Mad (magazine)

It was widely imitated and influential, affecting satirical media, as well as the cultural landscape of the late 20th century, with editor Al Feldstein increasing readership to more than two million during its 1973–1974 circulation peak.

"[4] After Kurtzman's departure in 1956, new editor Al Feldstein swiftly brought aboard contributors such as Don Martin, Frank Jacobs, and Mort Drucker, and later Antonio Prohías, Dave Berg, and Sergio Aragonés.

More than a hundred new names made their Mad debuts including Brian Posehn, Maria Bamford, Ian Boothby, Luke McGarry, Akilah Hughes, and future Pulitzer Prize finalist Pia Guerra.

[21][22] Scores of artists and writers from the New York run also returned to the pages of the California-based issues including contributors Sergio Aragonés, Al Jaffee, Desmond Devlin, Tom Richmond, Peter Kuper, Teresa Burns Parkhurst, Rick Tulka, Tom Bunk, Jeff Kruse, Ed Steckley, Arie Kaplan, writer and former Senior Editor Charlie Kadau, and artist and former Art Director Sam Viviano.

Its approach was described by Dave Kehr in The New York Times: "Bob Elliott and Ray Goulding on the radio, Ernie Kovacs on television, Stan Freberg on records, Harvey Kurtzman in the early issues of Mad: all of those pioneering humorists and many others realized that the real world mattered less to people than the sea of sounds and images that the ever more powerful mass media were pumping into American lives.

It was magical, objective proof to kids that they weren't alone, that in New York City on Lafayette Street, if nowhere else, there were people who knew that there was something wrong, phony and funny about a world of bomb shelters, brinkmanship and toothpaste smiles.

"[34]Mad is often credited with filling a vital gap in political satire from the 1950s to 1970s, when Cold War paranoia and a general culture of censorship prevailed in the United States, especially in literature for teens.

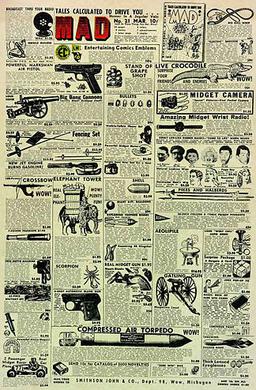

"[41] Mad also ran a good deal of less topical or contentious material on such varied subjects as fairy tales, nursery rhymes, greeting cards, sports, small talk, poetry, marriage, comic strips, awards shows, cars and many other areas of general interest.

[42][43] In 2007, the Los Angeles Times' Robert Boyd wrote, "All I really need to know I learned from Mad magazine", going on to assert: Plenty of it went right over my head, of course, but that's part of what made it attractive and valuable.

The magazine instilled in me a habit of mind, a way of thinking about a world rife with false fronts, small print, deceptive ads, booby traps, treacherous language, double standards, half truths, subliminal pitches and product placements; it warned me that I was often merely the target of people who claimed to be my friend; it prompted me to mistrust authority, to read between the lines, to take nothing at face value, to see patterns in the often shoddy construction of movies and TV shows; and it got me to think critically in a way that few actual humans charged with my care ever bothered to.

"[47] Graydon Carter chose it as the sixth-best magazine of any sort ever, describing Mad's mission as being "ever ready to pounce on the illogical, hypocritical, self-serious and ludicrous" before concluding, "Nowadays, it's part of the oxygen we breathe.

The magazine has also included recurring gags and references, both visual (e.g. the Mad Zeppelin, or Arthur the potted plant) and linguistic (unusual words such as axolotl, furshlugginer, potrzebie and veeblefetzer).

Following the magazine's parody of the film The Empire Strikes Back, a letter from George Lucas's lawyers arrived in Mad's offices demanding that the issue be recalled for infringement on copyrighted figures.

"[65] Mad was one of several parties that filed amicus curiae briefs with the Supreme Court in support of 2 Live Crew and its disputed song parody, during the 1993 Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.

But Bill Gaines was intractable, telling the television news magazine 60 Minutes, "We long ago decided we couldn't take money from Pepsi-Cola and make fun of Coca-Cola."

