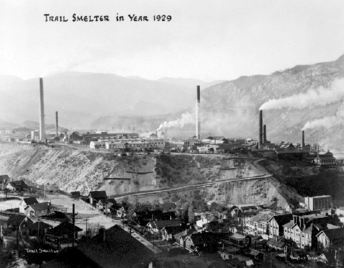

Trail Smelter dispute

[2] Prior to building the smelter, agents for Heinze signed a contract guaranteeing 75,000 tons of ore would be provided by Rossland's LeRoi Mining Company.

"[6] On the other hand, local farmers complained about the effects of the toxic smoke on their crops, which eventually led to arbitration with Cominco between 1917 and 1924, and resulted to the assessment $600,000 in fines being levied against the defendant.

The farmers and landowners in Washington who had a mutual concern for the smoke drifting from the smelter, formed the Citizens' Protective Association (CPA) when their direct complaints to Cominco were not addressed.

[1] Both governments were initially involved in the foundation of the International Joint Commission (IJC) in 1909, which was later responsible for investigating and then recommending a settlement for the alleged damages in the Trail case.

This included the Canada's National Research Council (NRC) and the American Smelting and Refining Company, which each contributed scientific experts to assess the damages from the smelter's smoke.

[1] A growing concern in 1925 was the smoke drifting from the smelter across the border into Washington, allegedly causing damages to crops and forests.

Complaints included: sulphur dioxide gases in the form of some smoke generated from the smelter was directed into the Columbia River Valley by prevailing winds, scorching crops and accelerating forest loss.

[4] After the complaints in 1925 regarding crop and forest destruction as a result of smoke from the smelter, Cominco accepted responsibility and offered to compensate the farmers who were affected.

[1] Cominco also proposed installing fume-controlling technologies to limit future damage and reduce the emissions of sulphur dioxide.

The company had initially raised smokestacks to four hundred feet in an effort to increase the dispersion of pollutants; however, this had resulted in prevailing winds moving the noxious fumes downwind to the inhabitants of the Columbia River Valley, thereby making the situation worse.

[1] The compensation was far less than the plaintiffs had expected and the IJC settlement was eventually rejected under the pressure of Washington State's congressional delegation.

The arbitration case was originally between the farmers in the affected area and Cominco; however, what started off as the smelter versus agriculturalists evolved when regional and federal agents became involved, resulting in the dispute becoming an international issue.

[1] The United States had conducted experiments that suggested sulphur soaked into the soil; however, the findings had limited standing in the arbitration because the data was from the early 1930s before the smelter implemented chemical recovery methods.

[1][5] The consequences of the arbitration came in two parts; one being economic compensation for the local farmers of Stevens County, Washington and two effecting laws for transboundary air pollution issues.

For the better part of twenty years, the company fought every attempt to impose any sort of regulatory regime aimed at production levels.

The American inter-state law precedent caused a stir again in 2003 when the Colville Confederated Tribes launched a complaint against Cominco for polluting Lake Roosevelt.

Douglas Horswill, Senior Vice President for Teck Resources, stated that "in the U.S. legal process...Teck COMINCO would not be able to use the fact that it was operating with valid permits in its defence [because it is a Canadian company], whereas a U.S. company could";[15] Horswill's media statement reflects the tensions created by formulating an international law based on American inter-state practices.

The legacy of this decision includes the eventual creation of regulatory regimes to prevent environmental degradation, which allow nations to put states in charge of taking positive steps to control pollution.