Os Lusíadas

[2] Written in Homeric fashion, the poem focuses mainly on a fantastic interpretation of the Portuguese voyages of discovery during the 15th and 16th centuries.

The most important part of Os Lusíadas, the arrival in India, was placed at the point in the poem that divides the work according to the golden section at the beginning of Canto VII.

The initial strophes of Jupiter's speech in the Concílio dos Deuses Olímpicos (Council of the Olympian Gods), which open the narrative part, highlight the laudatory orientation of the author.

In contrast to the style of lyric poetry, or "humble verse" ("verso humilde"), he is thinking about this exciting tone of oratory.

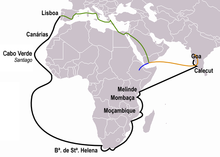

Many times, da Gama bursts into oration at challenging moments: in Mombasa (Canto II), on the appearance of Adamastor, and in the middle of the terror of the storm.

Just as the gods had divided loyalties during the voyages of Odysseus and Aeneas, here Venus, who favors the Portuguese, is opposed by Bacchus, who is here associated with the east and resents the encroachment on his territory.

After an appeal by the poet to Calliope, the Greek muse of epic poetry, Vasco da Gama begins to narrate the history of Portugal.

The narrative of the Crisis of 1383–85, which focuses mainly on the figure of Nuno Álvares Pereira and the Battle of Aljubarrota, is followed by the events of the reigns of Dom João II, especially those related to expansion into Africa.

Then, while the sailors are listening to Fernão Veloso telling the legendary and chivalrous episode of Os Doze de Inglaterra (The Twelve Men of England), a storm strikes.

Vasco da Gama, seeing the near destruction of his caravels, prays to his own God, but it is Venus who helps the Portuguese by sending the Nymphs to seduce the winds and calm them down.

After condemning some of the other nations of Europe (who in his opinion fail to live up to Christian ideals), the poet tells of the Portuguese fleet reaching the Indian city of Calicut.

The Muslims plot to detain the Portuguese until the annual trading fleet from Mecca can arrive to attack them, but Monçaide tells da Gama of the conspiracy, and the ships escape from Calicut.

To reward the explorers for their efforts, Venus prepares an island for them to rest on and asks her son Cupid to inspire Nereids with desire for them.

During a sumptuous feast on the Isle of Love, Tethys, who is now the lover of da Gama, prophecies the future of Portuguese exploration and conquest.

The gods of the four corners of the world are reunited to talk about "the future matters of the East" ("as cousas futuras do Oriente"); in fact, what they are going to decide is whether the Portuguese will be allowed to reach India and what will happen next.

The gods are described by Jupiter as residents of the "shiny, / starry Pole and bright Seat" ("luzente, estelífero Pólo e claro Assento"); this shiny, starry Pole and bright Seat or Olympus had already been described before as "luminous"; the Gods walk on the "beautiful crystalline sky" ("cristalino céu fermoso"), to the Milky Way.

The vigorous theophany that the first part describes is in the following verses: "Chill the flesh and the hairs/ to me and all [the others] only by listening and seeing him" ("Arrepiam-se as carnes e os cabelos / a mi e a todos só de ouvi-lo e vê-lo").

The "strange Colossus" ("estranhíssimo Colosso"): "Rude son of the Earth" ("Filho aspérrimo da Terra") is described as having: "huge stature", "squalid beard", "earthy colour", "full of earth and crinkly of hairs / blacken the mouth, yellow the teeth" ("disforme estatura", "barba esquálida", "cor terrena", "cheios de terra e crespos os cabelos / a boca negra, os dentes, amarelos").

Such emphasis on the appearance of Adamastor is intended to contrast with the preceding scenery, which was expressed as: "seas of the South" ("mares do Sul"): "(...) / the winds blowing favourably / when one night, being careless/ watching in the cutting bow, / (...)" ("(...) / prosperamente os ventos assoprando, / quando hua noite, estando descuidados / na cortadora proa vigiando, / (...)").

The final marine eclogue conforms to a pattern that is common to many of Camões' lyrical compositions: falling in love, forced separation, grieving over the frustrated dream.

The allegory in the second part of Canto IX sees Camões describing the scene between the sailors – whom the Nymphs were expecting – prepared by Venus.

Que as Ninfas do Oceano, tão fermosas, Tétis e a Ilha angélica pintada, Outra cousa não é que as deleitosas Honras que a vida fazem sublimada That the Nymphs of the Ocean, so beautiful, Tethys and the angelic painted Island, Are none other than the delightful Honours that render life sublime The Canto is ended with the poet communicating to the reader:

Impossibilidades não façais, Que quem quis sempre pôde: e numerados Sereis entre os heróis esclarecidos E nesta Ilha de Vénus recebidos.

In Canto X, before the sailors return home the Siren invites Gama to the spectacle of the Machine of the World (Máquina do Mundo) with these words:

Faz-te mercê, barão, a sapiência Suprema de, cos olhos corporais, veres o que não pode a vã ciência dos errados e míseros mortais Your lordship's wish is now fulfilled to share the supreme knowledge; you with corporeal eyes may see what the vain science of erring and miserable mortals cannot The Machine of the World is presented as the spectacle unique, divine, seen by "corporeal eyes".

In the words of literary historian António José Saraiva, "it is one of the supreme successes of Camões", "the spheres are transparent, luminous, all of them are seen at the same time with equal clarity; they move, and the movement is perceptible, although the visible surface is always the same.