Charles's law

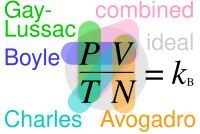

A modern statement of Charles's law is: When the pressure on a sample of a dry gas is held constant, the Kelvin temperature and the volume will be in direct proportion.

In two of a series of four essays presented between 2 and 30 October 1801,[2] John Dalton demonstrated by experiment that all the gases and vapours that he studied expanded by the same amount between two fixed points of temperature.

Dalton was the first to demonstrate that the law applied generally to all gases, and to the vapours of volatile liquids if the temperature was well above the boiling point.

[6] With measurements only at the two thermometric fixed points of water (0°C and 100°C), Gay-Lussac was unable to show that the equation relating volume to temperature was a linear function.

Unaware of the inaccuracies of mercury thermometers at the time, which were divided into equal portions between the fixed points, Dalton, after concluding in Essay II that in the case of vapours, “any elastic fluid expands nearly in a uniform manner into 1370 or 1380 parts by 180 degrees (Fahrenheit) of heat”, was unable to confirm it for gases.

This fact is related to a phenomenon which is exhibited by a great many bodies when passing from the liquid to the solid-state, but which is no longer sensible at temperatures a few degrees above that at which the transition occurs.

[3] The first mention of a temperature at which the volume of a gas might descend to zero was by William Thomson (later known as Lord Kelvin) in 1848:[7] This is what we might anticipate when we reflect that infinite cold must correspond to a finite number of degrees of the air-thermometer below zero; since if we push the strict principle of graduation, stated above, sufficiently far, we should arrive at a point corresponding to the volume of air being reduced to nothing, which would be marked as −273° of the scale (−100/.366, if .366 be the coefficient of expansion); and therefore −273° of the air-thermometer is a point which cannot be reached at any finite temperature, however low.