Thymus

The thymus is an organ that sits behind the sternum in the upper front part of the chest, stretching upwards towards the neck.

[5] It is made up of two lobes that meet in the upper midline, and stretch from below the thyroid in the neck to as low as the cartilage of the fourth rib.

[3] The thymus lies behind the sternum, rests on the pericardium, and is separated from the aortic arch and great vessels by a layer of fascia.

[1] The thymus consists of two lobes, merged in the middle, surrounded by a capsule that extends with blood vessels into the interior.

[4] The lobes are divided into smaller lobules 0.5-2 mm diameter, between which extrude radiating insertions from the capsule along septa.

This network forms an adventitia to the blood vessels, which enter the cortex via septa near the junction with the medulla.

[3] These extend outward and backward into the surrounding mesoderm and neural crest-derived mesenchyme in front of the ventral aorta.

The pharyngeal opening of each diverticulum is soon obliterated, but the neck of the flask persists for some time as a cellular cord.

[4] Fat cells are present at birth, but increase in size and number markedly after puberty, invading the gland from the walls between the lobules first, then into the cortex and medulla.

[4] This process continues into old age, where whether with a microscope or with the human eye, the thymus may be difficult to detect,[4] although typically weighs 5–15 grams.

[3] Additionally, there is an increasing body of evidence showing that age-related thymic involution is found in most, if not all, vertebrate species with a thymus, suggesting that this is an evolutionary process that has been conserved.

[17] The most common congenital cause of thymus-related immune deficiency results from the deletion of the 22nd chromosome, called DiGeorge syndrome.

[16] A number of genetic defects can cause SCID, including IL-2 receptor gene loss of function, and mutation resulting in deficiency of the enzyme adenine deaminase.

[18] Specifically, the disease results from defects in the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) gene, which stimulates expression of self antigens in the epithelial cells within the medulla of the thymus.

[18] People with APECED develop an autoimmune disease that affects multiple endocrine tissues, with the commonly affected organs being hypothyroidism of the thyroid gland, Addison's disease of the adrenal glands, and candida infection of body surfaces including the inner lining of the mouth and of the nails due to dysfunction of TH17 cells, and symptoms often beginning in childhood.

This is because the malignant thymus is incapable of appropriately educating developing thymocytes to eliminate self-reactive T cells.

[19] Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disease most often due to antibodies that block acetylcholine receptors, involved in signalling between nerves and muscles.

[21] Myasthenia gravis most often develops between young and middle age, causing easy fatiguing of muscle movements.

[20] Investigations include demonstrating antibodies (such as against acetylcholine receptors or muscle-specific kinase), and CT scan to detect thymoma or thymectomy.

[20] Other treatments include increasing the duration of acetylcholine action at nerve synapses by decreasing the rate of breakdown.

Genetic analysis including karyotyping may reveal specific abnormalities that may influence prognosis or treatment, such as the Philadelphia translocation.

[25] Most often, when symptoms occur it is because of compression of structures near the thymus, such as the superior vena cava or the upper respiratory tract; when lymph nodes are affected it is often in the mediastinum and neck groups.

[26] Despite this, the presence of a cyst can cause problems similar to those of thymomas, by compressing nearby structures,[3] and some may contact internal walls (septa) and be difficult to distinguish from tumours.

[2] In neonates the relative size of the thymus obstructs surgical access to the heart and its surrounding vessels.

[2][28] In older children and adults, which have a functioning lymphatic system with mature T cells also situated in other lymphoid organs, the effect is reduced, but includes failure to mount immune responses against new antigens,[2] an increase in cancers, and an increase in all-cause mortality.

[33] In the 19th century, a condition was identified as status thymicolymphaticus defined by an increase in lymphoid tissue and an enlarged thymus.

[34] The importance of the thymus in the immune system was discovered in 1961 by Jacques Miller, by surgically removing the thymus from one-day-old mice, and observing the subsequent deficiency in a lymphocyte population, subsequently named T cells after the organ of their origin.

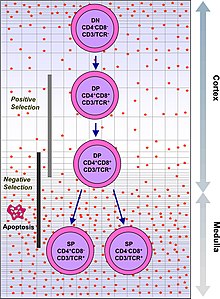

[14] Recently, advances in immunology have allowed the function of the thymus in T-cell maturation to be more fully understood.

Recently, in 2011, a discrete thymus-like lympho-epithelial structure, termed the thymoid, was discovered in the gills of larval lampreys.

[39] As in humans, the guinea pig's thymus naturally atrophies as the animal reaches adulthood,[40] but the athymic hairless guinea pig (which arose from a spontaneous laboratory mutation) possesses no thymic tissue whatsoever, and the organ cavity is replaced with cystic spaces.