Tilbury Fort

The earliest version of the fort, comprising a small blockhouse with artillery covering the river, was constructed by King Henry VIII to protect London against attack from France as part of his Device programme.

Following naval raids during the Anglo-Dutch Wars, the fort was enlarged by Sir Bernard de Gomme from 1670 onwards to form a star-shaped defensive work, with angular bastions, water-filled moats and two lines of guns facing onto the river.

[2] The first permanent fortification at Tilbury in Essex was built as a consequence of international tensions between England, France and the Holy Roman Empire in the final years of the reign of King Henry VIII.

Traditionally the Crown had left coastal defences to the local lords and communities, only taking a modest role in building and maintaining fortifications, and while France and the Empire remained in conflict with one another, maritime raids were common but an actual invasion of England seemed unlikely.

[3] Basic defences, based around simple blockhouses and towers, existed in the south-west and along the Sussex coast, with a few more impressive works in the north of England, but in general the fortifications were very limited in scale.

[8] In response, Henry issued an order, called a "device", in 1539, giving instructions for the "defence of the realm in time of invasion" and the construction of forts along the English coastline.

[9] The River Thames was strategically important, as the city of London and the newly constructed royal dockyards of Deptford and Woolwich were vulnerable to seaborne attacks arriving up the estuary, which was a major maritime route, carrying 80 per cent of England's exports.

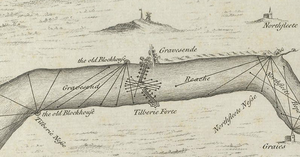

[13] Under the King's new programme of work, the Thames was protected with a mutually reinforcing network of blockhouses at Gravesend, Milton, and Higham on the south side of the river, and West and East Tilbury on the opposite bank.

[18] It was initially commanded by Captain Francis Grant and his deputy, and garrisoned with a porter, two soldiers and four gunners, equipped with up to five artillery pieces including a demi-cannon and sakers.

[21] An army was mobilised to protect the mouth of the estuary and emergency improvements to the fortifications at Tilbury Blockhouse were made by Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester.

[22] Queen Elizabeth I visited the fort by barge on 8 August 1588 and rode in procession to the nearby army camp, where she gave a speech to the assembled forces.

[23] Fears of invasion continued even after the defeat of the Armada, and over the course of the next year the Italian engineer, Federigo Giambelli, reinforced the blockhouse with probably two concentric earthwork ramparts, with ditches and a palisade.

[29] In the wake of the conflict, the King instructed his Chief Engineer, a Dutchman called Sir Bernard de Gomme, to develop Tilbury Fort's defences further.

[35][a] The result was a large, five-sided, star-shaped fort with four angular bastions, revetted in brick, with an outer curtain of defences, including two moats and a redoubt; two new gatehouses defended the entrance from the north.

[39] A trader called a sutler built a house inside the southern entrance, growing vegetables within the south-west bastion and enjoying an effective monopoly on selling food to the soldiers.

[52] Tilbury continued to be an essential part of the capital's defences because of its control of the crossing point on the Thames, and the guns were upgraded with new traversing platforms; the Gravesend Volunteer Artillery was formed to man the forts on both sides of the river.

[53] During the invasion scare of 1803, the Royal Trinity House Volunteer Artillery manned ten armed hulks placed across the river as a barrier at Tilbury.

[55] Despite the construction of a new range of facilities in 1809, the living conditions of the soldiers remained poor, with four men sharing each of the two-bed rooms in the barracks, and no running water on the site.

[57] Nationwide investigations into the standard of Army barracks during 1857 led to investment in better facilities at Tilbury; piped water was run into the site in 1877, and improved amenities and sanitation were installed after 1880.

[60] Work began on strengthening Tilbury in 1868, under the direction of the then Captain Charles Gordon, focusing on adding heavier gun positions able to fire upstream to support the new forts.

[64] From 1889 onwards it formed a mobilisation centre to support a mobile strike force in the event of an invasion, part of the wider London Defence Scheme, and large storage buildings were built across the site to store materiel.

[67] Tilbury continued to function as a mobilisation store and, after the outbreak of the First World War, it was used to house up to 300 transit soldiers and to supply the new army camps established at Purfleet and Belhus Mansion.

[73] During the Second World War, the fort initially housed an improvised anti-aircraft operations room, controlling the defences of the Thames and Medway (North) Gun Zone between 1939 and 1940.

[84] There are bastions on the north-west and north-east corners, and two triangular spurs, originally equipped with cannons, project from the defences on the west and east sides, with assembly points for infantry soldiers on the inside.

[88] A sluice gate in the south-west corner managed the water in the moats, and allowed them to be drained completely should the surfaces begin to freeze over in winter and provide an advantage to any attackers.

This two-storeyed gatehouse dates from the late 17th century with a monumental stone facade featuring carved displays of classical and 17th-century weapons; when first built, the now-empty niche at the front probably held a statue of King Charles II.

[94] Facing the parade ground are the officers' quarters, a terrace of houses probably dating in its current form to the late 18th century, with a stables at the northern end, originally used to hold the commandant's horses.

[101] Just to the west of the Water Gate is the fort's guardhouse and chapel, dating from the late 17th century and one of the oldest surviving places of worship within a British artillery fortress.