Whale oil

Its properties and applications differ from those of detergentized whale oil, and it was sold for a higher price.

There is a misconception that commercial development of the petroleum industry and vegetable oils saved whales from extinction.

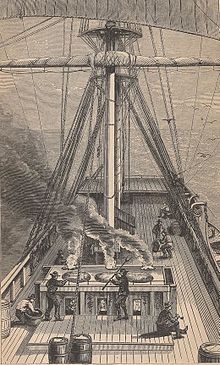

On longer deep-sea whaling expeditions, the trying-out was done aboard the ship in a furnace known as a trywork and the carcass was then discarded into the water.

[18] Cheaper alternatives to whale oil existed, but were inferior in performance and cleanliness of burn.

[19][citation needed] Due to dwindling whale populations causing higher voyage costs, as well as taxation, the market changed rapidly in the 1860s after the discovery of mineral oils and expansion of chemical refineries to produce kerosene and lubricants.

[26] Burning fluid and camphine were the dominant replacements for whale oil until the arrival of kerosene.

[28] After the invention of hydrogenation in the early 20th century, whale oil was used to make margarine,[10] a practice that has since been discontinued.

Until the invention of hydrogenation, it was used only in industrial-grade cleansers, because its foul smell and tendency to discolor made it unsuitable for cosmetic soap.

[11] Whale oil was widely used in the First World War as a preventive measure against trench foot.

[33] John R. Jewitt, an Englishman who wrote a memoir about his years as a captive of the Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka), an Indigenous Pacific Northwest people on the British Columbia Coast, from 1802 to 1805, claimed whale oil was a condiment with every dish, even strawberries.

Friedrich Ratzel in The History of Mankind (1896), when discussing food materials in Oceania, quoted Captain James Cook's comment in relation to the Māori people: "No Greenlander was ever so sharp set upon train-oil as our friends here, they greedily swallowed the stinking droppings when we were boiling down the fat of dog-fish.