drawbridges, which allowed the Rue Saint-Antoine to pass eastwards through the Bastille's gates while giving easy access to the city walls on the north and south sides.

[14] Charles V chose to live close to the Bastille for his own safety and created a royal complex to the south of the fortress called the Hôtel Saint-Pol, stretching from the Porte Saint-Paul up to the Rue Saint-Antoine.

[16] The Bastille's design was highly innovative: it rejected both the 13th-century tradition of more weakly fortified quadrangular castles, and the contemporary fashion set at Vincennes, where tall towers were positioned around a lower wall, overlooked by an even taller keep in the centre.

[25] The castle remained a key Parisian fortress, but was successfully seized by the Burgundians in 1464, when they convinced royal troops to surrender: once taken, this allowed their faction to make a surprise attack into Paris, almost resulting in the capture of the king.

[32] The Arsenal, a large military-industrial complex tasked with the production of cannons and other weapons for the royal armies, was established to the south of the Bastille by Francis I, and substantially expanded under Charles IX.

[59] Condé's forces became trapped against the city walls and the Porte Saint-Antoine, which the Parlement refused to open; he was coming under increasingly heavy fire from the Royalist artillery and the situation looked bleak.

[69] By Louis's reign, Bastille prisoners were detained using a lettre de cachet, a letter under royal seal, issued by the king and countersigned by a minister, ordering a named person to be held.

[84] By the late 18th century, the Bastille had come to separate the more aristocratic quarter of The Marais in the old city from the working class district of the faubourg Saint-Antoine that lay beyond the Louis XIV boulevard.

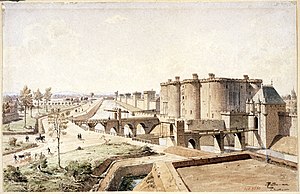

[89] The eight stone towers had gradually acquired individual names: running from the north-east side of the external gate, these were La Chapelle, Trésor, Comté, Bazinière, Bertaudière, Liberté, Puits and Coin.

This was open to the public and lined with small shops rented out by the governor for almost 10,000 livres a year, complete with a lodge for the Bastille gatekeeper; it was illuminated at night to light the adjacent street.

These cases typically involving members of the aristocracy who had, as historian Richard Andrews notes, "rejected parental authority, disgraced the family reputation, manifested mental derangement, squandered capital or violated professional codes.

[115] In the aftermath of the notorious "Affair of the Diamond Necklace" of 1786, involving Queen Marie Antoinette and accusations of fraud, all the eleven suspects were held in the Bastille, significantly increasing the notoriety surrounding the institution.

Although appointed by the king, the governor reported to the lieutenant general of police: the first of these, Gabriel Nicolas de la Reynie, made only occasional visits to the Bastille, but his successor, Marquis d'Argenson, and subsequent officers used the facility extensively and took a close interest in inspections of the prison.

[74] The writer Laurent Angliviel de la Beaumelle, the philosopher André Morellet and the historian Jean-François Marmontel, for example, were formally detained not for their more obviously political writings, but for libellous remarks or for personal insults against leading members of Parisian society.

[154] Latude became famous for managing to escape from the Bastille by means of climbing up the chimney of his cell and then descending the walls with a home-made rope ladder, before being recaptured in Amsterdam by French agents.

[158][Q] Modern historians of the period, such as Hans-Jürgen Lüsebrink, Simon Schama and Monique Cottret (fr), concur that the actual treatment of prisoners in Bastille was much better than the public impression left through those writings.

[170] At de Launay's request, an additional force of 32 soldiers from the Swiss Salis-Samade regiment had been assigned to the Bastille on 7 July, adding to the existing 82 invalides pensioners who formed the regular garrison.

[170] De Launay had taken various precautions, raising the drawbridge in the Comté tower and destroying the stone abutment that linked the Bastille to its bastion to prevent anyone from gaining access from that side of the fortress.

[170] The Bastille, already hugely unpopular with the revolutionary crowds, was now the only remaining royalist stronghold in central Paris, in addition to which he was protecting a recently arrived stock of 250 barrels of valuable gunpowder.

[174] Just after midday, another negotiator was let in to discuss the situation, but no compromise could be reached: the revolutionary representatives now wanted both the guns and the gunpowder in the Bastille to be handed over, but de Launay refused to do so unless he received authorisation from his leadership in Versailles.

[181] De Launay had limited options: if he allowed the Revolutionaries to destroy his main gate, he would have to turn the cannon directly inside the Bastille's courtyard on the crowds, causing great loss of life and preventing any peaceful resolution of the episode.

[186] The faubourg Saint-Antoine's revolutionary reputation was firmly established by their storming of the Bastille and a formal list began to be drawn up of the vainqueurs, or "the victorious", who had taken part so as to honour both the fallen and the survivors.

[189] The fortress itself was described by the revolutionary press as a "place of slavery and horror", containing "machines of death", "grim underground dungeons" and "disgusting caves" where prisoners were left to rot for up to 50 years.

[192] Stories and pictures about the rescue of the fictional Count de Lorges – supposedly a mistreated prisoner of the Bastille incarcerated by Louis XV – and the similarly imaginary discovery of the skeleton of the "Man in the Iron Mask" in the dungeons, were widely circulated as fact across Paris.

[191] Of the remaining six liberated prisoners, four were convicted forgers who quickly vanished into the Paris streets; one was the Count Hubert de Solages, who had been imprisoned on the request of his family for sexual misdemeanours; the sixth was Auguste-Claude Tavernier, who also proved to be mentally ill and, along with Whyte, was in due course reincarcerated in the Charenton asylum.

[199] The revolutionary leader Mirabeau eventually settled the matter by symbolically starting the destruction of the battlements himself, after which a panel of five experts was appointed by the Permanent Committee of the Hôtel de Ville to manage the demolition of the castle.

In 1889 the continued popularity of the Bastille with the public was illustrated by the decision to build a replica in stone and wood for the Exposition Universelle world fair in Paris, manned by actors in period costumes.

[246] The Bibliothèque nationale de France held a major exhibition on the legacy of the Bastille between 2010 and 2011, resulting in a substantial edited volume summarising the current academic perspectives on the fortress.