The War of the Worlds (1938 radio drama)

Popular legend holds that some of the radio audience may have been listening to The Chase and Sanborn Hour with Edgar Bergen on NBC and tuned in to "The War of the Worlds" during a musical interlude, thereby missing the clear introduction indicating that the show was a work of science fiction.

The first portion of the episode climaxes with a live report from a rooftop in Manhattan, from where a correspondent describes citizens fleeing from poison smoke released by towering Martian "war machines" until he coughs and falls silent.

The second portion of the show shifts to a more conventional radio drama format that follows a survivor (played by Welles) dealing with the aftermath of the invasion and the ongoing Martian occupation of Earth.

Welles, immersed in rehearsing the Mercury stage production of Danton's Death scheduled to open the following week, played the record at an editorial meeting that night in his suite at the St. Regis Hotel.

After hearing "Air Raid" on the Columbia Workshop earlier that same evening, Welles thought the "War of the Worlds" script was dull, and he advised the writers to add more news flashes and eyewitness accounts to create a stronger sense of urgency and excitement.

[4]: 398 Stewart worked with Herrmann and the orchestra to sound like a dance band,[17] and became the person Welles later credited as being largely responsible for the quality of "The War of the Worlds" broadcast.

"During that time, men travelled long distances, large bodies of troops were mobilized, cabinet meetings were held, savage battles fought on land and in the air.

With infinite complacence, people went to and fro over the earth about their little affairs, serene in the assurance of their dominion over this small spinning fragment of solar driftwood which by chance or design man has inherited out of the dark mystery of Time and Space.

Police officers approach the Martian waving a flag of truce, but it and its companions respond by firing a heat ray, which incinerates the delegation and ignites the nearby woods and cars as the crowd screams.

Phillips's shouts about incoming flames are cut off mid-sentence, and after a moment of dead air, an announcer explains that the remote broadcast was interrupted due to "some difficulty with [their] field transmission".

He reads a final bulletin stating that Martian cylinders have fallen all over the country, then describes the smoke approaching his location until he coughs and apparently collapses, leaving only the sounds of the panicked city in the background.

In Newark, he encounters an opportunistic militiaman who holds fascistic ideals and declares his intent to use Martian weaponry to take control of both the invaders and their human slaves; saying that he wants no part of "his world", Pierson leaves the stranger with his delusions.

After the conclusion of the play, Welles reassumed his role as host and told listeners that the broadcast was intended to be merely a "holiday offering", the equivalent of the Mercury Theater "dressing up in a sheet, jumping out of a bush and saying, 'Boo!'"

At 8:32, Houseman noticed Taylor step out of the studio to take a telephone call in the control room, who returned four minutes later looking "pale as death", as he had been ordered to immediately interrupt "The War of the Worlds" broadcast with an announcement of the program's fictional content.

By the time the order was given, the fictional news reporter played by Ray Collins was choking on poison gas as the Martians overwhelmed New York and the program was less than a minute away from its first scheduled break, which proceeded as previously planned.

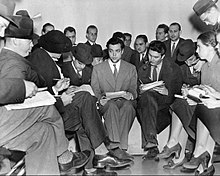

[4]: 404 Paul White, head of CBS News, was quickly summoned to the office, "and there bedlam reigned", he wrote: The telephone switchboard, a vast sea of light, could handle only a fraction of incoming calls.

They immediately left the theatre, and standing on the corner of Broadway and 42nd Street, they read the lighted bulletin that circled the New York Times building: ORSON WELLES CAUSES PANIC.

Many newspapers assumed that the large number of phone calls and the scattered reports of listeners rushing about or fleeing their homes proved the existence of a mass panic, but such behavior was never widespread.

[45] "[T]he panic and mass hysteria so readily associated with 'The War of the Worlds' did not occur on anything approaching a nationwide dimension", American University media historian W. Joseph Campbell wrote in 2003.

[1] Of the nearly 2,000 letters mailed to Welles and the Federal Communications Commission after "The War of the Worlds", currently held by the University of Michigan and the National Archives and Records Administration, roughly 27% came from frightened listeners or people who witnessed any panic.

The total number of protest letters sent to Welles and the FCC was also low in comparison with other controversial radio broadcasts of the period, suggesting that the audience was small and the fright severely limited.

Further shrinking the potential audience, some CBS network affiliates, including some in large markets such as Boston's WEEI, had pre-empted The Mercury Theatre on the Air, in favor of local commercial programming.

"The supposed panic was so tiny as to be practically immeasurable on the night of the broadcast", media historians Jefferson Pooley and Michael J. Socolow wrote in Slate on its 75th anniversary in 2013; "Almost nobody was fooled".

[31] The Twin City Sentinel of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, pointed out that the situation could have been even worse if most people had not been listening to Bergen's show: "Charlie McCarthy last night saved the United States from a sudden and panicky death by hysteria.

Noting that any intelligent listener would have realized the broadcast was fictional, the Chicago Tribune opined, "it would be more tactful to say that some members of the radio audience are a trifle retarded mentally, and that many a program is prepared for their consumption."

Justin Levine, a producer at KFI in Los Angeles, wrote that "the anecdotal nature of such reporting makes it difficult to objectively assess the true extent and intensity of the panic".

[57]: 175–176 A condensed version of the script for "The War of the Worlds" appeared in the debut issue of Radio Digest magazine (February 1939), in an article on the broadcast that credited "Orson Welles and his Mercury Theatre players".

The live presentation of Nelson S. Bond's documentary play recreated the 1938 performance of "The War of the Worlds" in the CBS studio, using the script as a framework for a series of factual narratives about a cross-section of radio listeners.

[67] Initially apologetic about the supposed panic his broadcast had caused, and privately fuming that newspaper reports of lawsuits were either greatly exaggerated or totally fabricated,[52] Welles later embraced the story as part of his personal myth: "Houses were emptying, churches were filling up; from Nashville to Minneapolis there was wailing in the streets and the rending of garments," he told Bogdanovich.

[96] Most of the cast for this production had appeared in one or more incarnations of Star Trek, including Leonard Nimoy, John de Lancie, Dwight Schultz, Wil Wheaton, Gates McFadden, Brent Spiner, Armin Shimerman, Jerry Hardin, and Tom Virtue.