General relativity

Newton's law of universal gravitation, which describes classical gravity, can be seen as a prediction of general relativity for the almost flat spacetime geometry around stationary mass distributions.

The time-dependent solutions of general relativity enable us to talk about the history of the universe and have provided the modern framework for cosmology, thus leading to the discovery of the Big Bang and cosmic microwave background radiation.

In 1907, beginning with a simple thought experiment involving an observer in free fall (FFO), he embarked on what would be an eight-year search for a relativistic theory of gravity.

Lemaître used these solutions to formulate the earliest version of the Big Bang models, in which the universe has evolved from an extremely hot and dense earlier state.

[2][19][20] Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar has noted that at multiple levels, general relativity exhibits what Francis Bacon has termed a "strangeness in the proportion" (i.e. elements that excite wonderment and surprise).

The work presumes a standard of education corresponding to that of a university matriculation examination, and, despite the shortness of the book, a fair amount of patience and force of will on the part of the reader.

Bringing gravity into play, and assuming the universality of free fall motion, an analogous reasoning as in the previous section applies: there are no global inertial frames.

In special relativity, mass turns out to be part of a more general quantity called the energy–momentum tensor, which includes both energy and momentum densities as well as stress: pressure and shear.

[41] Matching the theory's prediction to observational results for planetary orbits or, equivalently, assuring that the weak-gravity, low-speed limit is Newtonian mechanics, the proportionality constant

[42] When there is no matter present, so that the energy–momentum tensor vanishes, the results are the vacuum Einstein equations, In general relativity, the world line of a particle free from all external, non-gravitational force is a particular type of geodesic in curved spacetime.

The Christoffel symbols are functions of the four spacetime coordinates, and so are independent of the velocity or acceleration or other characteristics of a test particle whose motion is described by the geodesic equation.

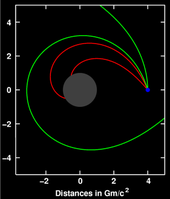

In general relativity, the effective gravitational potential energy of an object of mass m revolving around a massive central body M is given by[43][44] A conservative total force can then be obtained as its negative gradient where L is the angular momentum.

[45] The derivation outlined in the previous section contains all the information needed to define general relativity, describe its key properties, and address a question of crucial importance in physics, namely how the theory can be used for model-building.

In the field of numerical relativity, powerful computers are employed to simulate the geometry of spacetime and to solve Einstein's equations for interesting situations such as two colliding black holes.

[73] As one examines suitable model spacetimes (either the exterior Schwarzschild solution or, for more than a single mass, the post-Newtonian expansion),[74] several effects of gravity on light propagation emerge.

[77] In the parameterized post-Newtonian formalism (PPN), measurements of both the deflection of light and the gravitational time delay determine a parameter called γ, which encodes the influence of gravity on the geometry of space.

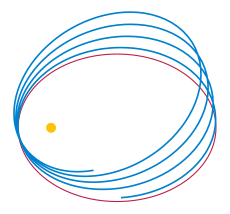

For him, the fact that his theory gave a straightforward explanation of Mercury's anomalous perihelion shift, discovered earlier by Urbain Le Verrier in 1859, was important evidence that he had at last identified the correct form of the gravitational field equations.

It is used to detect the presence and distribution of dark matter, provide a "natural telescope" for observing distant galaxies, and to obtain an independent estimate of the Hubble constant.

[120] They are expected to yield information about black holes and other dense objects such as neutron stars and white dwarfs, about certain kinds of supernova implosions, and about processes in the very early universe, including the signature of certain types of hypothetical cosmic string.

[81][82][83] Whenever the ratio of an object's mass to its radius becomes sufficiently large, general relativity predicts the formation of a black hole, a region of space from which nothing, not even light, can escape.

[127] General relativity plays a central role in modelling all these phenomena,[128] and observations provide strong evidence for the existence of black holes with the properties predicted by the theory.

[136] Predictions, all successful, include the initial abundance of chemical elements formed in a period of primordial nucleosynthesis,[137] the large-scale structure of the universe,[138] and the existence and properties of a "thermal echo" from the early cosmos, the cosmic background radiation.

[147] An even larger question is the physics of the earliest universe, prior to the inflationary phase and close to where the classical models predict the big bang singularity.

Kurt Gödel showed[149] that solutions to Einstein's equations exist that contain closed timelike curves (CTCs), which allow for loops in time.

In 1962 Hermann Bondi, M. G. van der Burg, A. W. Metzner[151] and Rainer K. Sachs[152] addressed this asymptotic symmetry problem in order to investigate the flow of energy at infinity due to propagating gravitational waves.

Rather, relations that hold true for all geodesics, such as the Raychaudhuri equation, and additional non-specific assumptions about the nature of matter (usually in the form of energy conditions) are used to derive general results.

The best-known examples are black holes: if mass is compressed into a sufficiently compact region of space (as specified in the hoop conjecture, the relevant length scale is the Schwarzschild radius[156]), no light from inside can escape to the outside.

But some solutions of Einstein's equations have "ragged edges"—regions known as spacetime singularities, where the paths of light and falling particles come to an abrupt end, and geometry becomes ill-defined.

[191][192] Attempts to generalize ordinary quantum field theories, used in elementary particle physics to describe fundamental interactions, so as to include gravity have led to serious problems.

[196] The theory promises to be a unified description of all particles and interactions, including gravity;[197] the price to pay is unusual features such as six extra dimensions of space in addition to the usual three.