Black Country

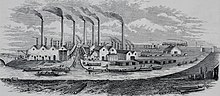

Either the 30-foot-thick coal seam close to the surface[5] or the mix of coalworks, cokeworks, ironworks, glassworks, brickworks and steelworks (which produced high levels of soot and air pollution at the time) led to the area's name, which was first recorded in the 1840s.

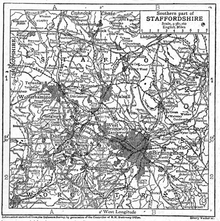

Some traditionalists define it as "the area where the coal seam comes to the surface – so West Bromwich, Coseley, Oldbury, Blackheath, Cradley Heath, Old Hill, Bilston, Dudley, Tipton, Wednesbury, and parts of Halesowen, Walsall and Smethwick or what used to be known as Warley.

[8][9] Bilston-born Samuel Griffiths, in his 1876 Griffiths Guide to the Iron Trade of Great Britain, stated "The Black Country commences at Wolverhampton, extends a distance of sixteen miles to Stourbridge, eight miles to West Bromwich, penetrating the northern districts through Willenhall to Bentley, The Birchills, Walsall and Darlaston, Wednesbury, Smethwick and Dudley Port, West Bromwich and Hill Top, Brockmoor, Wordsley and Stourbridge.

As the atmosphere becomes purer, we get to the higher ground of Brierley Hill, nevertheless here also, as far as the eye can reach, on all sides, tall chimneys vomit forth great clouds of smoke".

Today the term commonly refers to the majority of the four metropolitan boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton[3] although it is said that "no two Black Country men or women will agree on where it starts or ends".

[citation needed] The first recorded use of the term "the Black Country" may be from a toast given by a Mr Simpson, town clerk to Lichfield, addressing a Reformer's meeting on 24 November 1841, published in the Staffordshire Advertiser.

[19] In published literature, the first reference dates from 1846 and occurs in the novel Colton Green: A Tale of the Black Country[20] by the Reverend William Gresley, who was then a prebendary of Lichfield Cathedral.

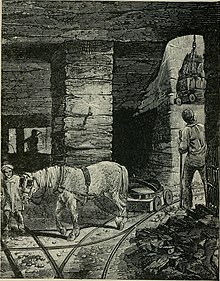

The pleasant green of pastures is almost unknown, the streams, in which no fishes swim, are black and unwholesome; the natural dead flat is often broken by high hills of cinders and spoil from the mines; the few trees are stunted and blasted; no birds are to be seen, except a few smoky sparrows; and for miles on miles a black waste spreads around, where furnaces continually smoke, steam engines thud and hiss, and long chains clank, while blind gin horses walk their doleful round.

The majority of the natives of this Tartarian region are in full keeping with the scenery – savages, without the grace of savages, coarsely clad in filthy garments, with no change on weekends or Sundays, they converse in a language belarded with fearful and disgusting oaths, which can scarcely be recognised as the same as that of civilized England.This work was also the first to explicitly distinguish the area from nearby Birmingham, noting that "On certain rare holidays these people wash their faces, clothe themselves in decent garments, and, since the opening of the South Staffordshire Railway, take advantage of cheap excursion trains, go down to Birmingham to amuse themselves and make purchases.

"[26] The geologist Joseph Jukes made it clear in 1858 that he felt the meaning of the term was self-explanatory to contemporary visitors, remarking that "It is commonly known in the neighbourhood as the 'Black Country', an epithet the appropriateness of which must be acknowledged by anyone who even passes through it on a railway".

[23] An alternative theory for the meaning of the name is proposed as having been caused by the darkening of the local soil due to the outcropping coal and the seam near the surface.

[28] Burritt had been appointed United States consul in Birmingham by Abraham Lincoln in 1864, a role that required him to report regularly on "facts bearing upon the productive capacities, industrial character and natural resources of communities embraced in their Consulate Districts" and as a result travelled widely from his home in Harborne, largely on foot, to explore the local area.

[29] Burritt's association with Birmingham dated back 20 years and he was highly sympathetic to the industrial and political culture of the town as well as being a friend to many of its leading citizens, so his portrait of the surrounding area was largely positive.

[30] Burritt used the term to refer to a wider area than its common modern usage, however, devoting the first third of the book to Birmingham, which he described as "the capital, manufacturing centre, and growth of the Black Country", and writing "plant, in imagination, one foot of your compass at the Town Hall in Birmingham, and with the other sweep a circle of twenty miles [30 km] radius, and you will have, 'the Black Country" (this area includes Coventry, Kidderminster and Lichfield).

[35] A number of Black Country villages developed into market towns and boroughs in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, notably Dudley, Walsall and Wolverhampton.

In 1583, the accounts of the building of Henry VIII's Nonsuch Palace record that nails were supplied by Reynolde Warde of Dudley at a cost of 11s 4d per thousand.

In the Black Country, the establishment of this device was associated with Richard Foley, son of a Dudley nailer, who built a slitting mill near Kinver in 1628.

Numerous small forges which then existed on every brook in the north of Worcestershire turned out successive supplies of sword blades and pike heads.

[48] In 1864 the first Black Country plant capable of producing mild steel by the Bessemer process was constructed at the Old Park Works in Wednesbury.

By Victorian times, the Black Country was one of the most heavily industrialised areas in Britain, and it became known for its pollution, particularly from iron and coal industries and their many associated smaller businesses.

This action commenced on 9 May in Wednesbury, at the Old Patent tube works of John Russell & Co. Ltd., and within weeks upwards of 40,000 workers across the Black Country had joined the dispute.

This was of national significance at a time when Britain and Germany were engaged in the Anglo-German naval arms race that preceded the outbreak of the First World War.

[50] One of the important consequences of the strike was the growth of organised labour across the Black Country, which was notable because until this point the area's workforce had effectively eschewed trade unionism.

Manufacturers like Rubery Owen, Chance Bros, Wilkins and Mitchell, GKN, John Thompson (company) and many more prospered from the post-war boom in Britain, with the West Midlands motor industry being a key driver of the economy.

Today this museum demonstrates Black Country crafts and industry from days gone by and includes many original buildings which have been transported and reconstructed at the site.

Chainmaking is still a viable industry in the Cradley Heath area where the majority of the chain for the Ministry of Defence and the Admiralty fleet is made in modern factories.

Unemployment rose drastically across the country during this period as a result of Conservative Prime Minister Thatcher's economic policies; later, in an implicit acknowledgement of the social problems this had caused, these areas were designated as Enterprise Zones, and some redevelopment occurred.

Charles Dickens's novel The Old Curiosity Shop, written in 1841, described how the area's local factory chimneys "Poured out their plague of smoke, obscured the light, and made foul the melancholy air".

The Black Country is served by the regional television services - BBC West Midlands, ITV Central and Made in Birmingham.

[90] Incidentally, the Express and Star, traditionally a Black Country paper, has expanded to the point where they sell copies from vendors in Birmingham city centre.