The World of Yesterday

"When I attempt to find a simple formula for the period in which I grew up, before the First World War, I hope that I convey its fullness by calling it the Golden Age of Security.

Young girls were guarded and occupied so that they could never think about sexuality.Zweig notes that the situation had dramatically improved for both women and men, and the generation after him was much more fortunate.

Zweig went to college for the sole purpose of earning a doctorate in any field — to satisfy his family's aspirations — not to learn; To paraphrase Ralph Waldo Emerson, "good books replace the best universities."

Later, he offered one of his works to the "Neue Freie Presse" — the cultural pages of reference in Austria-Hungary at that time — and had the honor of being published at only 19 years old.

He decides to continue his studies in Berlin to change the atmosphere, escape his young celebrity, and meet people beyond the circle of the Jewish bourgeoisie in Vienna.

After speaking at length with him, he decides to make his work known by translating it, a task he observes as a duty and an opportunity to refine his literary talents.

Zweig recounts several anecdotes about him, taking it upon himself to paint a portrait of a young man — or somewhat of a genius — compassionate, reserved, refined, and striving to remain discreet and temperate.

Having pity and a certain sympathy for the thief, Zweig decides not to file a complaint, thus earning for himself the whole neighborhood's antipathy, leading to his leaving rather quickly.

He also takes away, on the advice of his friend Archibald GB Russell, a portrait of "King John" by William Blake, which he never tired of admiring.

Zweig nurtures an almost religious devotion to the writings that preceded great artists' masterpieces, notably Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

The title of the chapter then takes on its meaning: it was by chance that he did not enter the golden books of literature for his talents as writers in versified dramas — things he would have liked — but for his novels.

He ended his trip to America by contemplating the Panama Canal's technical prowess: a titanic project, costly — especially in human lives — started by the Europeans and completed by the Americans.

The next day, he ran into Bertha von Suttner, who foretold the turn of events: When he went to the cinema in the small town of Tours, he was amazed to see that the hatred — displayed against Kaiser Wilhelm II — had already spread throughout France.

Zweig, rejected by his friends who consider him almost a traitor to his nation, for his part, undertakes a personal war against this murderous passion.

Zweig makes it his mission, rather than only not taking part in this hatred, to actively fight against this propaganda, less to convince than to spread his message simply.

He decides to fight this propaganda by writing a drama, emphasizing Biblical themes, particularly Jewish wanderings and trials, praising the losers' destiny.

He met two Austrians in Salzburg on his journey to Switzerland who would play a significant role once Austria had surrendered: Heinrich Lammasch and Ignaz Seipel.

Paradoxically, theaters, concerts, and operas are active, and artistic and cultural life is in full swing: Zweig explains this by the general feeling that this could be the last performance.

Full of apprehension about the reception we reserve for an Austrian, he is surprised by the Italians' hospitality and thoughtfulness, telling himself that the masses had not changed profoundly because of the propaganda.

Zweig says he has carried out important synthesis work — notably with Marie-Antoinette — and sees his capacity for conciseness as a defining element of his success.

However, despite his success, Zweig says he remains humble and does not change his habits: he continues to stroll with his friends in the streets, and he does not disdain going to the provinces to stay in small hotels.

Nevertheless, Zweig was struck that the Berghof, Hitler's mountain residence in Berchtesgaden, an area of early Nazi activity, was just across the valley from his own house outside Salzburg.

He then describes the progressive censorship that descended on his opera Die schweigsame Frau, even as he witnessed the artistic power of his co-worker, the composer Richard Strauss.

Due to Zweig's politically neutral writings and Strauss' unrivaled fame in Germany, it was impossible to censor the opera.

Delighted to speak with Freud one last time, an admirable scholar devoted to the cause of truth, Zweig attended his funeral shortly after.

At a PEN-Club conference, he stopped in Vigo, Spain, then in the hands of General Franco, noting again with bitterness the young people swaggering in fascist uniforms.

His friends had firmly believed that the neighboring countries would never accept such an event, but Zweig had already, in autumn 1937, said goodbye to his mother and the rest of his family.

Of particular interest are Zweig's description of various intellectual personalities, including Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern political Zionism, Rainer Maria Rilke, the Belgian poet Emile Verhaeren, the composer Ferruccio Busoni, the philosopher and antifascist Benedetto Croce, Maxim Gorky, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Arthur Schnitzler, Franz Werfel, Gerhart Hauptmann, James Joyce, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Bertha von Suttner, the German industrialist and politician Walther Rathenau and the pacifist and friend Romain Rolland.

Zweig particularly admired the poetry of Hugo von Hofmannsthal and expressed this admiration and Hofmannsthal's influence on his generation in the chapter devoted to his school years: "The appearance of the young Hofmannsthal is and remains notable as one of the greatest miracles of accomplishment early in life; in world literature, except for Keats and Rimbaud, I know no other youthful example of a similar impeccability in the mastering of language, no such breadth of spiritual buoyancy, nothing more permeated with a poetic substance even in the most simple lines, than in this magnificent genius, who already in his sixteenth and seventeenth year had inscribed himself in the eternal annals of the German language with unextinguishable verses and prose which today has still not been surpassed.

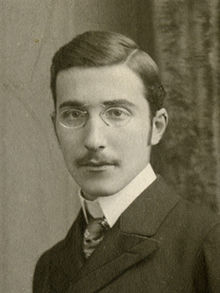

Stefan Zweig, l'autore del più famoso libro sull'Impero asburgico, Die Welt von Gestern