Thomas Hart Benton (politician)

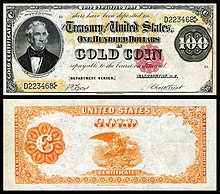

Thomas Hart Benton (March 14, 1782 – April 10, 1858), nicknamed "Old Bullion", was an American politician, attorney, soldier, and longtime United States senator from Missouri.

Benton won election to the United States House of Representatives in 1852 but was defeated for re-election in 1854 after he opposed the Kansas–Nebraska Act.

Thomas H. Benton also studied law at the University of North Carolina[5] where he was a member of the Philanthropic Society, but in 1799 he was dismissed from school after admitting to stealing money from fellow students.

[citation needed] Attracted by the opportunities in the West, the young Benton moved the family to a 40,000 acre (160 km2) holding near Nashville, Tennessee.

[citation needed] In 1804, Benton worked as a clerk or "factor" at Gordon's Ferry on the Duck River stop on the Natchez Trace.

Benton was assigned to represent Jackson's interests to military officials in Washington D.C.; he chafed under the position, which denied him combat experience.

He settled in St. Louis, where he practiced law and edited the Missouri Enquirer, the second major newspaper west of the Mississippi River.

According to James D. Davis' 1873 history of Memphis, Benton returned from the War of 1812 "with a beautiful French quadroon girl, with whom he lived some two or three years.

[15] Benton also purchased a 12-year-old enslaved girl named Phoebe Moore and resold her when she was 16 to Henry Clay, who kept her as a concubine and fathered her two children.

The presidential election of 1824 was a four-way struggle between Jackson, John Quincy Adams, William H. Crawford, and Henry Clay.

Jackson received a plurality but not a majority of electoral votes, meaning that the election was thrown to the House of Representatives, which would choose among the top three candidates.

He said that "the peace of eleven states in this Union will not permit the fruits of a successful negro insurrection to be exhibited among them" and said whites in the south would "not permit black Consuls and Ambassadors to establish themselves in our cities, and to parade through our country, and give their fellow blacks in the United States, proof in hand of the honors which await them, for a like successful effort on their part.

[22] At the close of the Jackson presidency, Benton led a successful "expungement campaign" in 1837 to remove the censure motion from the official record.

"Soft" (i.e. paper or credit) currency, in his opinion, favored rich urban Easterners at the expense of the small farmers and tradespeople of the West.

He proposed a law requiring payment for federal land in hard currency only, which was defeated in Congress but later enshrined in an executive order, the Specie Circular, by Jackson (1836).

[24] Senator Benton's greatest concern, however, was the territorial expansion of the United States to meet its "manifest destiny" as a continental power.

Benton was the author of the first Homestead Acts, which encouraged settlement by giving land grants to anyone willing to work the soil.

He was an orator and leader of the first class, able to stand his own with or against fellow senators Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun.

On February 28, 1844, Benton was present at the USS Princeton explosion when a cannon misfired on the deck while giving a tour of the Potomac River.

He was also at odds with fellow Democrats, such as John C. Calhoun, who he thought put their opinions ahead of the Union to a treasonous degree.

The memoirs of a long-time Washington resident described the man and the decline in his electoral appeal over time: "Colonel Thomas Hart Benton, who had earned his military title during the war with Great Britain, was a large, heavily-framed man, with black curly hair and whiskers, prominent features and a stentorian voice.

He wore the high, black silk neck-stock and the double-breasted frock coat of his youthful times during his thirty years' career in the Senate, varying with the seasons the materials of which his pantaloons were made, but never the fashion in which they were cut.

When in debate, outraging every customary propriety of language, he would rush forward with blind fury upon every obstacle like the huge wild buffaloes then ranging the prairies of his adopted State, whose paths, be used to subsequently assert, would show the way through the passes of the Rocky Mountains.

In private life Colonel Benton was gentleness and domestic affection personified, and a desire to have his children profit by the superior advantages for their education in the District of Columbia kept him from his constituents in Missouri, where a new generation of voters grew up who did not know him and who would not follow his political lead.

"[25] In 1851, Benton was denied a sixth term by the Missouri legislature; the polarization of the slavery issue made it impossible for a moderate and Unionist to hold that state's senatorial seat.

Seven states (Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Oregon, and Washington) have counties named after Benton.

[32] In July 2018, the president of Oregon State University, Ed Ray, announced that three campus buildings would be renamed due to their namesakes' racism.

At the beginning of chapter XXII it states: Even the Glorious Fourth was in some sense a failure, for it rained hard, there was no procession in consequence, and the greatest man in the world (as Tom supposed), Mr. Benton, an actual United States Senator, proved an overwhelming disappointment—for he was not twenty-five feet high, nor even anywhere in the neighborhood of it.