Theramenes

He had commanded the group of Greek colonists who founded Amphipolis in 437–6 BC,[6] had served as a general on several occasions before and during the Peloponnesian War,[7] and was one of the signers of the Peace of Nicias.

In the wake of the Athenian defeat in Sicily, revolts began to break out among Athens' subject states in the Aegean Sea and the Peace of Nicias fell apart; the Peloponnesian War resumed in full by 412 BC.

In this context, a number of Athenian aristocrats, led by Peisander and with Theramenes prominent among their ranks, began to conspire to overthrow the city's democratic government.

"[15] Calling the assembly together, the conspirators proposed a series of measures by which the democracy was formally replaced with a government of 400 chosen men, who were to select and convene a larger body of 5,000 as time went on.

The extremist faction, led by Phrynichus, containing such prominent leaders of the coup as Peisander and Antiphon, and dominant within the 400, opposed broadening the base of the oligarchy, and were willing to seek peace with Sparta on almost any terms.

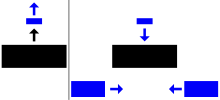

With internal dissent increasing, they joined these new fortifications to existing walls to form a redoubt defensible against attacks from land or sea, which contained a large warehouse into which the extremists moved most of the city's grain supply.

[22] Theramenes protested strongly against the building of this fortification, arguing that its purpose was not to keep the democrats out, but to be handed over to the Spartans; Thucydides testifies that his charges were not without substance, as the extremists were actually contemplating such an action.

With the extremists unable to take effective action in this case, and with the Peloponnesian fleet overrunning Aegina (a logical stopping point on the approach to Piraeus), Theramenes and his party decided to act.

[25] Donald Kagan has suggested that this call was probably instigated by Theramenes' party, who wanted the 5,000 to govern; the hoplites tearing down the fortification might well have preferred a return to the democracy.

[33] In the wake of this victory, the Athenians captured Cyzicus and constructed a fort at Chrysopolis, from which they extracted a customs duty of one tenth on all ships passing through the Bosporus.

[citation needed] In the next year, however, he did sail as a trierarch in the scratch Athenian relief fleet sent out to relieve Conon, who had been blockaded with 40 triremes at Mytilene by Callicratidas.

"For," he states, "although they could have had the help of Theramenes and his associates in the trial, men who both were able orators and had many friends and, most important of all, had been participants in the events relative to the battle, they had them, on the contrary, as adversaries and bitter accusers.

At first, it appeared that they might be treated leniently, but in the end, public displays of bereavement by the families of the deceased and aggressive prosecution by a politician named Callixenus swung the opinion of the assembly; the six generals were tried as a group and executed.

[46] The Athenian public, as the grief and anger prompted by the disaster cooled, came to regret their action, and for thousands of years historians and commentators have pointed to the incident as perhaps the greatest miscarriage of justice the city's government ever perpetrated.

[48] The Athenians were initially intransigent, going so far as to imprison a man who suggested that a stretch of the long walls be torn down as the Spartans had insisted,[49] but the reality of their situation soon compelled them to consider compromises.

[53] Theramenes returned to Athens and presented the results of the negotiations to the assembly; although some still favored holding out, the majority voted to accept the terms; the Peloponnesian War, after 28 years, was at an end.

[63] This, in turn, marked the beginning of even greater excesses; to pay the Spartan garrison's wages, Critias and the leaders ordered each of the Thirty to arrest and execute a metic, or resident alien, and confiscate his property.

[65] Famously, he branded him with the nickname "cothurnus", the name of a boot worn on the stage that could fit either foot; Theramenes, he proclaimed, was ready to serve either the democratic or oligarchic cause, seeking only to further his own personal interest.

[67] Accordingly, after conferring with the Thirty, Critias ordered men with daggers to line the stage in front of the audience and then struck Theramenes' name from the roster of the 3,000, denying him his right to a trial.

[68] Theramenes, springing to a nearby altar for sanctuary, admonished the assemblage not to permit his murder, but to no avail; the Eleven, keepers of the prison, entered, dragged him away, and forced him to drink a cup of hemlock.

Theramenes, imitating a popular drinking game in which the drinker toasted a loved one as he finished his cup, downed the poison and then flung the dregs to the floor, exclaiming "Here's to the health of my beloved Critias!

[71] Xenophon adopts a similarly hostile attitude in the early parts of his work, but apparently had a change of heart during the chronological break in composition that divides the second book of the Hellenica; his portrayal of Theramenes during the reign of the Thirty Tyrants is altogether more favorable than that of his earlier years.

[75][76] The discovery of Aristotle's Constitution of the Athenians in 1890 reversed this trend for the broad assessment of Theramenes' character,[77] and Diodorus' account of the Arginusae trial has been preferred by scholars since Antony Andrewes undermined Xenophon's account in the 1970s; Diodorus' more melodramatic passages, such as his elaborate presentation of Theramenes' last moments, are still discounted,[78] but he is now preferred on a number of issues, and on the Arginusae trial in particular.

Donald Kagan has said of him that "...his entire career reveals him to be a patriot and a true moderate, sincerely committed to a constitution granting power to the hoplite class, whether in the form of a limited democracy or a broadly based oligarchy",[81] while John Fine has noted that "like many a person following a middle course, he was hated by both political extremes.

"[82] In the millennia since his death, Theramenes has been both idealized and reviled; his brief seven-year career in the spotlight, touching as it did on all the major points of controversy in the last years of the Peloponnesian War, has been subject to myriad different interpretations.