The Fens

The Fens or Fenlands in eastern England is a area of former marshland of low lying land supporting a rich ecology and numerous species.

There have been unintended consequences to this reclamation, as the land level has continued to sink and the dykes have been built higher to protect it from flooding.

It also designates the type of marsh typical of the area, which has neutral or alkaline water and relatively large quantities of dissolved minerals, but few other plant nutrients.

[4] The Fens have been referred to as the "Holy Land of the English" because of the former monasteries, now churches and cathedrals, of Crowland, Ely, Peterborough, Ramsey and Thorney.

Other significant settlements in the Fens include Boston, Downham Market, King’s Lynn, Mildenhall, March, Spalding, and Wisbech.

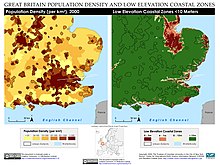

[5][6] The Fens are very low-lying compared with the chalk and limestone uplands that surround them – in most places no more than 10 metres (33 ft) above sea level.

Although one writer in the 17th century described the Fenland as entirely above sea level (in contrast to the Netherlands),[7] the area now includes the lowest land in the United Kingdom.

The largest of the fen-islands was the 23-square-mile (60 km2) Kimmeridge Clay island, on which the cathedral city of Ely was built: its highest point is 39 metres (128 ft) above mean sea level.

In this way, the medieval and early modern Fens stood in contrast to the rest of England, which was primarily an arable agricultural region.

The Lindsey Level, also known as the Black Sluice District, was first drained in 1639 and extends from the Glen and Bourne Eau to Swineshead and then across to Kirton.

The topography of the bed of the North Sea indicates that the rivers of the southern part of eastern England flowed into the Rhine, thence through the English Channel.

As the ice melted, the rising sea level drowned the lower lands, leading ultimately to the present coastline.

[12] These rising sea levels flooded the previously inland woodland of the Fenland basin; over the next few thousand years both saltwater and freshwater wetlands developed as a result.

Fenland water levels peaked in the Iron Age; earlier Bronze and Neolithic settlements were covered by peat deposits, and have only recently been found after periods of extensive droughts revealed them.

Though water levels rose once again in the early medieval period, by this time artificial banks protected the coastal settlements and the interior from further deposits of marine silts.

[12] The wetlands of the fens have historically included: Major areas for settlement were: In general, of the three principal soil types found in the Fenland today, the mineral-based silt resulted from the energetic marine environment of the creeks, the clay was deposited in tidal mud-flats and salt-marsh, while the peat grew in the fen and bog.

It is also recorded that peat was dug out of the East and West Lincolnshire fens in the 14th century and used to fire the salterns of Wrangle and Friskney.

[21] Internationally important sites include Flag Fen and Must Farm quarry Bronze Age settlement and Stonea Camp.

There may have been some drainage efforts during the Roman period, including the Car Dyke along the western edge of the Fenland between Peterborough and Lincolnshire, but most canals were constructed for transportation.

It is thought that some Iceni may have moved west into the Fens to avoid the Angles, who were migrating across the North Sea from Angeln (modern Schleswig) and settling what would become East Anglia.

Surrounded by water and marshes, the Fens provided a safe area that was easily defended and not particularly desirable to invading Anglo-Saxons.

It has been proposed that the names of West Walton, Walsoken and Walpole suggest the native British population, with the Wal- coming from the Old English walh, meaning "foreigner".

There is little agreement as to the exact dates of the establishment and demise of the forest, but it seems likely that the deforestation was connected with the Magna Carta or one of its early 13th-century restatements, though it may have been as late as 1240.

The forest would have affected the economies of the townships around it and it appears that the present Bourne Eau was constructed at the time of the deforestation, as the town seems to have joined in the general prosperity by about 1280.

Both cuts were named after the Fourth Earl of Bedford who, along with some gentlemen adventurers (venture capitalists), funded the construction and were rewarded with large grants of the resulting farmland.

The major part of the draining of the Fens was effected in the late 18th and early 19th century, again involving fierce local rioting and sabotage of the works.

[31] This, together with the shrinkage on its initial drying and the removal of soil by the wind, has meant that much of the Fens lies below high tide level.

As the highest parts of the drained fen are now only a few metres above mean sea level, only sizeable embankments of the rivers, and general flood defences, stop the land from being inundated.

[32] As of 2008, there are estimated to be 4,000 farms in the Fens involved in agriculture and horticulture, including arable, livestock, poultry, dairy, orchards, vegetables and ornamental plants and flowers.

It is the base of Great Britain Bandy Association[33] and in Littleport there is a project in place aiming at building an indoor stadium for ice sports.

alongside the River Great Ouse