The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money

Keynes denied that an economy would automatically adapt to provide full employment even in equilibrium, and believed that the volatile and ungovernable psychology of markets would lead to periodic booms and crises.

It introduced the concepts of the consumption function, the principle of effective demand and liquidity preference, and gave new prominence to the multiplier and the marginal efficiency of capital.

The object of such a title is to contrast the character of my arguments and conclusions with those of the classical theory of the subject, upon which I was brought up and which dominates the economic thought, both practical and theoretical, of the governing and academic classes of this generation, as it has for a hundred years past.

Keynes on the other hand viewed the market distortions as part of the economic fabric and advocated different policy measures which (as a separate consideration) had social consequences which he personally found congenial and which he expected his readers to see in the same light.

The economy needs to find its way to an equilibrium in which no more money is being saved than will be invested, and this can be accomplished by contraction of income and a consequent reduction in the level of employment.

Long-term expectation 'is concerned with what the entrepreneur can hope to earn in the shape of future returns if he (sic) purchases (or perhaps manufactures) "finished" output as an addition to his capital equipment.

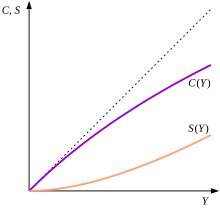

Book III of the General Theory is given over to the propensity to consume, which is introduced in Chapter 8 as the desired level of expenditure on consumption (for an individual or aggregated over an economy).

Keynes discusses the possible influence of the interest rate r on the relative attractiveness of saving and consumption, but regards it as 'complex and uncertain' and leaves it out as a parameter.

In his provocation Keynes argues that "If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the banknotes up again" (...), there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is.

But the position is serious when enterprise becomes the bubble on a whirlpool of speculation.’ He suggests that: ‘The introduction of a substantial Government transfer tax on all transactions might prove the most serviceable reform available, with a view to mitigating the predominance of speculation over enterprise in the United States.’[13] To account for the apparent ‘foolishness’ on which economic progress seemed to rely, Keynes suggests that:[14] Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as a result of animal spirits – of a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.Keynes proposes two theories of liquidity preference (i.e. the demand for money): the first as a theory of interest in Chapter 13 and the second as a correction in Chapter 15.

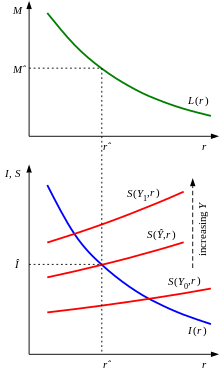

His arguments offer ample scope for criticism, but his final conclusion is that liquidity preference is a function mainly of income and the interest rate.

The structure of Keynes's expression plays no part in his subsequent theory, so it does no harm to follow Hicks by writing liquidity preference simply as L(Y,r).

In Chapter 14 Keynes contrasts the classical theory of interest with his own, and in making the comparison he shows how his system can be applied to explain all the principal economic unknowns from the facts he takes as given.

The first equation asserts that the reigning rate of interest r̂ is determined from the amount of money in circulation M̂ through the liquidity preference function and the assumption that L(r̂)=M̂.

And finally, since Keynes's discussion takes place in Chapter 14, it precedes the modification which makes liquidity preference depend on income as well as on the rate of interest.

If we wish to examine the classical system our task is made easier if we assume that the effect of the interest rate on the velocity of circulation is small enough to be ignored.

Thus if the animal spirits are dimmed and spontaneous optimism falters, leaving us to depend on nothing but a mathematical expectation, enterprise will fade and die.

[32] Keynes considers[33] speculators to be concerned... ...not with what an investment is really worth to a man who buys it 'for keeps', but with what the market will value it at, under the influence of mass psychology, three months or a year hence...

His task is made easier by a less restrictive (but nonetheless crude) assumption concerning wage behaviour: let us simplify our assumptions still further, and assume... that the factors of production... are content with the same money-wage so long as there is a surplus of them unemployed... ; whilst as soon as full employment is reached, it will thenceforward be the wage-unit and prices which will increase in exact proportion to the increase in effective demand.

[34]Keynes's theory of the trade cycle is based on 'a cyclical change in the marginal efficiency of capital' induced by 'the uncontrollable and disobedient psychology of the business world' (pp.

There are reasons, given firstly by the length of life of durable assets... and secondly by the carrying-costs of surplus stocks, why the duration of the downward movement should have an order of magnitude... between, let us say, three and five years.

Lerner pointed out in the 40s that it was optimistic to hope that the workforce would be content with fixed wages in the presence of rising prices, and proposed a modification to Keynes's model.

Keynes' object was to simplify the process of circulating drafts; and eventually to secure good sales by fixing the retail price lower than would Macmillan & Co.[42]The advantages of self-publication can be seen from Étienne Mantoux's review: When he published The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money last year at the sensational price of 5 shillings, J. M. Keynes perhaps meant to express a wish for the broadest and earliest possible dissemination of his new ideas.

[47] In autumn 1933 Keynes's lectures were much closer to the General Theory, including the consumption function, effective demand, and a statement of 'the inability of workers to bargain for a market-clearing real wage in a monetary economy'.

[57] Keynes did not set out a detailed policy program in The General Theory, but he went on in practice to place great emphasis on the reduction of long-term interest rates[58] and the reform of the international monetary system[59] as structural measures needed to encourage both investment and consumption by the private sector.

Paul Samuelson said that the General Theory "caught most economists under the age of 35 with the unexpected virulence of a disease first attacking and decimating an isolated tribe of South Sea islanders.

Prior to the financial crises of 2007-9, the majority new consensus view, still found in most current text-books and taught in all universities, was New Keynesian economics, which (in contrast to Keynes) accepts the neoclassical concept of long-run equilibrium but allows a role for aggregate demand in the short run.

The minority view is represented by post-Keynesian economists, all of whom accept Keynes's fundamental critique of the neoclassical concept of long-run equilibrium, and some of whom think The General Theory has yet to be properly understood and repays further study.

Post-Keynesians argue that the neoclassical Keynesian model is completely distorting and misinterpreting Keynes' original meaning, at least in so far as it largely rests on an assumed long-term equilibrium.

Although few modern economists would disagree with the need for at least some intervention, policies such as labour market flexibility are underpinned by the neoclassical notion of equilibrium in the long run.