Thing (assembly)

[2] The meaning of personal possessions, commonly in the plural, first appears in Middle English around 1300,[3] and eventually led to the modern sense of "object".

[4] The oldest written reference to a thing is on a stone pillar found along Hadrian's Wall at Housesteads Roman Fort in Northumberland in the United Kingdom.

It is dated 43–410 CE and reads: DEO MARTI THINCSO ET DUABUS ALAISIAGIS BEDE ET FIMMILENE ET N AUG GERM CIVES TUIHANTI VSLMTo the god Mars Thincsus and the two Alaisiagae, Beda and Fimmilena, and to the Divinity of the Emperor the Germanics, being tribesmen of Tuihanti, willingly and deservedly fulfilled their vow.The pillar was raised by a Frisian auxiliary unit of the Roman army deployed at Hadrian's Wall.

The god Tīwaz (Old English Tíw, Old Norse Týr) was likely important in early Germanic times and has numerous places in England and Denmark named after him.

The possible theonyms Beda and Fimmilena in the same inscription relate to the bodthing and fimelthing, two specific types of assemblies were recorded in Old Frisian codices from around 1100 onward.

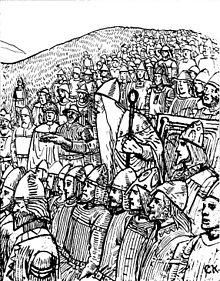

In the Viking Age, things were the public assemblies of the free men of a country, province, or a hundred (Swedish: härad, hundare, Danish: herred).

However, things are in a more general sense, balancing structures used to reduce tribal feuds and avoid social disorder in North Germanic cultures.

They played an essential role in Viking society as forums for conflict resolution, marriage alliances, power display, honor, and inheritance settlements.

[11] Specifically in Scandinavia, unusually large runestones and inscriptions suggesting a local family's attempt to claim supremacy are standard features of thingsteads.

[13] While the things were not democratic assemblies in the modern sense of an elected body, they were built around ideas of neutrality and representation,[13] effectively representing the interests of larger numbers of people.

In Norway, the thing was a space where free men and elected officials met and discussed matters of collective interest, such as taxation.

[15] History professor Torgrim Titlestad describes how Norway, with the thing sites, displayed an advanced political system over a thousand years ago, one that was characterized by high participation and democratic ideologies.

Today, few thingsteads from Norway are known for sure, and as new assembly sites are found, scholars question whether these are old jurisdiction districts which the king used as a foundation for his organization or whether he created new administrative units.

"[19] Since the record of Norwegian thing sites is not comprehensive, it is not favorable to rely on archeological and topographical characteristics to determine whether they were established before the state-formation period.

This view is based partly on Norse sagas' narratives of Viking chieftains and the distribution of large grave mounds.

[21] Based on what is known from later medieval documents, one deep-rooted custom of Norwegian law areas was the bearing of arms coming from the old tradition of the wapentake "weapon-take", which refers to the rattling of weapons at meetings to agree.

[23] Similar to Norway, thing sites in Sweden experienced changes in administrative organization beginning in the late tenth and eleventh century.

[24] Swedish assembly sites could be characterized by several typical features: large mounds, rune-stones, and crossings between roads by land or water to allow for greater accessibility.

The island of Gotland had twenty things in late medieval times, each represented at the island-thing called landsting by its elected judge.

Unlike other European societies in the Middle Ages, Iceland was unique for relying on the Althing's legislative and judicial institutions at the national level rather than an executive branch of government.

[26] Þingvellir was the site of the Althing, and it was a place where people came together once a year to bring cases to court, render judgments, and discuss laws and politics.

[27] At the annual Althing, the thirty-nine goðis along with nine others served as voting members of the Law Council (Lögrétta), a legislative assembly.

At Upstalsboom, near the current town of Aurich in the East Frisia region, Germany, delegates and judges from all seven Frisian sealands used to gather once a year.

The assembly of things were typically held at a specially designated place, often a field or common, like Þingvellir, the old location of the Icelandic Alþing.

Other equivalent place names can be found across northern Europe: in Scotland, there is Dingwall in the Scottish Highlands and Tingwall, occurring both in Orkney and Shetland, and further south there is Tinwald, in Dumfries and Galloway and – in England – Thingwall, a village on the Wirral Peninsula.

Þingvellir was thought of as a trading place as a result of saga passages and law texts that refer to trade: As shown in the Laxdæla saga, meetings at Þingvellir required people to travel from long distances and gather together for an extended period, thus it was inevitable that entertainment, food, tools, and other goods would have played a role in the gatherings.

Research on Scandinavian trade and assembly is burgeoning, and thus far evidence has mostly been found in written sources, such as the sagas, and place names, "such as the 'Disting' market that is said to have been held during the thing meetings at Gamla Uppsala in Sweden.

"[34] The national legislatures of Iceland, Norway and Denmark all have names that incorporate thing: The legislatures of the self-governing territories of Åland, Faroe Islands, Greenland and Isle of Man also have names that refer to thing: In addition, thing can be found in the name of the Swedish Assembly of Finland (Svenska Finlands folkting), a semi-official body representing the Finland Swedish, and those of the three distinct elected Sámi assemblies which are all called Sameting in Norwegian and Swedish (Northern Sami Sámediggi).

A constitutional amendment passed in February 2007 abolished the Lagting and Odelsting, making this de facto unicameralism official following the 2009 election.