Tondo (historical polity)

Early Augustinian chronicler Pedro de San Buenaventura explained this to be an error as early as 1613 in his Vocabulario de la lengua tagala,[20] but historian Vicente L. Rafael notes that the label was nevertheless later adapted by the popular literature of the Spanish colonial era because Spanish language writers of the time did not have the appropriate words for describing the complex power relations on which Maritime Southeast Asian leadership structures were built.

Junker notes that most of the primary written sources for early Philippine history have inherent biases, which creates a need to counter-check their narratives with one another, and with empirical archaeological evidence.

[29] F. Landa Jocano warns that in the case of early Philippine history, it's essential that "even archaeological findings" be carefully interpreted by experts, because these can be misinterpreted if not analyzed in proper context.

[20] Historian Vicente L. Rafael notes, however, that the label was later adapted by the popular literature of the Spanish colonial era anyway because Spanish-language writers of the time did not have the appropriate words for describing the complex power relations on which Maritime Southeast-Asian leadership structures were built.

[42][18] William Henry Scott, citing Augustinian missionary records,[43] notes that Bunao Lakandula had allowed a group of Chinese refugees, fleeing persecution from Japan, to settle there.

[44][18] Although popular portrayals and early nationalist historical texts sometimes depict Philippine paramount rulers, such as those in the Maynila and Tondo polities, as having broad sovereign powers and holding vast territories, critical historiographers such as Jocano,[7]: 160–161 Scott,[5] and Junker[23] explain that historical sources clearly show that paramount leaders, such as the lakans of Tondo and the rajahs of Maynila, exercised only a limited degree of influence, which did not include claims over the barangays[Notes 5] and territories of less-senior datus.

[5] The influence of Tondo and Maynila over the datus of various polities in pre-colonial Bulacan and Pampanga are acknowledged by historical records, and are supported by oral literature and traditions.

The interpretation of Puliran as part of Tondo and Maynila's alliance network is instead implied by the challenge posed by the Pila Historical Society Foundation and local historian Jaime F. Tiongson to Postma's assertions regarding the exact locations of places mentioned in the Laguna copperplate.

[attribution needed] They are ruled by a lakan, which belongs to a caste[contentious label] of Maharlika, were the feudal warrior class in ancient Tagalog society in Luzon, translated in Spanish as hidalgos, and meaning freeman, libres or freedman.

[7] The term for the barangay social groupings refers to the large ships called balangay, which were common on such coastal polities, and is used by present-day scholars to describe the leadership structure of settlements in early Philippine history.

[citation needed] The date indicated on the LCI text says that it was etched in the year 822 of the Saka Era, the month of Waisaka, and the fourth day of the waning moon, which corresponds to Monday, April 21, 900 AD in the Proleptic Gregorian calendar.

There is no evidence that Islam had become a major political or religious force in the region, with Father Diego de Herrera recording that the Moros lived only in some villages and were Muslim in name only.

[24][71] Historians widely agree that the larger coastal polities which flourished throughout the Philippine archipelago in the period immediately prior to the arrival of the Spanish colonizers (including Tondo and Maynila) were "organizationally complex", demonstrating both economic specialization and a level of social stratification which would have led to a local demand for "prestige goods".

Junker notes that significant work still needs to be done in analyzing the internal/local supply and demand dynamics in pre-Spanish era polities, because much of the prior research has tended to focus on their external trading activities.

[5] Junker describes coastal polities of Tondo and Maynila's size as "administrative and commercial centers functioning as important nodes in networks of external and internal trade.

These Chinese immigrants settled in Manila, Pasig included, and in the other ports, which were annually visited by their trade junks, they have cargoes of silk, tea, ceramics, and their precious jade stones.

Augustinian Fray Martin de Rada Legaspi says that the Tagalogs were "more traders than warriors",[54] and Scott notes in a later book (1994)[5] that Maynila's ships got their goods from Tondo and then dominated trade through the rest of the archipelago.

Rice was the staple food of the Tagalog and Kapampangan polities, and its ready availability in Luzon despite variations in annual rainfall was one of the reasons Legaspi wanted to locate his colonial headquarters on Manila bay.

[5] Historical accounts specifically say that Maynila was also known as the "Kingdom of Luzon", but some scholars such as Potet[35] and Alfonso[78] suggest that this exonym may have referred to the larger area of Manila Bay, from Bataan and Pampanga to Cavite, which includes Tondo.

Whatever the case, the two polities' shared alliance network saw both the Rajahs of Maynila and the Lakans of Tondo exercising political influence (although not territorial control) over the various settlements in what are now Bulacan and Pampanga.

[82] The Dutch anthropologist Antoon Postma has concluded that the Laguna Copperplate Inscription contains toponyms that might be corresponding to certain places in modern Philippines; such as Tundun (Tondo); Pailah (Paila, now an enclave of Barangay San Lorenzo, Norzagaray); Binwangan (Binuangan, now part of Obando); and Puliran (Pulilan).

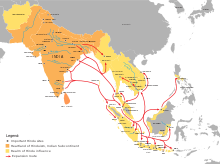

[84][85][verification needed] Theories such as Wilhelm Solheim's Nusantao Maritime Trading and Communication Network (NMTCN) suggest that cultural links between what are now China and the nations of Southeast Asia, including what is now the Philippines, date back to the peopling of these lands.

[86] But the earliest archeological evidence of trade between the Philippine aborigines and China takes the form of pottery and porcelain pieces dated to the Tang and Song dynasties.

[79] Rajah Matanda, then simply known as the "Young Prince" Ache,[80] was raised alongside his cousin, who was ruler of Tondo[79] – presumed by some[80] to be a young Bunao Lakandula, while historian Ian Christopher Alfonso in his 2016 study identifies the unnamed cousin as Malanci or Malangsi,[12] who was mentioned in the "Will of Fernando Malang Balagtas" as the son of Prince Balagtas and Panginoan, who was the uncle and aunt of Ache respectively, thereby corroborating the theory.

[79] In 1521, Prince Ache was coming fresh from a military victory at the helm of the Bruneian navy and was supposedly on his way back to Maynila with the intent of confronting his cousin when he came upon and attacked the remnants of the Magellan expedition, then under the command of Sebastian Elcano.

[21][5][80] De Goiti arrived in mid-1570 and was initially well received by Maynila's ruler Rajah Matanda, who, as former commander of the Naval forces of Brunei, had already had dealings with the Magellan expedition in late 1521.

Negotiations broke down, however, when another ruler, Rajah Sulayman, arrived and began treating the Spanish belligerently, saying that the Tagalog people would not surrender their freedoms as easily as the "painted" Visayans did.

Some historians believe it is more likely that the Maynila forces themselves set fire to their settlement, because scorched-earth retreats were a common military tactic among the peoples of the Philippine archipelago at the time.

[5] De Goiti proclaimed victory, symbolically claimed Maynila on behalf of Spain, then quickly returned to Legaspi because he knew that his naval forces were outnumbered.

"[21][5] As a result of these talks, it was agreed that Lakandula would join De Goiti in an expedition to make overtures of friendship to the various polities in Bulacan and Pampanga, with whom Tondo and Maynila had forged close alliances.