Theravada

[1][2] The school's adherents, termed Theravādins (anglicized from Pali theravādī),[3][4] have preserved their version of Gautama Buddha's teaching or Dhamma in the Pāli Canon for over two millennia.

[10][11][12] From both India, as its historical origin, and Sri Lanka, as its principal center of development, the Theravāda tradition subsequently spread to Southeast Asia, where it became the dominant form of Buddhism.

[14][15] Theravāda sources trace their tradition to the Third Buddhist council when elder Moggaliputta-Tissa is said to have compiled the Kathavatthu, an important work which lays out the Vibhajjavāda doctrinal position.

[26][27] Epigraphical evidence has established that Theravāda Buddhism became a dominant religion in the Southeast Asian kingdoms of Sri Ksetra and Dvaravati from about the 5th century CE onwards.

[45] In Burma, an influential modernist figure was king Mindon Min (1808–1878), known for his patronage of the Fifth Buddhist council (1871) and the Tripiṭaka tablets at Kuthodaw Pagoda (still the world's largest book) with the intention of preserving the Buddha Dhamma.

Meanwhile, in Thailand (the only Theravāda nation to retain its independence throughout the colonial era), the religion became much more centralized, bureaucratized and controlled by the state after a series of reforms promoted by Thai kings of the Chakri dynasty.

[53] While the Khmer Rouge effectively destroyed Cambodia's Buddhist institutions, after the end of the communist regime the Cambodian Sangha was re-established by monks who had returned from exile.

On this basis, these Early Buddhist texts (i.e. the Nikayas and parts of the Vinaya) are generally believed to be some of the oldest and most authoritative sources on the doctrines of pre-sectarian Buddhism by modern scholars.

[82] Because the Abhidhamma focuses on analyzing the internal lived experience of beings and the intentional structure of consciousness, it has often been compared to a kind of phenomenological psychology by numerous modern scholars such as Nyanaponika, Bhikkhu Bodhi and Alexander Piatigorsky.

[85] However some scholars, such as Frauwallner, also hold that the early Abhidhamma texts developed out of exegetical and catechetical work which made use of doctrinal lists which can be seen in the suttas, called matikas.

They include central concepts such as:[96] The orthodox standpoints of Theravāda in comparison to other Buddhist schools are presented in the Kathāvatthu ("Points of Controversy"), as well as in other works by later commentators like Buddhaghosa.

In the Pāli Nikayas, the Buddha teaches through an analytical method in which experience is explained using various conceptual groupings of physical and mental processes, which are called "dhammas".

Expanding this model, Theravāda Abhidhamma scholasticism concerned itself with analyzing "ultimate truth" (paramattha-sacca) which it sees as being composed of all possible dhammas and their relationships.

[131] Noa Ronkin defines dhammas as "the constituents of sentient experience; the irreducible 'building blocks' that make up one's world, albeit they are not static mental contents and certainly not substances.

[136] On the other hand, Y. Karunadasa contends that the tradition of realism goes back to the earliest discourses, as opposed to developing only in later Theravada sub-commentaries: If we base ourselves on the Pali Nikayas, then we should be compelled to conclude that Buddhism is realistic.

Some of these figures, such as David Kalupahana, Buddhadasa, and Bhikkhu Sujato, have criticized traditional Theravāda commentators like Buddhaghosa for their doctrinal innovations which differ in significant ways from the early Buddhist texts.

[web 11] Apart from nibbana, there are various reasons why traditional Theravāda Buddhism advocates meditation, including a good rebirth, supranormal powers, combating fear and preventing danger.

Crosby notes that this tradition of meditation involved a rich collection of symbols, somatic methods and visualizations which included "the physical internalisation or manifestation of aspects of the Theravada path by incorporating them at points in the body between the nostril and navel.

[187][188] According to Buswell vipassana, "appears to have fallen out of practice" by the 10th century, due to the belief that Buddhism had degenerated, and that liberation was no longer attainable until the coming of Maitreya.

[191] In Sri Lanka, the new Buddhist traditions of the Amarapura and Rāmañña Nikāyas developed their own meditation forms based on the Pali Suttas, the Visuddhimagga, and other manuals, while borān kammaṭṭhāna mostly disappeared by the end of the 19th century.

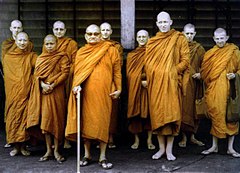

While the possibility of significant attainment by laymen is not entirely disregarded by the Theravāda, it generally occupies a position of less prominence than in the Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions, with monastic life being hailed as a superior method of achieving Nirvana.

Schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism without monastic communities of fully ordained monks and nuns are relatively recent and atypical developments, usually based on cultural and historical considerations rather than differences in fundamental doctrine.

[citation needed] The role of lay people has traditionally been primarily occupied with activities that are commonly termed merit-making (falling under Spiro's category of kammatic Buddhism).

Merit-making activities include offering food and other basic necessities to monks, making donations to temples and monasteries, burning incense or lighting candles before images of the Buddha, chanting protective or scriptural verses from the Pali Canon, building roads and bridges, charity to the needy and providing drinking water to strangers along roadside.

[207] They view themselves as living closer to the ideal set forth by the Buddha, and are often perceived as such by lay folk, while at the same time often being on the margins of the Buddhist establishment and on the periphery of the social order.

In Thailand and Myanmar, young men typically ordain for the retreat during Vassa, the three-month monsoon season, though shorter or longer periods of ordination are not rare.

In many Southeast Asian cultures, it is seen as a means for a young man to "repay his gratitude" to his parents for their work and effort in raising him, because the merit from his ordination is dedicated for their well-being.

In countries where Buddhism is deeply rooted, it can often be easier to adhere to the lifestyle of a monk or nun, as it requires considerable discipline to successfully live by the non-secular rules and regulations for which Buddhist practices are known.

In the Buddhist society of Sri Lanka, most monks spend hours every day in taking care of the needs of lay people such as preaching bana,[212] accepting alms, officiating funerals, teaching dhamma to adults and children in addition to providing social services to the community.

In contemporary society, these teachings inspire individuals and organizations to prioritize social responsibility, charitable activities, and humanitarian efforts aimed at alleviating suffering and promoting the welfare of others.