History of philosophical pessimism

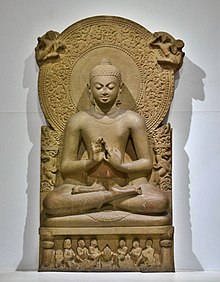

Notable early expressions of pessimistic thought can be found in the works of ancient philosophers such as Hegesias of Cyrene and in the Indian texts of Buddhism.

In addition to affirming the intrinsically evil character of the world, the Gnostic conceives it as hermetically sealed, surrounded by "outer darkness", by a "great sea" or by an "iron wall" identified with the firmament.

[17] Those whose higher part of the soul has remained extinct, or who are devoid of it, that is to say, all the individuals whom the Gnostics call hylics (the majority of human beings and all animals), are condemned to destruction or to wander in this world, undergoing the terrifying cycle of reincarnations.

Khayyam's early loss of his father and the subsequent hardships he experienced contributed to his pessimism, as did his awareness of the decline of intellectual and scientific achievements in the Islamic world at the time.

[27]: 230 Jennifer A. Herdt argues that Gracian held that "what the world values is deceptive simply because it appears solid and lasting but is in fact impermanent and transitory.

"[27]: 230 Arthur Schopenhauer engaged extensively with Gracián's works and considered El Criticón "Absolutely unique ... a book made for constant use ... a companion for life ... [for] those who wish to prosper in the great world".

He is noted for publishing the Pensées, a pessimistic series of aphorisms with the intention to highlight the misery of the human condition and turn people towards the salvation of the Catholic Church and God.

Pascal promotes in this perspective a reflexive form of pessimism, linking greatness and misery, where the disconsideration of oneself and the recognition of our impotence raise us above ourselves, making us renounce at the same time the vain search for happiness.

[39] Voltaire was the first European to be labeled as a pessimist by his critics, in response to the publication and international success of his 1759 satirical novel Candide;[40]: 9 a treatise against Leibniz's theistic optimism, refuting his affirmation that "we live in the best of all possible worlds.

The human soul (and likewise all living beings) always essentially desires, and focuses solely (though in many different forms), on pleasure, or happiness, which, if you think about it carefully, is the same thing.

To respond to this growing criticism, a group of philosophers greatly influenced by Schopenhauer (indeed, some even being his personal acquaintances) developed their own brand of pessimism, each in their own unique way.

[68] Julius Bahnsen would reshape the understanding of pessimism overall,[1]: 231 while Philipp Mainländer set out to reinterpret and elucidate the nature of the will, by presenting it as a self-mortifying will-to-death.

Frances Power Cobbe, in her 1877 essay, critiqued Schopenhauer's misogyny but argued that the rise of pessimism reflected growing empathy—a sign of societal progress.

Thus, the main theme of Bahnsen's philosophy became his own idea of the Realdialektik, according to which there is no synthesis between two opposing forces, with the opposition resulting only in negation and the consequent destruction of contradicting aspects.

[1]: 267 Though he insists that humor does not necessarily extricate us from our tragic situation, he does believe that it allows us to momentarily detach or abstract ourselves from it (in a similar way to Schopenhauer's view on aesthetic contemplation through art).

It ultimately however offers no enduring remedies, no reliable methods to escape from the suffering and moral dilemmas of life; its only power is to lighten the load and to prepare us for even more to come.

In this perspective, he constructs a remarkable anthropomorphic creation mythology in which God appears as a perfectly free and omnipotent individual, but who discovers with horror his own limitation in the very fact of his existence, which he cannot directly abolish, being the primary condition of all his powers.

Von Hartmann explains that there are three fundamental illusions about the value of life that must be overcome before humanity can achieve what he calls absolute painlessness, nothingness, or Nirvana.

[40]: 178 He believed that the task of the philosopher was to wield this pessimism like a hammer, to first attack the basis of old moralities and beliefs and then to "make oneself a new pair of wings", i.e. to re-evaluate all values and create new ones.

[40]: 181 A key feature of this Dionysian pessimism was "saying yes" to the changing nature of the world, which entailed embracing destruction and suffering joyfully, forever (hence the ideas of amor fati and eternal recurrence).

[40]: 199 The pessimism of many of the thinkers of the Victorian era has been attributed to a reaction against the "benignly progressive" views of the Age of Enlightenment, which were often expressed by the members of the Romantic movement.

[88] Several British writers of the time have been noted for the pervasive pessimism of their works, including Matthew Arnold, Edward FitzGerald, James Thomson, Algernon Charles Swinburne, Ernest Dowson, A. E. Housman, Thomas Hardy,[89] Christina Rossetti,[90] and Amy Levy;[91] the pessimistic themes particularly deal with love, fatalism, and religious doubt.

Camus believed that people often escape facing the absurd through "eluding" (l'esquive), a "trickery" for "those who live not for life itself but some great idea that will transcend it, refine it, give it a meaning, and betray it".

Camus illustrated his response to the condition of the absurd by using the Greek mythic character of Sisyphus, who was condemned by the gods to push a boulder up a hill for eternity, only for it to roll down again when it reached the top.

"[95]: 123 Peter Wessel Zapffe argued that evolution bestowed humans with a surplus of consciousness which allowed them to contemplate their place in the cosmos and yearn for justice and meaning together with freedom from suffering and death, while simultaneously being aware that nature or reality itself cannot satisfy those deep longings and spiritual demands.

[96] For Zapffe, this was a tragic byproduct of evolution: humans' full apprehension of their ill-fated and vulnerable situation in the universe would, according to him, cause them to fall into a state of "cosmic panic" or existential terror.

[3]: 158–159 According to TMT, such existential angst is born from the juxtaposition of human beings' awareness of themselves as merely transient animals groping to survive in a meaningless universe, destined only to die and decay.

Lacking interest in traditional philosophical systems and jargon, he rejects very early abstract speculation in favor of personal reflection and passionate lyricism.

"[102] William H. Gass described Cioran's The Temptation to Exist as "a philosophical romance on the modern themes of alienation, absurdity, boredom, futility, decay, the tyranny of history, the vulgarities of change, awareness as agony, reason as disease".

[111]: 82–83 Benatar's suggested strategy for dealing with the above-mentioned facts is through what he calls "pragmatic pessimism", which involves engaging in activities that create terrestrial meaning (for oneself, other humans, and other animals).