American Indian Movement

These issues have included treaty rights, high rates of unemployment, the lack of American Indian subjects in education, and the preservation of Indigenous cultures.

[8] Public documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) reveal advanced coordination occurred between federal Bureau of Indian Affairs staff and the authors of a twenty-point proposal.

In the decades since AIM's founding, the group has led protests advocating indigenous American interests, inspired cultural renewal, monitored police activities, and coordinated employment programs in cities and in rural reservation communities across the United States.

A U.S. government policy directive from 1940 to the early 1960s, under multiple executive administrations (both Democrat and Republican), led to the establishment of uranium mining operations across Navajo tribal lands.

[10] As a result, the Navajo people believe that the federal government has violated the Treaty of 1868, which assigned the Bureau of Indian Affairs to provide services that safeguard their health.

During ceremonies on Thanksgiving Day 1970 to commemorate the 350th anniversary of the Pilgrims' landing at Plymouth Rock, an AIM group seized the replica of the Mayflower in Boston.

This huge sculpture was created on a mountain long considered sacred by the Lakota, and the associated land in the Black Hills of South Dakota was taken by the federal government after gold was discovered there.

This area was originally within the Great Sioux Reservation as created by the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, which covered most of present-day South Dakota west of the Missouri River.

[15] Also in 1971, AIM began to highlight and protest problems with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), which administered programs and land trusts for Native Americans.

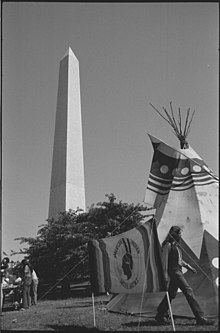

[16] In 1972, activists marched across the country on the "Trail of Broken Treaties" and took over the Department of Interior headquarters, including the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), occupying it for several days and allegedly doing millions of dollars in damage.

[25] The purpose of this 3,200-mile (5,100 km) walk was to educate people about the government's continuing threat to tribal sovereignty; it rallied thousands representing many Indian nations throughout the United States and Canada.

Over the next week, they held rallies at various locations to address issues, including the series of proposed federal bills, American Indian political prisoners, forced relocation at Big Mountain, and the Navajo Nation.

[27] Thirty years later, AIM led the Longest Walk 2, which covered 8,200 miles (13,200 km) starting from the San Francisco Bay area and arriving in Washington, D.C. in July 2008.

They converged at the mountain in order to protest the illegal seizure of the Sioux Nation's sacred Black Hills in 1877 by the United States federal government, in violation of its earlier 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

[40] In 1972, Raymond Yellow Thunder, a 51-year-old Oglala Lakota from Pine Ridge Reservation, was murdered in Gordon, Nebraska, by two brothers, Leslie and Melvin Hare, younger white men.

Members of AIM went to Gordon to protest the sentences, arguing they were part of a pattern of law enforcement that did not provide justice to Native Americans in counties and communities bordering Indian reservations.

The talks were not successful, and tempers rose over the police treatment; AIM activists caused $2 million in damages by attacking and burning the Custer Chamber of Commerce building, the courthouse, and two patrol cars.

[39] In addition to the problems of violence in the border towns, many traditional people at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation were unhappy with the government of Richard Wilson, elected in 1972.

The Oglala Lakota demanded a revival of treaty negotiations to begin to correct relations with the federal government, the respect of their sovereignty, and the removal of Wilson from office.

The Academy Awards ceremony was held in Hollywood, where the actor Marlon Brando, a supporter of AIM, asked Sacheen Littlefeather to speak at the Oscars on his behalf.

Littlefeather arrived in full Apache regalia and read his statement that, owing to the "poor treatment of Native Americans in the film industry," Brando would not accept the award.

On June 26, 1975, two FBI agents, Jack Coler and Ronald Williams, were on the Pine Ridge Reservation searching for someone who was wanted for questioning which was related to an assault and a robbery which was committed against two ranch hands.

Later, reinforcements arrived, and Joe Stuntz, an AIM member who had taken part in the shootout, was fatally shot, and when he was found dead, he was wearing Coler's FBI jacket.

After the coroner failed to find the bullet hole in Aquash's head, the FBI severed both of her hands and sent them to Washington, D.C., allegedly for identification purposes, then buried her as a Jane Doe.

This position was controversial among other left-wing, indigenous rights groups and Central American solidarity organizations in the United States who opposed Contra activities and supported the Sandinista movement.

It also condemned certain named individuals (such as Brooke Medicine Eagle, Wallace Black Elk, and Sun Bear and his tribe) and criticized specific organizations such as Vision Quest, Inc.

The Tokama Institute, a division of the AIOIC, is focused on helping American Indians acquire the foundational skills and knowledge in order to obtain a successful career.

The autonomous chapters reject the assertions of central control by the Minneapolis group as contrary both to indigenous political traditions and to the original philosophy of AIM.

[71] At a press conference in Denver, Colorado, on 3 November 1999, Russell Means accused Vernon Bellecourt of having ordered the execution of Anna Mae Aquash in 1975.

The "highest-ranking" woman in AIM at the time, she had been shot execution style in mid-December 1975 and left in a far corner of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation after having been kidnapped from Denver, Colorado, and interrogated in Rapid City, South Dakota, as a possible FBI informant.