Tracheal intubation

Other methods of intubation involve surgery and include the cricothyrotomy (used almost exclusively in emergency circumstances) and the tracheotomy, used primarily in situations where a prolonged need for airway support is anticipated.

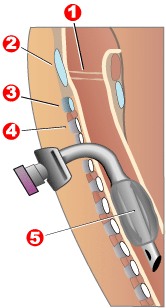

After the trachea has been intubated, a balloon cuff is typically inflated just above the far end of the tube to help secure it in place, to prevent leakage of respiratory gases, and to protect the tracheobronchial tree from receiving undesirable material such as stomach acid.

The tube is then secured to the face or neck and connected to a T-piece, anesthesia breathing circuit, bag valve mask device, or a mechanical ventilator.

It was not until the late 19th century, however, that advances in understanding of anatomy and physiology, as well an appreciation of the germ theory of disease, had improved the outcome of this operation to the point that it could be considered an acceptable treatment option.

Also at that time, advances in endoscopic instrumentation had improved to such a degree that direct laryngoscopy had become a viable means to secure the airway by the non-surgical orotracheal route.

Because of this, the potential for difficulty or complications due to the presence of unusual airway anatomy or other uncontrolled variables is carefully evaluated before undertaking tracheal intubation.

Tracheal intubation is indicated in a variety of situations when illness or a medical procedure prevents a person from maintaining a clear airway, breathing, and oxygenating the blood.

Tracheal intubation is often required to restore patency (the relative absence of blockage) of the airway and protect the tracheobronchial tree from pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents.

[1] Examples of such conditions include cervical spine injury, multiple rib fractures, severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), or near-drowning.

Due to the widespread availability of such devices, the technique of blind intubation[8] of the trachea is rarely practiced today, although it may still be useful in certain emergency situations, such as natural or man-made disasters.

The Miller blade, characterized by its straight, elongated shape with a curved tip, is frequently employed in patients with challenging airway anatomy, such as those with limited mouth opening or a high larynx.

Additionally, there exists a myriad of specialty blades with unique features, including mirrors for enhanced visualization and ports for oxygen administration, primarily utilized by anesthetists and otolaryngologists in operating room settings.

Most endotracheal tubes have an inflatable cuff to seal the tracheobronchial tree against leakage of respiratory gases and pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents, blood, secretions, and other fluids.

[36] Tracheal intubation in the emergency setting can be difficult with the fiberoptic bronchoscope due to blood, vomit, or secretions in the airway and poor patient cooperation.

[34] RSI traditionally involves preoxygenating the lungs with a tightly fitting oxygen mask, followed by the sequential administration of an intravenous sleep-inducing agent and a rapidly acting neuromuscular-blocking drug, such as rocuronium, succinylcholine, or cisatracurium besilate, before intubation of the trachea.

Another key feature of RSI is the application of manual 'cricoid pressure' to the cricoid cartilage, often referred to as the "Sellick maneuver", prior to instrumentation of the airway and intubation of the trachea.

[34] Named for British anesthetist Brian Arthur Sellick (1918–1996) who first described the procedure in 1961,[46] the goal of cricoid pressure is to minimize the possibility of regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents.

[47] The initial article by Sellick was based on a small sample size at a time when high tidal volumes, head-down positioning and barbiturate anesthesia were the rule.

[51] While both of these involve digital pressure to the anterior aspect (front) of the laryngeal apparatus, the purpose of the latter is to improve the view of the glottis during laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation, rather than to prevent regurgitation.

In the chronic setting, indications for tracheotomy include the need for long-term mechanical ventilation and removal of tracheal secretions (e.g., comatose patients, or extensive surgery involving the head and neck).

[79] Under certain emergency circumstances (e.g., severe head trauma or suspected cervical spine injury), it may be impossible to fully utilize these the physical examination and the various classification systems to predict the difficulty of tracheal intubation.

[82] Tracheal intubation is generally considered the best method for airway management under a wide variety of circumstances, as it provides the most reliable means of oxygenation and ventilation and the greatest degree of protection against regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration.

These are typically of short duration, such as sore throat, lacerations of the lips or gums or other structures within the upper airway, chipped, fractured or dislodged teeth, and nasal injury.

[39][40] Newer technologies such as flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy have fared better in reducing the incidence of some of these complications, though the most frequent cause of intubation trauma remains a lack of skill on the part of the laryngoscopist.

[84] Complications may also be severe and long-lasting or permanent, such as vocal cord damage, esophageal perforation and retropharyngeal abscess, bronchial intubation, or nerve injury.

They may even be immediately life-threatening, such as laryngospasm and negative pressure pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs), aspiration, unrecognized esophageal intubation, or accidental disconnection or dislodgement of the tracheal tube.

[2] Higher quality studies demonstrate favorable evidence for this shift, as they have shown no survival or neurological benefit with endotracheal intubation over supraglottic airway devices (Laryngeal mask or Combitube).

[113] In 1871, the German surgeon Friedrich Trendelenburg (1844–1924) published a paper describing the first successful elective human tracheotomy to be performed for the purpose of administration of general anesthesia.

[117] In 1858, French pediatrician Eugène Bouchut (1818–1891) developed a new technique for non-surgical orotracheal intubation to bypass laryngeal obstruction resulting from a diphtheria-related pseudomembrane.

[118] In 1880, Scottish surgeon William Macewen (1848–1924) reported on his use of orotracheal intubation as an alternative to tracheotomy to allow a patient with glottic edema to breathe, as well as in the setting of general anesthesia with chloroform.

1 - Vocal folds

2 - Thyroid cartilage

3 - Cricoid cartilage

4 - Tracheal rings

5 - Balloon cuff