Yuezhi

[13] The Greater Yuezhi initially migrated northwest into the Ili Valley (on the modern borders of China and Kazakhstan), where they reportedly displaced elements of the Sakas.

The Greater Yuezhi have consequently often been identified with peoples mentioned in classical European sources as having overrun the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, like the Tókharoi[d] and Asii.

The subsequent Kushan Empire, at its peak in the 3rd century AD, stretched from Turfan in the Tarim Basin in the north to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain of India in the south.

Some are reported to have settled among the Qiang people in Qinghai, and to have been involved in the Liang Province Rebellion (184–221 AD) against the Eastern Han dynasty.

A fourth group of Lesser Yuezhi may have become part of the Jie people of Shanxi, who established the Later Zhao state of the 4th century AD (although this remains controversial).

[23][24] This is probably the first reference to the Yuezhi as a lynchpin in trade on the Silk Road,[25] which in the 3rd century BC began to link Chinese states to Central Asia and, eventually, the Middle East, the Mediterranean and Europe.

Essentially the same text appears in chapter 61 of the Book of Han, though Sima Qian has added occasional words and phrases to clarify the meaning.

They have thus placed the original homeland of the Yuezhi 1,000 km further northwest in the grasslands to the north of the Tian Shan (in the northern part of modern Xinjiang).

Shortly before 176 BC, led by one of Modu's tribal chiefs, the Xiongnu invaded Yuezhi territory in the Gansu region and achieved a crushing victory.

[33][34] Modu boasted in a letter (174 BC) to the Han emperor[35] that due to "the excellence of his fighting men, and the strength of his horses, he has succeeded in wiping out the Yuezhi, slaughtering or forcing to submission every number of the tribe."

The son of Modu, Laoshang Chanyu (ruled 174–166 BC), subsequently killed the king of the Yuezhi and, in accordance with nomadic traditions, "made a drinking cup out of his skull."

"[41] In 132 BC the Wusun, in alliance with the Xiongnu and out of revenge from an earlier conflict, again managed to dislodge the Yuezhi from the Ili Valley, forcing them to move south-west.

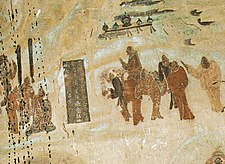

Zhang Qian, who spent a year in Transoxiana and Bactria, wrote a detailed account in the Shiji, which gives considerable insight into the situation in Central Asia at the time.

[43] Zhang Qian also reported: the Great Yuezhi live 2,000 or 3,000 li [832–1,247 kilometers] west of Dayuan, north of the Gui [Oxus ] river.

The capital is called the city of Lanshi and has a market where all sorts of goods are bought and sold.The next mention of the Yuezhi in Chinese sources is found in chapter 96A of the Book of Han (completed in AD 111), relating to the early 1st century BC.

All the kingdoms call [their king] the Guishuang (Kushan) king, but the Han call them by their original name, Da Yuezhi.A later Chinese annotation in Zhang Shoujie's Shiji (quoting Wan Zhen 萬震 in Nánzhōuzhì 南州志 ["Strange Things from the Southern Region"], a now-lost 3rd-century text from the Wu kingdom), describes the Kushans as living in the same general area north of India, in cities of Greco-Roman style, and with sophisticated handicraft.

The quotes are dubious, as Wan Zhen probably never visited the Yuezhi kingdom through the Silk Road, though he might have gathered his information from the trading ports in the coastal south.

Local products, rarities, treasures, clothing, and upholstery are very good, and even India cannot compare with it.The Central Asian people who called themselves Kushana, were among the conquerors of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom during the 2nd century BC,[62] and are widely believed to have originated as a dynastic clan or tribe of the Yuezhi.

The Greek geographer Strabo mentions this event in his account of the central Asian tribes he called "Scythians":[67] All, or the greatest part of them, are nomads.

[67] Both Pompeius and the Roman historian Justin (2nd century AD) record that the Parthian king Artabanus II was mortally wounded in a war against the Tochari in 124 BC.

Following this territorial expansion, the Kushanas introduced Buddhism to northern and northeastern Asia, by both direct missionary efforts and the translation of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese.

[81] The Lushuihu people, who founded the Northern Liang dynasty (397–439), have been theorized by modern researchers to be descendants of the Lesser Yuezhi that intermingled with the Qiang.

[85] A Chinese monk named Gao Juhui, who traveled to the Tarim Basin in the 10th century, described the Zhongyun (仲雲; Wade–Giles Tchong-yun) as descendants of the Lesser Yuezhi.

Whatever their fate may have been, the Xiao Yuezhi ceased to be identifiable by that name and appear to have been subsumed by other ethnicities, including Tibetans, Uyghurs and Han.

[89] Mallory and Mair suggest that the Yuezhi and Wusun were among the nomadic peoples, at least some of whom spoke Iranian languages, who moved into northern Xinjiang from the Central Asian steppe in the 2nd millennium BC.

[90] Scholars such as Edwin Pulleyblank, Josef Markwart, and László Torday, suggest that the name Iatioi—a Central Asian people mentioned by Ptolemy in Geography (AD 150)—may also be an attempt to render Yuezhi.

[91] There has been only limited scholarly support for a theory developed by W. B. Henning, who proposed that the Yuezhi were descended from the Guti (or Gutians) and an associated, but little known tribe known as the Tukri, who were native to the Zagros Mountains (modern Iran and Iraq), during the mid-3rd millennium BC.

In addition to phonological similarities between these names and *ŋʷjat-kje and Tukhāra, Henning pointed out that the Guti could have migrated from the Zagros to Gansu,[92] by the time that the Yuezhi entered the historical record in China, during the 1st millennium BC.

[89] When manuscripts dating from the 6th to 8th centuries AD written in two hitherto unknown Indo-European languages were discovered in the northern Tarim Basin, the early 20th-century linguist Friedrich W. K. Müller identified them with the enigmatic "twγry ("Toγari") language" used to translate Indian Buddhist Sanskrit texts and mentioned as the source of an Old Turkic (Uyghur) manuscript.

[65] Another possible endonym of the Yuezhi was put forward by H. W. Bailey, who claimed that they were referred to, in 9th and 10th century Khotan Saka Iranian texts, as the Gara.

Obv: Bust of Heraios, with Greek royal headband.

Rev: Horse-mounted King, crowned with a wreath by the Greek goddess of victory Nike . Greek legend: TVPANNOVOTOΣ HΛOV – ΣΛNΛB – KOÞÞANOY "The Tyrant Heraios, Sanav (meaning unknown), of the Kushans"