Theories of urban planning

In keeping with the rising power of industry, the source of the planning authority in the Sanitary movement included both traditional governmental offices and private development corporations.

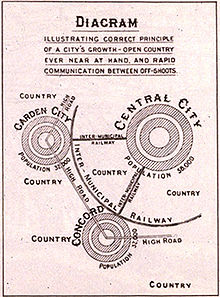

[14] His influences included Benjamin Walter Richardson, who had published a pamphlet in 1876 calling for low population density, good housing, wide roads, an underground railway and for open space; Thomas Spence who had supported common ownership of land and the sharing of the rents it would produce; Edward Gibbon Wakefield who had pioneered the idea of colonizing planned communities to house the poor in Adelaide (including starting new cities separated by green belts at a certain point); James Silk Buckingham who had designed a model town with a central place, radial avenues and industry in the periphery; as well as Alfred Marshall, Peter Kropotkin and the back-to-the-land movement, which had all called for the moving of masses to the countryside.

[16] To make this happen, a group of individuals would establish a limited-dividend company to buy cheap agricultural land, which would then be developed with investment from manufacturers and housing for the workers.

[22] His main influences were the geographers Élisée Reclus and Paul Vidal de La Blache, as well as the sociologist Pierre Guillaume Frédéric le Play.

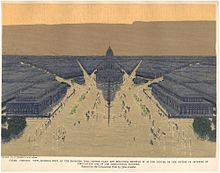

[27] The Regional Planning Association of America advanced his ideas, coming up with the 'regional city' which would have a variety of urban communities across a green landscape of farms, parks and wilderness with the help of telecommunication and the automobile.

In the United States, Frank Lloyd Wright similarly identified vehicular mobility as a principal planning metric.

[46] In his Usonian vision, he described the city as"spacious, well-landscaped highways, grade crossings eliminated by a new kind of integrated by-passing or over- or under-passing all traffic in cultivated or living areas … Giant roads, themselves great architecture, pass public service stations .

passing by farm units, roadside markets, garden schools, dwelling places, each on its acres of individually adorned and cultivated ground".

[53] In contrast, she defended the dense traditional inner-city neighborhoods like Brooklyn Heights or North Beach, San Francisco, and argued that an urban neighbourhood required about 200-300 people per acre, as well as a high net ground coverage at the expense of open space.

[54] She also advocated for a diversity of land uses and building types, with the aim of having a constant churn of people throughout the neighbourhood across the times of the day.

[54] As she believed that such environments were essentially self-organizing, her approach was effectively one of laissez-faire, and has been criticized for not being able to guarantee "the development of good neighbourhoods".

[62] Similar ideas had been put forward by Geddes, who had seen cities and their regions as analogous to organisms, though they did not receive much attention while planning was dominated by architects.

[62] There were also doubts raised about the goal of producing detailed blueprints of how cities should look like in the end, instead suggesting the need for more flexible plans with trajectories instead of fixed futures.

[66] Beginning in the late 1950s and early 1960s, critiques of the rational paradigm began to emerge and formed into several different schools of planning thought.

He posited that organizations could accomplish this by essentially scanning the environment on multiple levels and then choose different strategies and tactics to address what they found there.

[70] Jane Jacobs's 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities,[71] was a sustained critique of urban planning as it had developed within modernism,[72] and played a major role in turning public opinion against modernist planners, notably Robert Moses.

[77][78] It proposed a central business core, circled by transitional immigrant and working class areas, then by more affluent outer commuter rings.

The LA School analysis emphasized the global-local connection, pervasive social fragmentation, and a "reterritorialization of the urban process in which hinterland organizes the center (in direct contradiction to the Chicago model)".

[80] A review of postmodern urbanism literature, published in 2018 in the Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, examined coverage of style, epoch, and method, noting a general lack of cohesive definition, and the use of questionable interpretation to form conceptual statements.

[91] As a result, he came to the conclusion that:"When dwellers control the major decisions and are free to make their own contributions in the design, construction or management of their housing, both this process and the environment produced stimulate individual and social well-being.

When people have no control over nor responsibility for key decisions in the housing process, on the other hand, dwelling environments may instead become a barrier to personal fulfillment and a burden on the economy.

[92] Self-build was later again taken up by Christopher Alexander, who led a project called People Rebuild Berkeley in 1972, with the aim to create "self-sustaining, self-governing" communities, though it ended up being closer to traditional planning.

It concerns itself with ensuring that all people are equally represented in the planning process by advocating for the interests of the underprivileged and seeking social change.

Grabow and Heskin provided a critique of planning as elitist, centralizing and change-resistant, and proposed a new paradigm based upon systems change, decentralization, communal society, facilitation of human development and consideration of ecology.

The bargaining model views planning as the result of giving and take on the part of a number of interests who are all involved in the process.

The model seeks to include a broad range of voice to enhance the debate and negotiation that is supposed to form the core of actual plan making.

The Melbourne Docklands, for example, was largely an initiative pushed by private developers to redevelop the waterfront into a high-end residential and commercial district.

Recent theories of urban planning, espoused, for example by Salingaros see the city as an adaptive system that grows according to process similar to those of plants.

[103] Such theories also advocate participation by inhabitants in the design of the urban environment, as opposed to simply leaving all development to large-scale construction firms.

The contents of the carrier structure may include street pattern, landscape architecture, open space, waterways, and other infrastructure.