Thin-film interference

When white light is incident on a thin film, this effect produces colorful reflections.

Thin-film interference explains the multiple colors seen in light reflected from soap bubbles and oil films on water.

Therefore, the colors observed are rarely those of the rainbow, but rather browns, golds, turquoises, teals, bright blues, purples, and magentas.

Thin films have many commercial applications including anti-reflection coatings, mirrors, and optical filters.

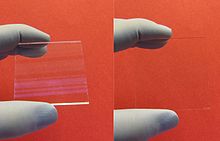

In optics, a thin film is a layer of material with thickness in the sub-nanometer to micron range.

The Fresnel equations provide a quantitative description of how much of the light will be transmitted or reflected at an interface.

The degree of constructive or destructive interference between the two light waves depends on the difference in their phase.

Consider light incident on a thin film and reflected by both the upper and lower boundaries.

The optical path difference (OPD) of the reflected light must be calculated in order to determine the condition for interference.

Interference will be constructive if the optical path difference is equal to an integer multiple of the wavelength of light,

As the thickness of the film varies from one location to another, the interference may change from constructive to destructive.

Further reduction in reflection is possible by adding more layers, each designed to match a specific wavelength of light.

[1] The glossy appearance of buttercup flowers is also due to a thin film[2][3] as well as the shiny breast feathers of the bird of paradise.

They can be engineered to control the amount of light reflected or transmitted at a surface for a given wavelength.

A Fabry–Pérot etalon takes advantage of thin film interference to selectively choose which wavelengths of light are allowed to transmit through the device.

These films are created through deposition processes in which material is added to a substrate in a controlled manner.

Many animals have a layer of tissue behind the retina, the Tapetum lucidum, that aids in light collecting.

In a typical ellipsometry experiment polarized light is reflected off a film surface and is measured by a detector.

A model analysis is then conducted, in which the information is used to determine film layer thicknesses and refractive indices.

Dual polarisation interferometry is an emerging technique for measuring refractive index and thickness of molecular scale thin films and how these change when stimulated.

Iridescence caused by thin-film interference is a commonly observed phenomenon in nature, being found in a variety of plants and animals.

In Micrographia, Hooke postulated that the iridescence in peacock feathers was caused by thin, alternating layers of plate and air.

Young's contribution went largely unnoticed until the work of Augustin Fresnel, who helped to establish the wave theory of light in 1816.

[6] However, very little explanation could be made of the iridescence until the 1870s, when James Maxwell and Heinrich Hertz helped to explain the electromagnetic nature of light.

[5] After the invention of the Fabry–Perot interferometer, in 1899, the mechanisms of thin-film interference could be demonstrated on a larger scale.

[6] In much of the early work, scientists tried to explain iridescence, in animals like peacocks and scarab beetles, as some form of surface color, such as a dye or pigment that might alter the light when reflected from different angles.

[7] In 1925, Ernest Merritt, in his paper A Spectrophotometric Study of Certain Cases of Structural Color, first described the process of thin-film interference as an explanation for the iridescence.

The first examination of iridescent feathers by an electron microscope occurred in 1939, revealing complex thin-film structures, while an examination of the morpho butterfly, in 1942, revealed an extremely tiny array of thin-film structures on the nanometer scale.

In 1817, Joseph Fraunhofer discovered that, by tarnishing glass with nitric acid, he could reduce the reflections on the surface.

In 1819, after watching a layer of alcohol evaporate from a sheet of glass, Fraunhofer noted that colors appeared just before the liquid evaporated completely, deducing that any thin film of transparent material will produce colors.