The Exodus

[10] The pharaoh becomes concerned by the number and strength of the Israelites in Egypt and enslaves them, commanding them to build at two "supply" or "store cities" called Pithom and Rameses (Exodus 1:11).

Grown to a young man, Moses kills an Egyptian he sees beating a Hebrew slave, and takes refuge in to the land of Midian, where he marries Tzipporah, a daughter of the Midianite priest Jethro.

[15] Meanwhile, Moses goes to Mount Horeb, where Yahweh appears in a burning bush and commands him to go to Egypt to free the Hebrew slaves and bring them to the Promised Land in Canaan.

Moses and Aaron then go to Pharaoh and ask him to let the Israelites go into the desert for a religious festival, but he refuses and increases their workload, commanding them to make bricks without straw.

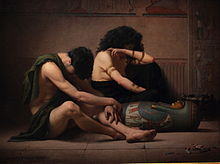

After this, Yahweh inflicts a series of Plagues on the Egyptians each time Moses repeats his demand and Pharaoh refuses to release the Israelites.

The Israelites will have to remain in the wilderness for forty years,[20] and Yahweh kills the spies through a plague except for the righteous Joshua and Caleb, who will be allowed to enter the promised land (Numbers 13:36-38).

A group of Israelites led by Korah, son of Izhar, rebels against Moses, but Yahweh opens the earth and sends them living to Sheol (Numbers 16:1-33).

[27] The biblical Exodus narrative is best understood as a founding myth of the Jewish people, providing an ideological foundation for their culture and institutions, not an accurate depiction of the history of the Israelites.

[36] The earliest surviving historical mention of the Israelites, the Egyptian Merneptah Stele (c. 1207 BCE), appears to place them in or around Canaan and gives no indication of any exodus.

[37] Archaeologist Israel Finkelstein argues from his analysis of the itinerary lists in the books of Exodus, Numbers and Deuteronomy that the biblical account represents a long-term cultural memory, spanning the 16th to 10th centuries BCE, rather than a specific event: "The beginning is vague and now untraceable.

[47][49][50] Many other scholars reject this view, and instead see the biblical exodus traditions as the invention of the exilic and post-exilic Jewish community, with little to no historical basis.

[52] Philip R. Davies suggests that the story may have been inspired by the return to Israel of Israelites and Judaeans who were placed in Egypt as garrison troops by the Assyrians in the fifth and sixth centuries BCE, during the exile.

[60] Evidence from the Bible suggests that the Exodus from Egypt formed a "foundational mythology" or "state ideology" for the Northern Kingdom of Israel.

[64] Russell and Frank Moore Cross argue that the Israelites of the Northern Kingdom may have believed that the calves at Bethel and Dan were made by Aaron.

[67] The psalm's version of the Exodus contains some important differences from what is found in the Pentateuch: there is no mention of Moses, and the manna is described as "food of the mighty" rather than as bread in the wilderness.

[68] Nadav Na'aman argues for other signs that the Exodus was a tradition in Judah before the destruction of the northern kingdom, including the Song of the Sea and Psalm 114, as well as the great political importance that the narrative came to assume there.

Meindert Dijkstra writes that while the historicity of the Mosaic origin of the Nehushtan is unlikely, its association with Moses appears genuine rather than the work of a later redactor.

[73] Mark Walter Bartusch notes that the nehushtan is not mentioned at any prior point in Kings, and suggests that the brazen serpent was brought to Jerusalem from the Northern Kingdom after its destruction in 722 BCE.

[74] Joel S. Baden notes that "[t]he seams [between the Exodus and Wilderness traditions] still show: in the narrative of Israel's rescue from Egypt there is little hint that they will be brought anywhere other than Canaan – yet they find themselves heading first, unexpectedly, and in no obvious geographical order, to an obscure mountain.

[85] Manetho, also preserved in Josephus's Against Apion, tells how 80,000 lepers and other "impure people", led by a priest named Osarseph, join forces with the former Hyksos, now living in Jerusalem, to take over Egypt.

They wreak havoc until the Pharaoh and his son chase them out to the borders of Syria, where Osarseph gives the lepers a law code and changes his name to Moses.

[93] Egyptologist Jan Assmann proposed that the story comes from oral sources that "must [...] predate the first possible acquaintance of an Egyptian writer with the Hebrew Bible.

"[88] Assmann suggested that the story has no single origin but rather combines numerous historical experiences, notably the Amarna and Hyksos periods, into a folk memory.

[85] Erich S. Gruen suggested that it may have been the Jews themselves that inserted themselves into Manetho's narrative, in which various negative actions from the point of view of the Egyptians, such as desecrating temples, are interpreted positively.

In the Bible, the Exodus is frequently mentioned as the event that created the Israelite people and forged their bond with God, being described as such by the prophets Hosea, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel.

[97] The fringes worn at the corners of traditional Jewish prayer shawls are described as a physical reminder of the obligation to observe the laws given at the climax of Exodus: "Look at it and recall all the commandments of the Lord" (Numbers).

[107] It is celebrated by building a sukkah, a temporary shelter also called a booth or tabernacle, in which the rituals of Sukkot are performed, recalling the impermanence of the Israelites' homes during the desert wanderings.

[112] In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus reverses the direction of the Exodus by escaping from the Massacre of the Innocents committed by Herod the Great before himself returning from Egypt (Matt 2:13-15).

American "founding fathers" Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin recommended for the Great Seal of the United States to depict Moses leading the Israelites across the Red Sea.

African Americans suffering under slavery and racial oppression interpreted their situation in terms of the Exodus, making it a catalyst for social change.