Tiwanaku Empire

[2] Its capital was the monumental city of Tiwanaku, located at the center of the polity's core area in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin.

[5] Tiwanaku grew into the Andes' most important pilgrimage destination and one of the continent's largest Pre-Columbian cities, reaching a maximum population of 10,000 to 20,000 around AD 800.

The city of Tiwanaku lies at an altitude of roughly 3,800 meters (12,500 feet) above sea level, making it the highest state capital of the ancient world.

[6] The site of Tiwanaku was founded around 110 AD during the Late Formative Period, when there were a number of growing settlements in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin.

[2] Beginning around 600 AD its population grew rapidly, probably due to a massive immigration from the surrounding countryside, and large parts of the city were built or remodeled.

[3] New and larger carved monoliths were erected, temples were built, and a standardized polychrome pottery style was produced on a large scale.

William H. Isbell states that "Tiahuanaco underwent a dramatic transformation between 600 and 700 that established new monumental standards for civic architecture and greatly increased the resident population.

[14] In this view of Tiwanaku as a bureaucratic state, elites controlled the economic output, but were expected to provide each commoner with all the resources needed to perform his or her function.

Tiwanaku's location between the lake and dry highlands provided key resources of fish, wild birds, plants, and herding grounds for camelids, particularly llamas.

[16] Tiwanaku's economy was based on exploiting the resources of Lake Titicaca, herding of llamas and alpacas, and organized farming in raised field systems.

Because of the variable climate in the high altitude regions, the storability of food became important, prompting the development of technologies for freeze-dried potatoes and sun-dried meat.

This led independent researchers like Bandy (2005) to suggest that raised fields were not in fact hyper-productive, noting that local people did not continue using them once experiments and development programs ended in the 1990s.

[23] Around 1000 AD, Tiwanaku ceramics stopped being produced as the state's largest colony (Moquegua) and the urban core of the capital were abandoned within a few decades.

One proposed explanation is that a severe drought rendered the raised-field systems ineffective, food surplus dropped, and with it, elite power, leading to state collapse.

[27] It has been conjectured that the collapse of the Tiwanaku empire caused a southward migratory wave leading to a series of changes in Mapuche society in Chile.

[28] Tom Dillehay and co-workers suggest that the decline of Tiwanaku would have led to the spread of agricultural techniques into Mapuche lands in south-central Chile.

... dispersing populations in search of new suitable environments might have caused long-distance ripple effects of both migration and technological diffusion across the south-central and south Andes between c.AD 1100 and 1300 ...What is known of Tiwanaku religious beliefs is based on archaeological interpretation and some myths, which may have been passed down to the Incas and the Spanish.

This statue is believed to be associated with the weather: a celestial high god that personified various elements of natural forces intimately associated the productive potential of altiplano ecology: the sun, wind, rain, hail – in brief, a personification of atmospherics that most directly affect agricultural production in either a positive or negative manner[10] It has twelve faces covered by a solar mask, and at the base thirty running or kneeling figures.

The type of human sacrifice included victims being hacked in pieces, dismembered, exposed to the elements and carnivores before being deposited in trash.

[27] Research showed that one man who was sacrificed was not a native to the Titicaca Basin, leaving room to think that sacrifices were most likely of people originally from other societies.

In contrast to the masonry style of the later Inca, Tiwanaku stone architecture usually employs rectangular ashlar blocks laid in regular courses.

The drainage systems of the Akapana and Pumapunku structures include conduits composed of red sandstone blocks held together by ternary (copper/arsenic/nickel) bronze architectural cramps.

The red sandstone used in this site's structures has been determined by petrographic analysis to come from a quarry 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) away—a remarkable distance considering that the largest of these stones weighs 131 metric tons.

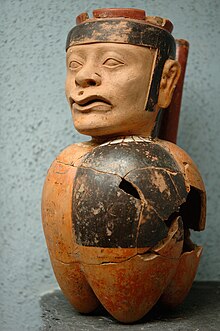

[34] Tiwanaku sculpture is comprised typically of blocky, column-like figures with huge, flat square eyes, and detailed with shallow relief carving.

Later the Qeya style became popular during the Tiwanaku III phase, "Typified by vessels of a soft, light brown ceramic paste".

Such small, portable objects of ritual religious meaning were a key to spreading religion and influence from the main site to the satellite centers.

They were created in wood, engraved bone, and cloth and included incense burners, carved wooden hallucinogenic snuff tablets, and human portrait vessels.

Radiocarbon dating revealed that they were interred in the ground between 900 and 1050 AD, so they were probably broken as part of a ritual abandonment of the island's temple by local elites and pilgrims during the collapse of Tiwanaku.

The Tiwanaku shared domination of the Middle Horizon with the Wari culture (based primarily in central and south Peru) although found to have built important sites in the north as well (Cerro Papato ruins).

Significant elements of both of these styles (the split eye, trophy heads, and staff-bearing profile figures, for example) seem to have been derived from that of the earlier Pukara culture in the northern Titicaca Basin.