[68] Among the notable artists were the aforementioned Davis, Elder and Wood, as well as Sergio Aragonés, Mort Drucker, Don Martin, Dave Berg, George Woodbridge, Harry North and Paul Coker.

Over the years, the Mad crew traveled to such locales as France, Kenya, Russia, Hong Kong, England, Amsterdam, Tahiti, Morocco, Italy, Greece, and Germany.

[70] However, just how much of that success was due to the original Kurtzman template that he left for his successor, and how much should be credited to the Al Feldstein system and the depth of the post-Kurtzman talent pool, can be argued without resolution.

Newer contributors who appeared in the years that followed include Joe Raiola, Charlie Kadau, Tony Barbieri, Scott Bricher, Tom Bunk, John Caldwell, Desmond Devlin, Drew Friedman, Barry Liebmann, Kevin Pope, Scott Maiko, Hermann Mejia, Tom Richmond, Andrew J. Schwartzberg, Mike Snider, Greg Theakston, Nadina Simon, Rick Tulka, and Bill Wray.

However, Salon's David Futrelle opined that such content was very much a part of Mad's past: The October 1971 issue, for example, with its war crimes fold-in and back cover "mini-poster" of "The Four Horsemen of the Metropolis" (Drugs, Graft, Pollution and Slums).

[78]Mad editor John Ficarra acknowledged that changes in culture made the task of creating fresh satire more difficult, telling an interviewer, "The editorial mission statement has always been the same: 'Everyone is lying to you, including magazines.

The other three contributors to have appeared in more than 400 issues of Mad are Sergio Aragonés, Dick DeBartolo, and Mort Drucker; Dave Berg, Paul Coker, and Frank Jacobs have each topped the 300 mark.

Among the irregular contributors with just a single Mad byline to their credit are Charles M. Schulz, Chevy Chase, Andy Griffith, Will Eisner, Kevin Smith, J. Fred Muggs, Boris Vallejo, Sir John Tenniel, Jean Shepherd, Winona Ryder, Jimmy Kimmel, Jason Alexander, Walt Kelly, Rep. Barney Frank, Tom Wolfe, Steve Allen, Jim Lee, Jules Feiffer, Donald Knuth, and Richard Nixon, who remains the only President credited with "writing" a Mad article.

When a comic strip satirizing England's royal family was reprinted in a Mad paperback, it was deemed necessary to rip out the page from 25,000 copies by hand before the book could be distributed in Great Britain.

Among other U.S. humor magazines that included some degree of comics art as well as text articles were former Mad editor Harvey Kurtzman's Trump, Humbug and Help!, as well as National Lampoon.

[100] In 1961, New York City doo-wop group The Dellwoods (recording then as the "Sweet Sickteens") had released a novelty single on RCA Victor, written by Norman Blagman and Sam Bobrick, "The Pretzel" (a satiric take on then-current dance songs such as "The Twist"), b/w "Agnes (The Teenage Russian Spy)".

(The Sweet Sickteens were Victor Buccellato (lead singer), Mike Ellis (tenor), Andy Ventura (tenor), Amadeo Tese (baritone), and Saul Zeskand (bass),[97][101][better source needed][102][better source needed] It's surprisingly straightforward teen-era rock 'n' roll...lyrically the songs do a decent job of matching Mad's off-kilter look at society... a few of these songs would be hard to differentiate as parody when compared to other records from the era.

This album also featured a song titled "It's a Gas", which punctuated an instrumental track with belches (these "vocals" being credited to Alfred E. Neuman), along with a saxophone break by an uncredited King Curtis).

Edition (which featured questions based around Time-Warner properties, including WB films and TV shows, the Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies cartoons (and follow-up projects from Warner Bros.

Produced by Kevin Shinick and Mark Marek,[116] the series was composed of animated shorts and sketches lampooning current television shows, films, games and other aspects of popular culture, in a similar manner to the adult stop-motion animated sketch comedy Robot Chicken (of which Shinick was formerly a writer and is currently a recurring voice actor); in fact, Robot Chicken co-creator Seth Green occasionally provided voices on Mad as well.