History of the United Kingdom during the First World War

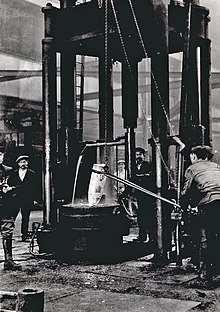

By adapting to the changing demographics of the workforce (or the "dilution of labour", as it was termed), war-related industries grew rapidly, and production increased, as concessions were quickly made to trade unions.

Research conducted for the centenary of the conflict suggested that the modern public tended to view British involvement in the First World War in a positive light with the exception of believing that the performance of generals was inadequate.

However, the large antiwar element among Liberals would support the war to honour the 1839 treaty regarding guarantees of Belgian neutrality, so that, rather than France, was the public reason given.

[5] For the first time, the government could react quickly, without endless bureaucracy to tie it down, and with up-to-date statistics on such matters as the state of the merchant navy and farm production.

On 21 March 1918 Germany launched a full scale Spring Offensive against the British and French lines, hoping for victory on the battlefield before United States troops arrived in large numbers.

Lloyd George found half a million soldiers and rushed them to France, asked American President Woodrow Wilson for immediate help, and agreed to the appointment of the French General Foch as commander in chief on the Western Front, so that Allied forces could be coordinated to handle the German offensive.

[32][33] On 7 May 1918, a senior army officer on active duty, Major-General Sir Frederick Maurice, prompted a second crisis when he went public with allegations that Lloyd George had lied to Parliament about troop numbers in France.

[51][52] The Prince of Wales – the future Edward VIII – was keen to participate in the war but the government refused to allow it, citing the immense harm that would occur if the heir to the throne were captured.

[77] In view of their inferior numbers and firepower, the Germans devised a plan to draw part of the British fleet into a trap and put it into effect at Jutland in May 1916, but the result was inconclusive.

[77] At the start of the war, the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), commanded by David Henderson, was sent to France and was first used for aerial spotting in September 1914, but only became efficient when they perfected the use of wireless communication at Aubers Ridge on 9 May 1915.

Because of its potential for the 'devastation of enemy lands and the destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale', he recommended a new air service be formed that would be on a level with the army and navy.

[99] Propaganda supporting the British war effort often used these raids to their advantage: one recruitment poster claimed: "It is far better to face the bullets than to be killed at home by a bomb" (see image).

The reaction from the public, however, was mixed; whilst 10,000 visited Scarborough to view the damage there, London theatres reported having fewer visitors during periods of "Zeppelin weather"—dark, fine nights.

Until its abolition in 1917, the department published 300 books and pamphlets in 21 languages, distributed over 4,000 propaganda photographs every week, and circulated maps, cartoons, and lantern slides to the media.

For these reasons, it has been concluded that censorship, which at its height suppressed only socialist journals (and briefly the right wing The Globe) had less effect on the British press than the reductions in advertising revenues and cost increases which they also faced during the war.

[115] The 1916 British film The Battle of the Somme, by two official cinematographers, Geoffrey Malins and John McDowell, combined documentary and propaganda, seeking to give the public an impression of what trench warfare was like.

[122] With the City of London the world's financial capital, it was possible to handle finances smoothly; in all Britain spent 4 million pounds everyday on the war effort.

[134] Bread was subsidised from September that year; prompted by local authorities taking matters into their own hands, compulsory rationing was introduced in stages between December 1917 and February 1918,[63] as Britain's supply of wheat stores decreased to just six weeks worth.

[146][147][148] It was only as late as December 1917 that a War Cabinet Committee on Manpower was established, and the British government refrained from introducing compulsory labour direction (though 388 men were moved as part of the voluntary National Service Scheme).

[8] Women both found work in the munitions factories (as "munitionettes") despite initial trade union opposition, which directly helped the war effort, but also in the Civil Service, where they took men's jobs, releasing them for the front.

This taken together with the fact that only 23 percent of women in the munitions industry were actually doing men's jobs, would limit substantially the overall impact of the war on the long-term prospects of the working woman.

[8] When the government targeted women early in the war focused on extending their existing roles – helping with Belgian refugees, for example—but also on improving recruitment rates amongst men.

The enfranchisement of this latter group was accepted as recognition of the contribution made by women defence workers,[157] though the actual feelings of members of parliament (MPs) at the time is questioned.

He also argues that:[160] This homogeneity was strengthened rather than weakened by a marked parochialism and regionalism, of which the Scots and Welsh identities were only the most prominent, with most people looking to their local rather than national leaders, including local business, religious, and trade union representatives.The War had a profound influence upon rural areas, as the U-boat blockade required the government to take full control of the food chain, as well as agricultural labour.

[166] Adrian Gregory points out that the Welsh coal miners, while officially supporting the war effort, refused the government request to cut short their holiday time.

[181] The war was a major economic catastrophe as Britain went from being the world's largest overseas investor to being its biggest debtor, with interest payments consuming around 40 percent of the national budget.

Battles such as Gallipoli for Australia and New Zealand,[186] and Vimy Ridge for Canada led to increased national pride and a greater reluctance to remain subordinate to London.

[188] The colonies of Germany and the Ottoman Empire were redistributed to the Allies (including Australia, New Zealand and South Africa) as League of Nations mandates, with Britain gaining control of Palestine and Transjordan, Iraq, parts of Cameroon and Togo, and Tanganyika.

Historian A. J. P. Taylor argued, "The Somme set the picture by which future generations saw the First World War: brave helpless soldiers; blundering obstinate generals; nothing achieved.

[192] Polling conducted by YouGov in 2014 suggested that 58% of modern British adults believed the Central powers were primarily responsible for the outbreak of the First World War, 3% the Triple Entente (the major countries in each group were listed), 17% both sides and 3% said they didn't know.

A 1917 Punch cartoon depicts King George sweeping away his German titles.