Times New Roman

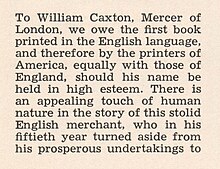

Asked to advise on a redesign, Morison recommended that The Times change their body text typeface from a spindly nineteenth-century face to a more robust, solid design, returning to traditions of printing from the eighteenth century and before.

The paper subsequently has switched typefaces five times between 1972 and 2007 to different variants of the original due to new production techniques and a format change from broadsheet to tabloid in 2004.

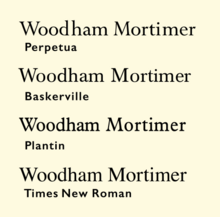

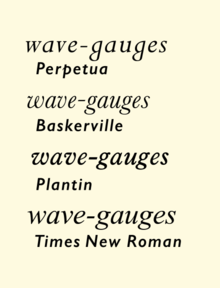

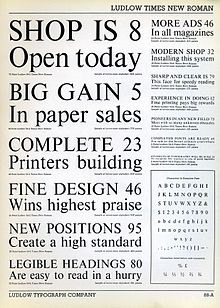

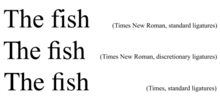

[3][a] As a typeface designed for newspaper printing, Times New Roman has a high x-height, short descenders to allow tight linespacing and a relatively condensed appearance.

[5][b] (Although Hutt,[6] and most other authors, describe Times New Roman as having a higher x-height than Plantin, Tracy reports based on published Monotype dimensions that in the original small metal-type sizes the difference was not great.

[7]) The roman style of Plantin was loosely based on a metal type created in the late sixteenth century by the French artisan Robert Granjon and preserved in the collection of the Plantin-Moretus Museum of Antwerp.

[15] However, Times New Roman modifies the Granjon influence further than Plantin due to features such as its 'a' and 'e', with very large counters and apertures, its ball terminal detailing, a straight-sided 'M' and an increased level of contrast between thick and thin strokes, so it has often been compared to fonts from the late eighteenth century, the so-called 'transitional' genre, in particular the Baskerville typeface of the 1750s.

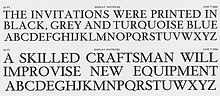

"[21][22][23] Morison had several years earlier attracted attention for promoting the radical idea that italics in book printing were too disruptive to the flow of text, and should be phased out.

[24][25] He rapidly came to concede that the idea was impractical, and later wryly commented to historian Harry Carter that 'Times italic' "owes more to Didot than dogma.

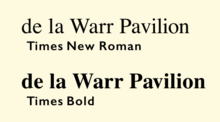

"[26][27][d] Rather than creating a companion boldface with letterforms similar to the roman style, Times New Roman's bold has a different character, with a more condensed and more upright effect caused by making the horizontal parts of curves consistently the thinnest lines of each letter, and making the top serifs of letters like 'd' purely horizontal.

"[38] According to Mosley and Williamson the modern-face used by The Times was Monotype's Series 7 or "Modern Extended", based on typefaces by Miller and Richard.

[41][g] In 1925, the Mergenthaler Linotype Company, Monotype's main competitor, launched a new newspaper typeface called Ionic, which became the first in a series known as the Legibility Group.

[46] The development of Times New Roman was relatively involved due to the lack of a specific pre-existing model – or perhaps a surfeit of possible choices.

Bulked-up versions of Monotype's pre-existing but rather dainty Baskerville and Perpetua typefaces were considered for a basis, and the Legibility Group designs were also examined.

(Perpetua, which Monotype had recently commissioned from sculptor Eric Gill at Morison's urging, is considered a 'transitional' design in aesthetic, although it does not revive any specific model.)

Walter Tracy, who knew Lardent, suggested in the 1980s that "Morison did not begin with a clear vision of the ultimate type, but felt his way along.

[i] Morison's several accounts of his reasoning in designing the concept of Times New Roman were somewhat contradictory and historians of printing have suggested that in practice they were mostly composed to rationalise his pre-existing aesthetic preferences: after Morison's death Allen Hutt went so far as to describe his unsigned 1936 article on the topic[3] as "rather odd...it can only be regarded as a piece of Morisonian mystification".

Morison told his friend Ellic Howe that the test type sent to him just before the war was sent to the government to be "analysed in order that we should know whether the Hun is hard up for lead or antimony or tin.

[86][40]) An early user of Times New Roman outside its origin was by Daniel Berkeley Updike, an influential historian of printing with whom Morison carried an extensive correspondence.

[29][k] Hutt also commented that Times New Roman's relative condensation was less useful than might be expected for newspaper printing, since in a normal newspaper column frequent paragraph breaks tend to provide area that can absorb the space of wider letters without increasing the number of lines used–but The Times, whose house style in the 1930s was to minimise the number of paragraph breaks, was an exception to this.

[97] Most were appreciative (Morison was an influential figure in publishing) but several noted that it did not follow conventional expectations of newspaper typeface design.

"[42] Times New Roman remains popular in publishing, helped by the extremely large range of characters available for international and mathematics printing.

[102][103] The Australian Government logo used Times New Roman Bold as a wordmark for departments and agencies are required to use common branding on their websites and print publications.

[104] Monotype originally created Times New Roman for its typesetting machines, but its rival Linotype rapidly began to offer its version of the typeface with subtle differences.

[109] Linotype licensed its version to Xerox and then Adobe and Apple, guaranteeing its importance in digital printing by making it one of the core fonts of the PostScript page description language.

[144][145] Giampa asked Parker to complete the type from the limited number of surviving letters, which was issued in June 2009 by Font Bureau under the name of 'Starling'.

[27][146][147] Reception to the claims was sceptical, with dismissal from Morison's biographer Nicolas Barker and Luc Devroye among others; Barker suggested that the material had been fabricated in order to aid Giampa in embarrassing Monotype's British branch, while Devroye and Thomas Phinney of FontLab suggested that the claim had begun as a prank.

[145][51][148][149] In 2010, Mark Owens[150] described Parker's article in retrospect as "the scantest of evidence" and a "fog of irrelevant details"[151] and Simon Loxley that it "doesn't really have a leg to stand on".

[152][l] Monotype executive Dan Rhatigan described the theory as implausible in 2011: "I'll admit that I tend to side with the more fully documented (both in general, and in agreement with what little I can find within Monotype to support it) notion that Times New Roman was based on Plantin...I won't rule out the possibility that Starling Burgess drew up the concept first, but Occam's razor makes me doubt it.

"[86] The Times Online web site credits the design to "Stanley Morrison, Victor Lardent and perhaps Starling Burgess".

[170][171][172][173] Some fonts intended for typesetting multiple writing systems use Times New Roman as a model for Latin-alphabet glyphs: