Siren (mythology)

Sirens continued to be used as a symbol of the dangerous temptation embodied by women regularly throughout Christian art of the medieval era.

[8][9] The circumstances leading to the commingling involve the treatment of sirens in the medieval Physiologus and bestiaries, both iconographically,[10] as well as textually in translations from Latin to vulgar languages,[a][11] as described below.

[8] The sirens are described as mermaids or "tritonesses" in examples dating to the 3rd century BC, including an earthenware bowl found in Athens[20][22] and a terracotta oil lamp possibly from the Roman period.

The siren was depicted as a half-woman and half-fish mermaid in the 9th century Berne Physiologus,[25] as an early example, but continued to be illustrated with both bird-like parts (wings, clawed feet) and fish-like tail.

One of the crew, however, the sharp-eared hero Butes, heard the song and leapt into the sea, but he was caught up and carried safely away by the goddess Aphrodite.

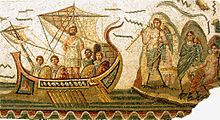

[51] Some post-Homeric authors state that the sirens were fated to die if someone heard their singing and escaped them, and that after Odysseus passed by they therefore flung themselves into the water and perished.

[52] The first-century Roman historian Pliny the Elder discounted sirens as a pure fable, "although Dinon, the father of Clearchus, a celebrated writer, asserts that they exist in India, and that they charm men by their song, and, having first lulled them to sleep, tear them to pieces.

"[53] Statues of sirens in a funerary context are attested since the classical era, in mainland Greece, as well as Asia Minor and Magna Graecia.

The so-called "Siren of Canosa"—Canosa di Puglia is a site in Apulia that was part of Magna Graecia—was said to accompany the dead among grave goods in a burial.

The term "siren song" refers to an appeal that is hard to resist but that, if heeded, will lead to a bad conclusion.

Later writers have implied that the sirens ate humans, based on Circe's description of them "lolling there in their meadow, round them heaps of corpses rotting away, rags of skin shriveling on their bones.

"[56] The siren song is a promise to Odysseus of mantic truths; with a false promise that he will live to tell them, they sing,Once he hears to his heart's content, sails on, a wiser man.We know all the pains that the Greeks and Trojans once enduredon the spreading plain of Troy when the gods willed it so—all that comes to pass on the fertile earth, we know it all!

It has been suggested that, with their feathers stolen, their divine nature kept them alive, but unable to provide food for their visitors, who starved to death by refusing to leave.

[59] According to the ancient Hebrew Book of Enoch, the women who were led astray by the fallen angels will be turned into sirens.

[60] By the fourth century, when pagan beliefs were overtaken by Christianity, the belief in literal sirens was discouraged[dubious – discuss] Saint Jerome, who produced the Latin Vulgate version of the bible, used the word sirens to translate Hebrew tannīm ("jackals") in the Book of Isaiah 13:22, and also to translate a word for "owls" in the Book of Jeremiah 50:39.

The siren is allegorically described as a beautiful courtesan or prostitute, who sings pleasant melodies to men, and is the symbolic vice of Pleasure in the preaching of Clement of Alexandria (2nd century).

[74] The siren was illustrated as a woman-fish (mermaid) in the Bern Physiologus dated to the mid-9th century, even though this contradicted the accompanying text which described it as avian.

[25] An English-made Latin bestiary dated 1220–1250 also depicted a group of sirens as mermaids with fishtails swimming in the sea, even though the text stated they resembled winged fowl (volatilis habet figuram) down to their feet.

[96] Thus the comb and mirror, which are now emblematic of mermaids across Europe, derive from the bestiaries that describe the siren as a vain creature requiring those accoutrements.

In Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136), Brutus of Troy encounters sirens at the Pillars of Hercules on his way to Britain to fulfil a prophecy that he will establish an empire there.

Seen as a creature who could control a man's reason, female singers became associated with the mythological figure of the siren, who usually took a half-human, half-animal form somewhere on the cusp between nature and culture.

Hence it is probable, that in ancient times there may have been excellent singers, but of corrupt morals, on the coast of Sicily, who by seducing voyagers, gave rise to this fable.

"[113] John Lemprière in his Classical Dictionary (1827) wrote, "Some suppose that the sirens were several lascivious women in Sicily, who prostituted themselves to strangers, and made them forget their pursuits while drowned in unlawful pleasures.

[114] This distinguished critic makes the sirens to have been excellent singers, and divesting the fables respecting them of all their terrific features, he supposes that by the charms of music and song, they detained travellers, and made them altogether forgetful of their native land.

According to Debussy, "'Sirènes' depicts the sea and its countless rhythms and presently, amongst the waves silvered by the moonlight, is heard the mysterious song of the Sirens as they laugh and pass on".