Gravitational lens

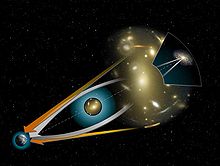

A gravitational lens is matter, such as a cluster of galaxies or a point particle, that bends light from a distant source as it travels toward an observer.

[3][4][5][6] Orest Khvolson (1924)[7] and Frantisek Link (1936)[8] are generally credited with being the first to discuss the effect in print, but it is more commonly associated with Einstein, who made unpublished calculations on it in 1912[9] and published an article on the subject in 1936.

[10] In 1937, Fritz Zwicky posited that galaxy clusters could act as gravitational lenses, a claim confirmed in 1979 by observation of the Twin QSO SBS 0957+561.

More commonly, where the lensing mass is complex (such as a galaxy group or cluster) and does not cause a spherical distortion of spacetime, the source will resemble partial arcs scattered around the lens.

Henry Cavendish in 1784 (in an unpublished manuscript) and Johann Georg von Soldner in 1801 (published in 1804) had pointed out that Newtonian gravity predicts that starlight will bend around a massive object[15] as had already been supposed by Isaac Newton in 1704 in his Queries No.1 in his book Opticks.

[17] The first observation of light deflection was performed by noting the change in position of stars as they passed near the Sun on the celestial sphere.

The observations were performed in 1919 by Arthur Eddington, Frank Watson Dyson, and their collaborators during the total solar eclipse on May 29.

Observations were made simultaneously in the cities of Sobral, Ceará, Brazil and in São Tomé and Príncipe on the west coast of Africa.

When asked by his assistant what his reaction would have been if general relativity had not been confirmed by Eddington and Dyson in 1919, Einstein said "Then I would feel sorry for the dear Lord.

[10] Although Einstein made unpublished calculations on the subject,[9] the first discussion of the gravitational lens in print was by Khvolson, in a short article discussing the "halo effect" of gravitation when the source, lens, and observer are in near-perfect alignment,[7] now referred to as the Einstein ring.

In 1936, after some urging by Rudi W. Mandl, Einstein reluctantly published the short article "Lens-Like Action of a Star By the Deviation of Light In the Gravitational Field" in the journal Science.

[10] In 1937, Fritz Zwicky first considered the case where the newly discovered galaxies (which were called 'nebulae' at the time) could act as both source and lens, and that, because of the mass and sizes involved, the effect was much more likely to be observed.

G. Klimov, S. Liebes, and Sjur Refsdal recognized independently that quasars are an ideal light source for the gravitational lens effect.

This gravitational lens was discovered by Dennis Walsh, Bob Carswell, and Ray Weymann using the Kitt Peak National Observatory 2.1 meter telescope.

[24] In the 1980s, astronomers realized that the combination of CCD imagers and computers would allow the brightness of millions of stars to be measured each night.

In a dense field, such as the galactic center or the Magellanic clouds, many microlensing events per year could potentially be found.

This led to efforts such as Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment, or OGLE, that have characterized hundreds of such events, including those of OGLE-2016-BLG-1190Lb and OGLE-2016-BLG-1195Lb.

The angle of deflection is toward the mass M at a distance r from the affected radiation, where G is the universal constant of gravitation, and c is the speed of light in vacuum.

If such a search is done using well-calibrated and well-parameterized instruments and data, a result similar to the northern survey can be expected.

Due to the high frequency used, the chances of finding gravitational lenses increases as the relative number of compact core objects (e.g. quasars) are higher (Sadler et al. 2006).

A statistical analysis of specific cases of observed microlensing over the time period of 2002 to 2007 found that most stars in the Milky Way galaxy hosted at least one orbiting planet within 0.5 to 10 AU.

[28] In 2009, weak gravitational lensing was used to extend the mass-X-ray-luminosity relation to older and smaller structures than was previously possible to improve measurements of distant galaxies.

[29] As of 2013[update] the most distant gravitational lens galaxy, J1000+0221, had been found using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope.

[32] Research published Sep 30, 2013 in the online edition of Physical Review Letters, led by McGill University in Montreal, Québec, Canada, has discovered the B-modes, that are formed due to gravitational lensing effect, using National Science Foundation's South Pole Telescope and with help from the Herschel space observatory.

The high gain for potentially detecting signals through this lens, such as microwaves at the 21-cm hydrogen line, led to the suggestion by Frank Drake in the early days of SETI that a probe could be sent to this distance.

[40] A critique of the concept was given by Landis,[41] who discussed issues including interference of the solar corona, the high magnification of the target, which will make the design of the mission focal plane difficult, and an analysis of the inherent spherical aberration of the lens.

In 2020, NASA physicist Slava Turyshev presented his idea of Direct Multipixel Imaging and Spectroscopy of an Exoplanet with a Solar Gravitational Lens Mission.

[42] Kaiser, Squires and Broadhurst (1995),[44] Luppino & Kaiser (1997)[45] and Hoekstra et al. (1998) prescribed a method to invert the effects of the point spread function (PSF) smearing and shearing, recovering a shear estimator uncontaminated by the systematic distortion of the PSF.

As a result, the shear effects in weak lensing need to be determined by statistically preferred orientations.

KSB calculate how a weighted ellipticity measure is related to the shear and use the same formalism to remove the effects of the PSF.