The Garden of Earthly Delights

[4] Bosch renders the plant life in an unusual fashion, using uniformly gray tints, which make it difficult to determine whether the subjects are purely vegetal or perhaps include some mineral formations.

[14] Art historian Charles de Tolnay believed that, through the seductive gaze of Adam, the left panel already shows God's waning influence upon the newly created earth.

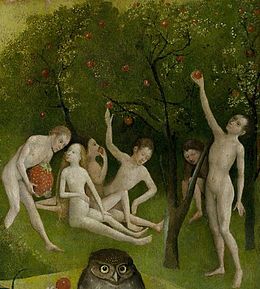

[13] According to Hans Belting, the three inner panels seek to broadly convey the Old Testament notion that, before the Fall, there was no defined boundary between good and evil; humanity in its innocence was unaware of consequence.

Belting observes that, although the creatures in the foreground are fantastical imaginings, many of the animals in the mid and background are drawn from contemporary travel literature, and here Bosch is appealing to "the knowledge of a humanistic and aristocratic readership".

[22] Erhard Reuwich's pictures for Bernhard von Breydenbach's 1486 Pilgrimages to the Holy Land were long thought to be the source for both the elephant and the giraffe, though more recent research indicates the mid-15th-century humanist scholar Cyriac of Ancona's travelogues served as Bosch's exposure to these exotic animals.

Gibson describes them as behaving "overtly and without shame," [29] while art historian Laurinda Dixon writes that the human figures exhibit "a certain adolescent sexual curiosity".

[17] Many of the numerous human figures revel in an innocent, self-absorbed joy as they engage in a wide range of activities; some appear to enjoy sensory pleasures, others play unselfconsciously in the water, and yet others cavort in meadows with a variety of animals, seemingly at one with nature.

Art historian Patrik Reuterswärd, for example, posits that they may be seen as "the noble savage" who represents "an imagined alternative to our civilized life", imbuing the panel with "a more clear-cut primitivistic note".

[31] Four women carry cherry-like fruits on their heads, perhaps a symbol of pride at the time, as has been deduced from the contemporaneous saying: "Don't eat cherries with great lords—they'll throw the pits in your face.

"[15] Fraenger titled his chapter on the high background "The Ascent to Heaven" and wrote that the airborne figures were likely intended as a link between "what is above" and "what is below," just as the left and right-hand panels represent "what was" and "what will be.

[42] In a single, densely detailed scene, the viewer is made witness to cities on fire in the background; war, torture chambers, infernal taverns, and demons in the midground, and mutated animals feeding on human flesh in the foreground.

A grey figure in a hood bearing an arrow jammed between his buttocks climbs a ladder into the tree-man's central cavity, where nude men sit in a tavern-like setting.

[47] Belting proposed that the tree-man's face is a self-portrait, citing the figure's "expression of irony and the slightly sideways gaze [which would] then constitute the signature of an artist who claimed a bizarre pictorial world for his own personal imagination".

They represent seas, skies, woods, meadows, and many other things, such as people crawling out of a shell, others that bring forth birds, men and women, white and blacks doing various activities and poses.

[63] Upon the death of Henry III, the painting passed into the hands of his nephew William the Silent, the founder of the House of Orange-Nassau and leader of the Dutch Revolt against Spain.

A contemporaneous description of the transfer records the gift on 8 July 1593[52] of a "painting in oils, with two wings depicting the variety of the world, illustrated with grotesqueries by Hieronymus Bosch, known as 'Del Madroño'".

Art historian Erwin Panofsky wrote in 1953, "In spite of all the ingenious, erudite and in part extremely useful research devoted to the task of "decoding Jerome Bosch," I cannot help feeling that the real secret of his magnificent nightmares and daydreams has still to be disclosed.

Glum remarked on the triptych's similarity of tone with Erasmus's view that theologians "explain (to suit themselves) the most difficult mysteries ... is it a possible proposition: God the Father hates the Son?

[59] Analyses based on symbolic systems ranging from the alchemical, astrological, and heretical to the folkloric and subconscious have all attempted to explain the complex objects and ideas presented in the work.

"[85] De Tolnay wrote that the center panel represents "the nightmare of humanity," where "the artist's purpose above all is to show the evil consequences of sensual pleasure and to stress its ephemeral character.

Although according to the art historian Walter Bosing, each of these works is rendered in a manner that is difficult to believe "Bosch intended to condemn what he painted with such visually enchanting forms and colors."

[87] In 1947, Wilhelm Fränger argued that the triptych's center panel portrays a joyous world when mankind will experience a rebirth of the innocence enjoyed by Adam and Eve before their fall.

This radical group, active in the area of the Rhine and the Netherlands, strove for a form of spirituality immune from sin even in the flesh and imbued the concept of lust with a paradisical innocence.

Writer Carl Linfert also senses the joyfulness of the people in the center panel but rejects Fränger's assertion that the painting is a "doctrinaire" work espousing the "guiltless sexuality" of the Adamite sect.

It corroborates - as a starting point for the reading of this triptych - the contemporary interpretation of Jean Wirth, followed by Frédéric Elsig and Hans Belting: that of the vision of the reality of an infernal present.

This inversion is said to have been deliberately created by Hieronymus Bosch to blur the lines of his pictorial manifesto, which was originally so heterodox and subversive, not to say heretical, in the eyes of the Roman Catholic Church of his time.

Bruegel's Mad Meg depicts a peasant woman leading an army of women to pillage Hell, while his The Triumph of Death (c. 1562) echoes the monstrous Hellscape of The Garden, and utilizes, according to the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, the same "unbridled imagination and the fascinating colours".

[99] While the Italian court painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo (c. 1527–1593) did not create Hellscapes, he painted a body of strange and "fantastic" vegetable portraits—generally heads of people composed of plants, roots, webs and various other organic matter.

Miró's The Tilled Field contains several parallels to Bosch's Garden: similar flocks of birds; pools from which living creatures emerge; and oversize disembodied ears all echo the Dutch master's work.

[101] Dalí's 1929 The Great Masturbator is similar to an image on the right side of the left panel of Bosch's Garden, composed of rocks, bushes and little animals resembling a face with a prominent nose and long eyelashes.