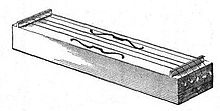

The Eolian Harp

It is one of the early conversation poems and discusses Coleridge's anticipation of a marriage with Sara Fricker along with the pleasure of conjugal love.

And watch the clouds, that late were rich with light, Slow saddening round, and mark the star of eve Serenely brilliant (such should Wisdom be) Shine opposite!

[9] As the poem continues, objects are described as if they were women being pursued:[10] And that simplest Lute, Placed length-ways in the clasping casement, hark!

How by the desultory breeze caress'd, Like some coy maid half yielding to her lover, It pours such sweet upbraiding, as must needs Tempt to repeat the wrong!

[9] Near the end of the poem, the narrator discusses pantheism before reproving himself for it soon after:[10] And what if all of animated nature Be but organic Harps diversely fram'd, That tremble into thought, as o'er them sweeps Plastic and vast, one intellectual breeze, At once the Soul of each, and God of all?

[11] As the poem was completed after Coleridge's marriage, the themes became similar to the ideas expressed in his Reflections on Having Left a Place of Retirement.

— My mind feels as if it ached to behold & know something great — something one & indivisible — and it is only in the faith of this that rocks or waterfalls, mountains or caverns give me the sense of sublimity or majesty!

[20] The poem discusses his understanding of nature within the concept of "One Life", an idea that is presented as a resulting from Coleridge's reflection on his experiences at Clevedon.

The "One Life" lines added to the 1817 edition interconnect the senses and also connects sensation and experience of the divine with the music of the Aeolian harp.

[21] Coleridge derived his early understanding from the works of Jakob Böhme, of which he wrote in a 4 July 1817 letter to Ludwig Tieck: "Before my visit to Germany in September, 1798, I had adopted (probably from Behmen's Aurora, which I had conjured over at School) the idea, that Sound was = Light under the praepotence of Gravitation, and Color = Gravitation under the praepotence of Light: and I have never seen reason to change my faith in this respect.

Coleridge's possible poetic influences include James Thomson's Ode on Aeolus's Harp, The Castle of Indolence, and Spring.

Arguments have been made for various possible philosophical influences, including: Joseph Priestley, George Berkeley and David Hartley;[24] Ralph Cudworth;[25] Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi and Moses Mendelssohn;[26] and Jakob Böhme.

[27] In Coleridge's copy of Kant's Critik der reinen Vernunft, he wrote: "The mind does not resemble an Eolian Harp, nor even a barrel-organ turned by a stream of water, conceive as many tunes mechanized in it as you like—but rather, as far as Objects are concerned, a violin, or other instrument of few strings yet vast compass, played on by a musician of Genius.

[32] Rosemary Ashton believes that the poem "shows an exact eye for natural detail combined with a sharp ear for rhythms both conversational and yet heightened into poetic form".