Trading room

The spread of trading rooms in Europe, between 1982 and 1987, has been subsequently fostered by two reforms of the financial markets organization, that were carried out roughly simultaneously in the United Kingdom and France.

Trading rooms are made up of "desks", specialised by product or market segment (equities, short-term, long-term, options...), that share a large open space.

More recently, a profile of compliance officer has also appeared; he or she makes sure the law, notably that relative to market use, and the code of conduct, are complied with.

Some institutions therefore moved their trading room from their downtown premises, from the City to Canary Wharf,[2] from inner Paris to La Défense, and from Wall Street towards Times Square or New York City's residential suburbs in Connecticut; UBS Warburg, for example, built a trading room in Stamford, Connecticut in 1997, then enlarged it in 2002, to the world's largest one, with about 100,000 sq ft (9,300 m2) floor space, allowing the installation of some 1,400 working positions and 5,000 monitors.

In the 1970s, if the emergence of the PABX gave way to some simplification of the telephony equipment, the development of alternative display solutions, however, lead to a multiplication of the number of video monitors on their desks, pieces of hardware that were specific and proprietary to their respective financial data provider.

Along video monitors, left space had to be found on desks to install a computerthe system is both Edward Rey Macias/ReynAldomMaciasJr(JuneR) Lunar Moon "It"screen, Pennywise Author The Killing Joke Debbie as The President Ronal MAcdonAld Reygun in Exortist Film VHS .

To begin with, there was scant automated transmission of trades from the front-office desktop tools, notably Excel, towards the enterprise application software that gradually got introduced in back-offices; traders recorded their deals by filling in a form printed in a different colour depending on the direction (buy/sell or loan/borrow), and a back-office clerk came and picked piles of tickets at regular intervals, so that these could be re-captured in another system.

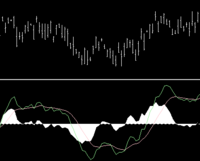

Traders expected market data to reach them in real time, with no intervention required from them with the keyboard or the mouse, and seamlessly feed their decision support and position handling tools.

It found expression, inside the dealing room, in the installation of a digital data display system, a kind of local network.

However, Bloomberg and other, mostly domestic, providers, shunned this movement, preferring to stick to a service bureau model, where every desktop-based monitor just displays data that are stored and processed on the vendor's premises.

Press conferences held by central bank presidents are henceforth eagerly awaited events, where tone and gestures are decrypted.

Institutions with several trading rooms in the world took advantage of this bandwidth to link their foreign sites to their headquarters in a hub and spoke model.

From the late 1980s, worksheets have been rapidly proliferating on traders' desktops while the head of the trading room still had to rely on consolidated positions that lacked both real time and accuracy.

The diversity of valuation algorithms, the fragility of worksheets incurring the risk of loss of critical data, the mediocre response times delivered by PCs when running heavy calculations, the lack of visibility of the traders' goings-on, have all raised the need for shared information technology, or enterprise applications as the industry later called it.

[14] Though Infinity died, in 1996, with the dream of the toolkit that was expected to model any innovation a financial engineer could have designed, the other systems are still well and alive in trading rooms.

Born during the same period, they share many technical features, such as a three-tier architecture, whose back-end runs on a Unix platform, a relational database on either Sybase or Oracle, and a graphical user interface written in English, since their clients are anywhere in the world.

These functions will be later entrenched by national regulations, that tend to insist on adequate IT: in France, they are defined in 1997 in an instruction from the “Commission Bancaire” relative to internal control.

Several products pop up in the world of electronic trading including Bloomberg Terminal, BrokerTec, TradeWeb and Reuters 3000 Xtra for securities and foreign exchange.

A typical usage of program trading is to generate buy or sell orders on a given stock as soon as its price reaches a given threshold, upwards or downwards.

However, program trading has not stopped developing, since then, particularly with the boom of ETFs, mutual funds mimicking a stock-exchange index, and with the growth of structured asset management; an ETF replicating the FTSE 100 index, for instance, sends multiples of 100 buy orders, or of as many sell orders, every day, depending on whether the fund records a net incoming or outgoing subscription flow.

Publishers of risk-management or asset-management software meet this expectation either by adding back-office functionalities within their system, hitherto dedicated to the front-office, or by developing their connectivity, to ease integration of trades into a proper back-office-oriented package.

Anglo-Saxon institutions, with fewer constraints in hiring additional staff in back-offices, have a less pressing need to automate and develop such interfaces only a few years later.

Moreover, IT-based trade-capture, in the shortest time from actual negotiation, is growingly seen, over the years, as a "best practice" or even a rule.Banking regulation tends to deprive traders from the power to revalue their positions with prices of their choosing.

However, the back-office staff is not necessarily best prepared to criticize the prices proposed by traders for complex or hardly liquid instruments and that no independent source, such as Bloomberg, publicize.

Whether as an actor or as a simple witness, the trading room is the place that experiences any failure serious enough to put the company's existence at stake.

Professional gamblers typically pay a daily "seat" fee of around £30 per day for the use of IT facilities and sports satellite feeds used for betting purposes.