Bernoulli's principle

Bernoulli's principle is a key concept in fluid dynamics that relates pressure, density, speed and height.

Bernoulli's principle states that an increase in the speed of a parcel of fluid occurs simultaneously with a decrease in either the pressure or the height above a datum.

[1]: Ch.3 [2]: 156–164, § 3.5 The principle is named after the Swiss mathematician and physicist Daniel Bernoulli, who published it in his book Hydrodynamica in 1738.

This states that, in a steady flow, the sum of all forms of energy in a fluid is the same at all points that are free of viscous forces.

[6]: Example 3.5 and p.116 Bernoulli's principle can also be derived directly from Isaac Newton's second Law of Motion.

However, the principle can be applied to various types of flow within these bounds, resulting in various forms of Bernoulli's equation.

More advanced forms may be applied to compressible flows at higher Mach numbers.

Bernoulli performed his experiments on liquids, so his equation in its original form is valid only for incompressible flow.

For example, in the case of aircraft in flight, the change in height z is so small the ρgz term can be omitted.

"[1]: § 3.5 The simplified form of Bernoulli's equation can be summarized in the following memorable word equation:[1]: § 3.5 Every point in a steadily flowing fluid, regardless of the fluid speed at that point, has its own unique static pressure p and dynamic pressure q.

The significance of Bernoulli's principle can now be summarized as "total pressure is constant in any region free of viscous forces".

However, Bernoulli's principle importantly does not apply in the boundary layer such as in flow through long pipes.

The Bernoulli equation for unsteady potential flow is used in the theory of ocean surface waves and acoustics.

Here ∂φ/∂t denotes the partial derivative of the velocity potential φ with respect to time t, and v = |∇φ| is the flow speed.

The only exception is if the net heat transfer is zero, as in a complete thermodynamic cycle or in an individual isentropic (frictionless adiabatic) process, and even then this reversible process must be reversed, to restore the gas to the original pressure and specific volume, and thus density.

[15] It is possible to use the fundamental principles of physics to develop similar equations applicable to compressible fluids.

where: The most general form of the equation, suitable for use in thermodynamics in case of (quasi) steady flow, is:[2]: § 3.5 [17]: § 5 [18]: § 5.9

For steady inviscid adiabatic flow with no additional sources or sinks of energy, b is constant along any given streamline.

An exception to this rule is radiative shocks, which violate the assumptions leading to the Bernoulli equation, namely the lack of additional sinks or sources of energy.

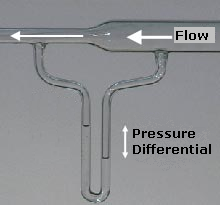

The simplest derivation is to first ignore gravity and consider constrictions and expansions in pipes that are otherwise straight, as seen in Venturi effect.

If the pressure decreases along the length of the pipe, dp is negative but the force resulting in flow is positive along the x axis.

[19] In the form of the work-energy theorem, stating that[20] Therefore, The system consists of the volume of fluid, initially between the cross-sections A1 and A2.

This is the head equation derived from Bernoulli's principle: The middle term, z, represents the potential energy of the fluid due to its elevation with respect to a reference plane.

In modern everyday life there are many observations that can be successfully explained by application of Bernoulli's principle, even though no real fluid is entirely inviscid,[22] and a small viscosity often has a large effect on the flow.

One of the most common erroneous explanations of aerodynamic lift asserts that the air must traverse the upper and lower surfaces of a wing in the same amount of time, implying that since the upper surface presents a longer path the air must be moving over the top of the wing faster than over the bottom.

Bernoulli's principle is then cited to conclude that the pressure on top of the wing must be lower than on the bottom.

[26][27] Equal transit time applies to the flow around a body generating no lift, but there is no physical principle that requires equal transit time in cases of bodies generating lift.

In fact, theory predicts – and experiments confirm – that the air traverses the top surface of a body experiencing lift in a shorter time than it traverses the bottom surface; the explanation based on equal transit time is false.

[33] One involves holding a piece of paper horizontally so that it droops downward and then blowing over the top of it.

[51][52][53] Other common classroom demonstrations, such as blowing between two suspended spheres, inflating a large bag, or suspending a ball in an airstream are sometimes explained in a similarly misleading manner by saying "faster moving air has lower pressure".