The Thing (1982 film)

Based on the 1938 John W. Campbell Jr. novella Who Goes There?, it tells the story of a group of American researchers in Antarctica who encounter the eponymous "Thing", an extraterrestrial life-form that assimilates, then imitates, other organisms.

Filming lasted roughly twelve weeks, beginning in August 1981, and took place on refrigerated sets in Los Angeles as well as in Juneau, Alaska, and Stewart, British Columbia.

the Extra-Terrestrial, which offered an optimistic view of alien visitation; a summer that had been filled with successful science fiction and fantasy films; and an audience living through a recession, diametrically opposed to The Thing's nihilistic and bleak tone.

[14][9] Stunt coordinator Dick Warlock also made a number of cameos in the film, most notably in an off-screen appearance as the shadow on the wall during the scene where the Dog-Thing enters one of the researcher's living quarters.

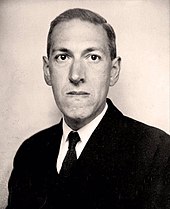

It had been loosely adapted once before in Howard Hawks' and Christian Nyby's 1951 film The Thing from Another World, but Foster and Turman wanted to develop a project that stuck more closely to the source material.

[19] Universal in turn acquired the rights to remake the film from Stark, resulting in him being given an executive producer credit on all print advertisements, posters, television commercials, and studio press material.

The producers discussed various replacements including Walter Hill, Sam Peckinpah and Michael Ritchie, but the development of El Diablo was not as imminent as Carpenter believed, and he remained with The Thing.

[23][33] Lancaster wrote this ending, which eschews a The Twilight Zone-style twist or the destruction of the monster, as he wanted to instead have an ambiguous moment between the pair, of trust and mistrust, fear and relief.

[37][38] Carpenter wanted to keep his options open for the lead R.J. MacReady, and discussions with the studio considered Christopher Walken, Jeff Bridges, and Nick Nolte, who were either unavailable or declined, and Sam Shepard, who showed interest but was never pursued.

[26] Geoffrey Holder, Carl Weathers, and Bernie Casey were considered for the role of mechanic Childs, and Carpenter also looked at Isaac Hayes, having worked with him on Escape from New York.

[40] The Thing was David's first significant film role, and coming from a theater background, he had to learn on set how to hold himself back and not show every emotion his character was feeling, with guidance from Richard Masur and Donald Moffat in particular.

As the character has some comedic moments, Universal brought in comedians Jay Leno, Garry Shandling, and Charles Fleischer, among others, but opted to go with actor David Clennon, who was better suited to play the dramatic elements.

[46] Cundey pushed for the use of anamorphic format aspect ratio, believing that it allowed for placing several actors in an environment, and making use of the scenic vistas available, while still creating a sense of confinement within the image.

[23][56] Universal executive Sidney Sheinberg disliked the ending's nihilism and, according to Carpenter, said, "Think about how the audience will react if we see the [Thing] die with a giant orchestra playing".

The reaction from the exclusively male exhibitors was generally positive, and Universal executive Robert Rehme told Cohen that the studio was counting on The Thing's success, as they expected E.T.

[75] The response to public pre-screenings of The Thing resulted in the studio changing the somber, black-and-white advertising approved by the producers to a color image of a person with a glowing face.

[86] Starlog's Alan Spencer called it a "cold and sterile" horror movie attempting to cash in on the genre audience, against the "optimism of E.T., the reassuring return of Star Trek II, the technical perfection of Tron, and the sheer integrity of Blade Runner".

[88] Roger Ebert considered the film to be scary, but offering nothing original beyond the special effects,[92] while The New York Times' Vincent Canby said it was entertaining only if the viewer needed to see spider-legged heads and dog autopsies.

[96] The review noted that the narrative "seems little more than an excuse for the various set-pieces of special effects and Russell's hero is no more than a cypher compared to Tobey's rounded character in Howard Hawks' The Thing".

[109] Sidney Sheinberg edited a version of the film for network television broadcast, which added narration and a different ending, where the Thing imitates a dog and escapes the ruined camp.

[127] A scene in which MacReady, Bennings, and Childs chase infected dogs out into the snow is included,[128] and Nauls' disappearance is explained: Cornered by the Blair-Thing, he chooses suicide over assimilation.

Diabolique's Daniel Clarkson Fisher notes that preferring annihilation to defeat is a recurring motif, both in MacReady's destruction of the chess computer after being checkmated and his vow to destroy the Thing even at the expense of the team.

[141][146] Slant Magazine's John Lingsan said the men display a level of post-Vietnam War (1955–1975) "fatigued counterculturalism" – the rejection of conventional social norms, each defined by their own eccentricities.

[37][159][160] John Kenneth Muir called it "Carpenter's most accomplished and underrated directorial effort",[161] and critic Matt Zoller Seitz said it "is one of the greatest and most elegantly constructed B-movies ever made".

[162] Trace Thurman described it as one of the best films ever,[163] and in 2008, Empire magazine selected it as one of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time,[164] at number 289, calling it "a peerless masterpiece of relentless suspense, retina-wrecking visual excess and outright, nihilistic terror".

The site's critics consensus reads: "Grimmer and more terrifying than the 1950s take, John Carpenter's The Thing is a tense sci-fi thriller rife with compelling tension and some remarkable make-up effects.

"[189] It has been referred to in a variety of media, from television (including The X-Files, Futurama, and Stranger Things) to games (Resident Evil 4, Tomb Raider III,[163] Icewind Dale: Rime of the Frostmaiden,[190] and Among Us[191]), and films (The Faculty, Slither, and The Mist).

[163] Several filmmakers have spoken of their appreciation for The Thing or cited its influence on their own work, including Guillermo del Toro,[192] James DeMonaco,[193] J. J. Abrams,[194] Neill Blomkamp,[195] David Robert Mitchell,[196] Rob Hardy,[197] Steven S. DeKnight,[198] and Quentin Tarantino.

[200] The 2015 Tarantino film The Hateful Eight takes numerous cues from The Thing, from featuring Russell in a starring role, to replicating themes of paranoia and mistrust between characters restricted to a single location, and even duplicating certain angles and layouts used by Carpenter and Cundey.

[219] Although released years apart, and unrelated in terms of plot, characters, crew, or even production studios, Carpenter considers The Thing to be the first installment in his "Apocalypse Trilogy", a series of films based around cosmic horror, entities unknown to man, that are threats to both human life and the sense of self.