Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

On 19 December 1963, the Defense Secretary Robert McNamara visited Saigon and reported to President Lyndon B. Johnson that the situation was "very disturbing" as "current trends, unless reversed in the next two or three months, will lead to neutralization at best or more likely to a Communist-controlled state.

"[5] McNamara further reported that the Viet Cong were winning the war as they controlled "larger percentages of the population, greater amounts of territory and have destroyed or occupied more strategic hamlets than expected.

[5] In response to McNamara's report, the Joint Chiefs of Staff recommended the United States intervene in the war, with the Air Force's commander, General Curtis LeMay, calling for a strategic bombing campaign against North Vietnam, saying "we are swatting flies when we should be going after the manure pile.

[6] Though Johnson was planning as president to focus on domestic affairs such as civil rights for Afro-Americans together with social legislation to improve the lot of the poor, he was very afraid that to "lose" South Vietnam would cause him to be branded as "soft on Communism", the dreaded accusation that could end the career of any American politician at the time.

In February 1964, Lyman Kirkpatrick, the CIA's Inspector General, visited South Vietnam and reported that he was "shocked by the number of our people and of the military, even those whose job is always to say that we are winning, who feel the tide is against us".

[17] Rostow was supported by William Bundy, assistant secretary for Asia, who advised Johnson in a memo on 01 March 1964 that the U.S Navy should blockade Haiphong and start bombing North Vietnam's railroads, factories, road and training camps.

[19] Bundy argued that the "best answer" to this problem was an event from Johnson's own career as a Senator when, in January 1955, he voted for the Formosa Resolution giving President Eisenhower the power to use military force "as he deems necessary" to protect Taiwan from a Chinese invasion.

[20] Bundy warned the president that his "doubtful friends" in Congress might delay the passage of the desired resolution which would give America's European allies opposed to a war in Southeast Asia the chance to impose "tremendous pressure" on the U.S. "to stop and negotiate".

[23] McNamara further reported that desertion rate in the ARVN was "high and increasing"; the Vietcong were "recruiting energetically"; the South Vietnamese people were overcome by "apathy and indifference"; and the "greatest weakness" was the "uncertain viability" of Khánh regime which might be overthrown by another coup at any moment.

[30] On 18 June 1964, the Canadian diplomat J. Blair Seaborn, who served as Canada's representative on the International Control Commission, arrived in Hanoi carrying a secret message from Johnson that North Vietnam would suffer the "greatest devastation" from American bombing if it continued on its present course.

[37] In support of the raids, an American destroyer, the USS Maddox was deployed to the Gulf of Tonkin with orders to collect electronic intelligence on the North Vietnamese radar system.

Breaking contact, the combatants commenced going their separate ways, when the three torpedo boats, T-333, T-336, and T-339 were then attacked by four USN F-8 Crusader jet fighter bombers from the aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga.

Johnson was informed of the incident and -- in the first use of the "hotline" to Moscow installed after the Cuban Missile Crisis -- called Khrushchev in the Kremlin to say that the United States did not want war, but he hoped that the Soviets would use their influence to persuade North Vietnam to not attack American warships.

[49] Herrick's report concluded with the statement the "entire action leaves many doubts" as he noted that no sailor aboard his ship had seen a torpedo boat nor had heard any gunfire beyond the guns of the Turner Joy.

"[52] Early on the morning of 04 August 1964, Johnson told several congressmen at a meeting that North Vietnam had just attacked an American patrol in the Gulf of Tonkin in international waters and promised retaliation.

[49] Admiral Sharp in turn applied strong pressure on Herrick to rewrite his report to "confirm absolutely" that his patrol had been just attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats.

[54] At a meeting of the National Security Council, Rusk pressed for a bombing raid, saying the second alleged attack was more serious of the two incidents and that it indicated that North Vietnam wanted war with the United States.

Johnson invited 18 senators and congressmen led by Mansfield to the White House to inform them he had ordered a bombing raid on North Vietnam and asked for their support for a resolution.

[59] The atmosphere of the meeting with Johnson saying that the American warplanes were on their way to bomb North Vietnam made it difficult for those present to oppose the president, out of the fear of appearing unpatriotic.

"[62] Within hours, President Johnson ordered the launching of retaliatory air strikes (Operation Pierce Arrow) on the bases of the North Vietnamese torpedo boats and announced, in a television address to the American public that same evening, that U.S. naval forces had been attacked.

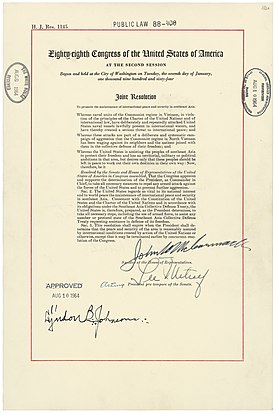

[62] On 05 August 1964, Johnson submitted the resolution to Congress, which if passed would give him the legal power to "take all necessary measures" and "prevent further aggression" as well as allowing him to decide when "peace and security" in Southeast Asia were attained.

[57] Despite his public claims of "aggression", Johnson in private believed that the second incident had not taken place, saying at a meeting in the Oval Office in his Texas twang: "Hell, those dumb stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish".

Johnson argued to Fulbright that the resolution was an election year stunt that would prove to the voters that he was really "tough on Communism" and thus dent the appeal of Goldwater by denying him of his main avenue of attack.

[67] The administration did not, however, disclose that the island raids, although separate from the mission of Maddox, had been part of a program of clandestine attacks on North Vietnamese installations called Operation Plan 34A.

[67] On 06 August 1964, Fulbright gave a speech on the Senate floor calling for the resolution to be passed as he accused North Vietnam of "aggression" and praised Johnson for his "great restraint...in response to the provocation of a small power".

J. Blair Seaborn, the Canadian diplomat who served as Canada's representative to the International Control Commission engaged in secret "shuttle diplomacy" carrying messages back and forth from Hanoi to Washington in an attempt to stop the escalation of the war.

[87] A memo co-written by "Mac" Bundy and McNamara in January 1965 stated "our present policy can lead only to a disastrous defeat" with the alternative being either "salvage what little can be saved" by withdrawing or to commit American forces to war.

[89] After a Viet Cong attack on the American air base at Pleiku in February 1965, Johnson called a meeting at the White House attended by his national security team plus Mansfield and McCormack to announce that "I've had enough of this" and that he had decided on a bombing campaign.

[95] At the same time, Johnson approved Westmoreland's request for "offensive defense" by allowing the Marines to patrol the countryside instead of just guarding the air base, committing the U.S. to a ground war.

[97] In June, Westmoreland reported "The South Vietnamese armed forces cannot stand up to this pressure without substantial U.S. combat troops on the ground" and stated that he needed 180, 000 men immediately, a request that was granted in July.